Print Version (PDF)

Seeding Food Justice: Community-Led Practices for Local Government Policy in Dougherty County, Georgia

In March 2015, Dougherty County, Georgia was selected as one of eight Communities of Opportunity (COOs) in the country that have significant potential to strengthen ties between small- and medium-sized farmers and residents with limited food access.1 Working with the Growing Food Connections (GFC) project team, county stakeholders have since established a steering committee that has charted a vision for the future of Dougherty’s food system.2

This brief, which draws on interviews with Dougherty County stakeholders and secondary data sources, provides information about local government policy opportunities and challenges in the food system to inform the work of the GFC steering committee and stakeholders in Dougherty County.

Background

This community garden in Dougherty County is a joint partnership between two churches and is a space where parishioners grow food that is free for the taking. Image Source: American Farmland Trust

In the City of Albany and Dougherty County, Georgia, community efforts to establish farmers’ markets, farm-to-school programs, and a regional food hub are drawing attention to the realities that: small farmers and low-income residents are marginalized by the current food system; African Americans are agents of change in the community food system; and regional approaches to food systems planning that foster connections between urban and rural areas are essential. Stronger public-policy support, especially from local governments, can amplify community efforts to promote agricultural viability and food security and address racial and economic disparities.

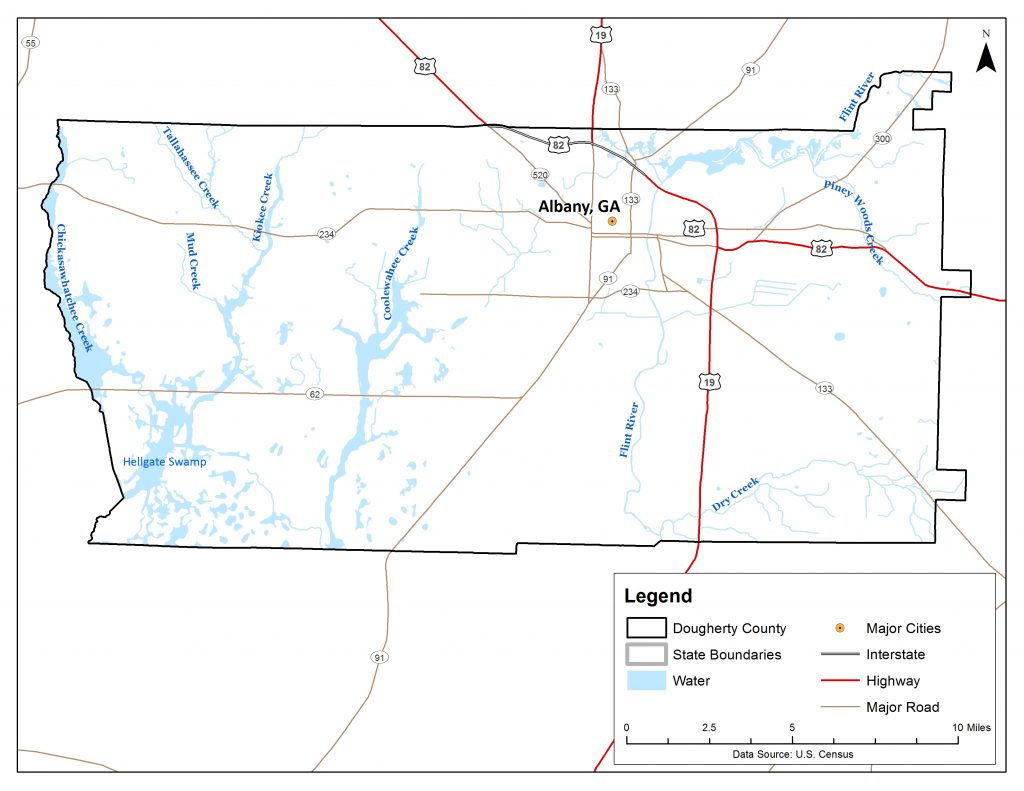

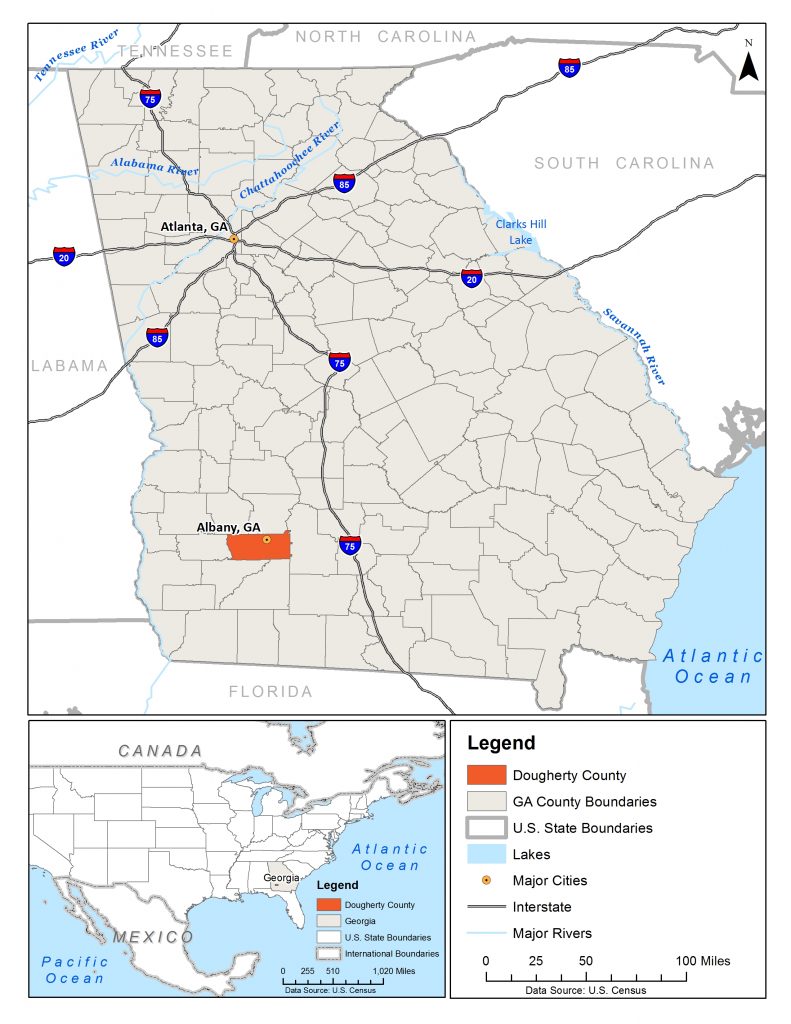

Dougherty County is the physical and economic center of the 14-county Southwest Georgia region (see figure 1).3 Although the least populated and poorest region in the state, Southwest Georgia has an abundance of natural resources including prime farmland, forested areas, and wetlands. The area sits on top of one of the most productive water recharge areas in the world, the Floridian aquifer. There are also many important surface water resources in the county, including Lake Seminole and the Flint and Chattahoochee Rivers. Dougherty County is the largest county in the Southwest Georgia region, with a total population of nearly 94,000 residents and a land area of about 329 square miles.4 The county’s character is a blend of urban and rural, with a city surrounded by large plantations, cypress swamps and quail reserves. The majority of the county’s residents live in the City of Albany (82 percent).4 The remaining county residents live in unincorporated areas outside the city that are less densely populated but are home to the majority of the county’s agriculture and forestry activities.5 The majority of county residents are Black or African American (68 percent), with the remaining residents largely identifying as White (27 percent).4

Historically, Albany and Dougherty County gained prominence as an agricultural trade center for commodity crops like cotton and pecan. The county, much like the surrounding region, was dominated by cotton plantation agriculture in the nineteenth century. Albany’s strategic location on the Flint River led to its prominence as a market center for shipment of goods. This economic prosperity also relied on the unpaid labor of African Americans as enslaved persons, sharecroppers, and tenant farmers. Pecan farming was introduced in the region in the late 1800s, and by 1905, several thousand trees were in cultivation in the county. Georgia quickly became the leading producer of pecans in the country, with much of the business centered around the Albany area. By the 1920s, with the decline of cotton production caused by the boll weevil, pecans became the area’s leading cash crop. In 1922, the Albany District Pecan Growers’ Exchange opened its factory building and warehouse, and pecans became a major Albany product, leading to the city’s informal claim as the pecan capital of the world.6 Over the course of the twentieth century, as technological advancements changed the nature of agriculture, the county sought to diversify its industrial base. Albany and the surrounding area garnered national attention during the civil rights era of the 1960s, as the city was the focus of a major campaign to challenge racial segregation and discrimination in the South.7

Dougherty County is located in Southwest Georgia. Image Source: UB Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab

Today, Albany and Dougherty County is the commercial, educational, and cultural hub of Southwest Georgia. Major industries in the county include manufacturing, logistics and distribution, health care, professional services, defense, and retail.8 Three institutions of higher education, Albany State University, Albany Technical College, and Troy University, are located in the county. The county attracts visitors through its numerous recreational and historic sites, including the Albany Civil Rights Institute, Albany Museum of Art, and Flint RiverQuarium. With a strong cluster of advanced industries, anchor institutions, and regional assets, Dougherty County is poised to become a regional leader. Not surprisingly, local government officials have identified economic development, downtown revitalization, and tourism as top public-policy priorities. The county’s rich legacies of agriculture and community organizing for social justice extend to the present and intersect in ways that offer promising opportunities to strengthen the county through its food system.9

Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities

Agriculture represents a significant portion of Dougherty County’s economy and contributes to residents’ sense of place. Agriculture drives both the rural economy, as well as much of the city’s commercial and industrial activities. The City of Albany is the regional economic hub for agri-businesses and some of its major employers are food processors. Food products made in Albany include: Kroger brand products by Tara Foods; Combos and goodness knows by Mars Chocolate North America; pecans by Sunnyland Farms; and beer, malt beverages and ciders by MillerCoors.10 Agriculture also represents the largest land use in Dougherty County, comprising about 60 percent of the county’s total land area.5 Land used for farming, livestock production, commercial timber or pulpwood harvesting is included in this category. Most agricultural land is located in the unincorporated areas of the county, and much of this land is categorized by large land holdings.5 Some agricultural land is located within or adjacent to the city limits and consists of actively managed and productive pecan orchards. The county also has over ten privately owned plantations exclusive to hunting and event services that attract visitors from all over the world.5

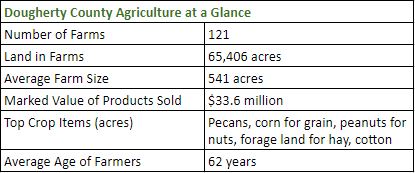

The top crop items in the county are commodities, including pecans, corns, peanuts, and cotton.11 The county ranked number two in the state and number five in the country for acreage dedicated to pecans.11 However, there is relatively little production of fruits and vegetables. For example, the county ranked number 140 (out of 159) in the state for value of sales in the crop group vegetables, melons, potatoes, and sweet potatoes.11 Local stakeholders noted that the county’s small farms produce a wide range of agricultural products, including watermelons, satsumas, honey, and vegetables.2 The county also has several poultry houses and a handful of goat and sheep operations.5

While the county’s agricultural sector is dominated by large plantations and commodity crops, the local picture of agriculture is much more complex. The average farm size in the county is 541 acres, but 71 percent of farms are less than 180 acres in size, while 13 percent of county farms are greater than 1,000 acres in size.11 While on average each farm in the county earned $277,561 in 2012, 106 farms earned less than $50,000—with 68 of these farms earning less than $1,000.11 Yet 15 farms earned $500,000 or more in the same year.11 The massive profits generated by large farms conceals the reality that the majority of farms in the county are struggling to remain viable. Additionally, with nearly 50 percent of principal farm operators in the county having a primary occupation other than farming, it is unclear if farming is a hobby for some people or if they would like to scale up their farm business, but face challenges to doing so.11

Challenges

Respondents identified making a profit as the biggest challenge facing farmers in Dougherty County, particularly small farmers and vegetable farmers. According to community advocates, there are few incentives for local farmers to grow food crops, as financial assistance is more readily available for growing commodities.12 A farming and agriculture representative also cited the intensive labor required for vegetable farming as a deterrent for scaling up food production in particular, and for attracting younger people to the profession overall.13 This labor market challenge is important to address given that the average age of farmers in the county is 62 years old, which is higher than the national average of 58 years.11

Farmers and farming advocates see connections to local markets as key to preserving the small-scale farming activity that exists in Dougherty County.14 However, there are limited food processing businesses, vegetable packing warehouses, aggregation facilities, and distribution channels in the county. Farmers also struggle to find local markets where they can sell their produce.15 There are relatively few farmers’ markets in the county and efforts to establish farm-to-school programs are constrained by inadequate food infrastructure.15 Even with more sufficient infrastructure, farmers need to obtain certification to ensure good agricultural practices and food safety to supply to institutional markets.16

Land use patterns may also impede efforts to scale up the county’s food production. Across the county, farmland is under threat from development pressures, challenging the ability of both established and beginning farmers to access available, suitable, and affordable land.5 While the county has high quality soils, scattered development is breaking up farmland into smaller and smaller parcels, reducing its commercial viability.5 Farmland loss has a distinct meaning and history for Black farmers, who make up about one-fifth of farmers in the county—a relatively significant share given that Black farmers make up only four percent of farmers in the state overall.11 Black farmers experienced racial discrimination in accessing land and other resources, resulting in decades of

sustained land loss.17, 18

In recent years, Southwest Georgia has experienced severe droughts, causing farmers to rely more heavily on irrigation.19 However, there are increasing restrictions on the water supply. In 2012, the Georgia Environmental Protection Division announced a suspension of new applications for agricultural water withdrawal permits in a 24-county area of South Georgia, including Dougherty County.20 The suspension also applies to requests to modify existing permits to increase withdrawals or increase the number of irrigated acres.20 These restrictions pose potential barriers to the expansion of large-scale agriculture in Dougherty County. This is not as much of an issue for small farms, as residents are allowed to use up to 70 gallons per minute without a permit.2 Several respondents also expressed concerns regarding the ongoing tri-state water dispute between Alabama, Florida, and Georgia over rights to the Floridan Aquifer.12

Opportunities

A recent development project in Albany has generated excitement around agri-business as a strategy for economic development and urban revitalization. Pretoria Fields is a new farmhouse microbrewery in downtown Albany, representing one of only a few farm breweries in the county and the first handcrafted beer brewery in the city.21 The $6 million project is a spin-off business of a local farm and features a brewery and beer garden in an area of downtown that has been targeted for revitalization efforts.22 The city contributed $1.25 million from a revolving loan fund designed to attract private development downtown to make the project happen.23 The money will be repaid to the loan fund over the next 15 years through the brewery’s property taxes.23

Community advocates see missed opportunities to connect small farmers to underserved areas, a connection that would provide farmers with a consumer base and underserved areas with healthy food and local jobs.24 A major focus of Southwest Georgia Project, a community organization, has been connecting small farmers to local market opportunities. Founded in 1961, Southwest Georgia aims to educate, engage, and empower residents in the region through advocacy and community organizing around human rights and social justice issues, including agriculture and food.25 Southwest Georgia Project has established several direct to consumer farmers’ markets that accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits in three counties and facilitated farm-to-school initiatives in several school districts in the region.14 The organization is currently planning a regional food hub with aggregation, processing, and distribution facilities in Albany.16 With the presence of large, anchor institutions in Dougherty County including the school district, regional hospital, and several universities, there is great potential for farm-to-institution programs and local procurement policies to connect local farmers to local markets.

There are strong community organizations in the region that advocate for small farmers and provide training and business development assistance, including the Southwest Georgia Project, Federation of Southern Cooperatives, and Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative. Many of these organizations focus on outreach and assistance to Black and other “socially disadvantaged” farmers to increase participation in federal programs, as well as connect farmers with opportunities to sell their produce. USDA “2501 program” grants help support this work.24 The Southwest Georgia Project hosts workshops for small farmers across the region on topics of estate and succession planning, whole farm insurance, and other crop insurance, and emerging market opportunities. In 2017, the organization hosted their second annual “Food, Ag and Equity Conference” in Albany to connect consumers with local growers and to empower local producers.26

Food Security: Challenges and Opportunities

Farmer Alfred Greene at his pasture horse boarding farm in Albany, GA. He is standing in front of his new high tunnel where watermelons will soon be growing. Image Source: American Farmland Trust

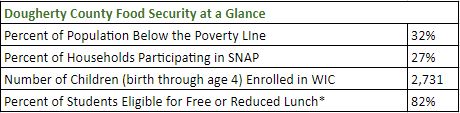

Many residents in Dougherty County are struggling to gain access to healthful, affordable and culturally acceptable foods. Dougherty County has the highest rate of food insecurity of all 159 counties in Georgia and one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the nation.27 Nearly 27 percent of county residents—25,500 residents—are food insecure and lack adequate access to healthful, affordable and culturally acceptable foods.27 Respondents reported that low-income, African American residents in both urban and rural areas of the county are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity.16 Children are also vulnerable to food insecurity—it is estimated that 28 percent of children under age 18 in the county are food insecure.28

Safety net programs provide support to food-insecure households in Dougherty County. About 27 percent of households in the county receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.4 Unlike many safety net programs, SNAP eligibility is not limited to families with children or to the elderly, making it an important source of support. About 2,400 children (ages birth through 4) in the county are enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) that provides nutrition education and supplemental foods to low-income pregnant and postpartum women and infants and children up to age five who are found to be at nutritional risk.29

Challenges

Poverty and unemployment are major drivers of food insecurity in Dougherty County. Half of households in the county earn less than $33,600 a year, compared to the median household income of $51,000 for the state and $55,300 for the nation.4 Nearly a third of county residents live below the poverty line.4 In 2016, the annual average unemployment rate for the county was 6.9 percent, higher than the unemployment rate for the state (5.4 percent) and the nation (4.9 percent) during the same year.30 These challenges disproportionately impact the county’s African Americans residents. The poverty rate for Black residents (37 percent) is more than double the poverty rate for White residents (16 percent).4 The median household income for White households in the county ($52,000) is nearly double the median household income for Black households in the county ($28,000).4

Several grocery stores in the county have closed in recent years, reducing the availability and accessibility of healthy foods for the county’s most vulnerable residents.31 Respondents identified a concentration of grocery stores on the west side of Albany, and an absence of grocery stores on the city’s east and south sides, where there is a predominance of convenience stores with processed foods.32 Local government has made efforts to attract grocery stores to underserved neighborhoods, but negative perceptions of high crime and low spending power discourage private sector investment.32 Additionally, there are limited alternative sources of fresh foods such as farmers’ markets and community-supported agriculture in Dougherty County.13

Limited public transit service and poor walking conditions in various areas of the county create additional barriers to healthy food accessibility for residents. Nearly 13 percent of households in the county do not have access to a car; nearly all these households live in the City of Albany.4 While Albany Transit System operates a fixed-route bus system and paratransit services, respondents report that transit service is often infrequent and inconvenient.31 Sidewalk infrastructure is minimal or non-existent in many residential areas of the county, with sidewalks primarily located in downtown Albany.

Some respondents noted that even with increased access to healthier food options, low incomes might limit purchase and consumption of fresh foods, which are often more expensive than processed and packaged foods.13 Similarly, some respondents emphasized the need for nutrition education or food preparation classes to increase knowledge of healthy food practices.33

Opportunities

Dougherty County has a strong charitable food assistance system. At the center of this network is Second Harvest of South Georgia, a regional food bank that links people in need to food and nutrition resources in the community through their own services and those of their partner agencies. The food bank operates a warehouse in Albany where it distributes food to partner agencies who directly serve people that are otherwise unable to provide adequate food for themselves or their families.34 Some churches and pantries also distribute food and there is an active Meals on Wheels program in the county.2

Dougherty County School System is a key advocate for reducing child hunger and food insecurity in the county. Since 2013, all students in the county school district receive a free breakfast and lunch, regardless of household income, through the district’s participation in the federal Community Eligibility Provision (CEP).35 The school district has also incorporated a “third meal” in several schools to provide an after-school supper to students.24 In recent years, farm-to-school initiatives have introduced new vegetables and planted school gardens at several schools in the county.24 School district representatives have also expressed interest in local procurement policies that would enable the district to purchase more locally grown food.24

Grassroots efforts to establish farmers’ markets offer community-based models for increasing connections between farmers and underserved consumers, for increased knowledge of and access to healthy foods. In 2011, Southwest Georgia Project reached out to local government officials for assistance with establishing a farmers’ market in downtown Albany.16 The organization identified a vacant parking deck that would provide ample space and shade to vendors and visitors. However, county officials placed a number of restrictions on the kinds of products that could be sold at the market.16 For instance, vendors could not sell bread or value-added products, which made it challenging to get the buy-in of vendors.16 The market only lasted for a couple of years, given the limitations on what products could be sold and limited ongoing financial support.16 Community members cite the recently created Tift Park Community Market as offering a popular, accessible venue to purchase produce from local farmers.14 The Tift Market is held in a public park and features a variety of products, many of which are not food related, but help draw a large number of visitors to the market. Some respondents observed that the market tends to attract a wealthier segment of the community, and not so much the individuals who could really benefit from being able to buy fresh produce.16

Local Government Public-Policy Environment

Warehouse at the Second Harvest of South Georgia food bank in Albany, GA. Image Source: American Farmland Trust

There is strong community support for food systems issues, but several factors hinder local government engagement in food systems planning. Respondents identified a limited awareness of and interest in food systems issues within the local government. When local governments do address food, they tend to focus on agricultural zoning and land use regulations. While economic development is a primary public policy concern, there is little recognition of the role that food systems could play in promoting economic development as documented nationally.36 Deep-rooted racial divisions may also hinder communication and collaboration between a predominantly White public sector and Black-led community organizations that are leading solutions to strengthen community food systems. However, there are a number of existing governance structures and local government priorities that could facilitate greater local government engagement in food systems planning in Dougherty County.

Intergovernmental Coordination

Dougherty County has two general purpose governments: the county government and the municipal government in the City of Albany.37 Through a cooperative agreement, the city and county governments operate joint departments, including a joint planning department.38 This collaborative structure offers opportunities for tying together the priorities and investments of the urban core to the outlying rural areas. The county also has six special purpose governments: five special districts and one independent school district, the Dougherty County School System.37 Intergovernmental coordination between city and county governments, and with civic organizations, could lay the stage for innovative and equitable food policy in Dougherty County.

Community-Led Food Projects

Community organizations have led or played a significant role in developing programs and projects to strengthen small- and medium-sized agriculture and improve food access for underserved residents in Dougherty County. Listed below are a few recent actions of potential interest to local planners and policymakers:

East Baker Commercial Kitchen (2005): Established in 2005, East Baker Kitchen is a commercial kitchen located in a former elementary school in Baker County (adjacent to Dougherty County). The commercial kitchen features a state-of-the-art cooking facility and serves as a hub for food entrepreneurs and community members to sell locally grown fruit, vegetables, and value-added products. The enterprise provides micro-loans and access to equipment that is often out of reach for small food businesses.

Dougherty County Farm-to-School Program (2013-Present): With funding from a 2013 USDA Farm to School Program implementation grant, Southwest Georgia Project launched a farm-to-school program in Dougherty County to increase the supply of fresh, locally grown food in schools. Southwest Georgia Project worked closely with the Dougherty County School System (DCSS)’s School Nutrition Services department to implement the program. The program has enabled several schools in the county to serve local foods, plant school gardens, and invite farmers to talk to students. DCSS’s farm-to-school goal is to purchase 20 percent of the produce served from farms within 100 miles of the county. A major barrier to program expansion is the absence of processing infrastructure for small and mid-sized farmers in the region. Despite this challenge, the school district and community partners continue to pursue opportunities to support local farmers and the local food economy while simultaneously promoting healthy eating among students. Community advocates envision the farm-to-school program as a key component of a regional food system anchored by small farmers and food entrepreneurs.

Albany Regional Food Hub Project (2015-Present): Southwest Georgia Project is currently planning a regional food hub in the City of Albany for the development of local food infrastructure. The food hub will provide aggregation, processing, and distribution facilities for small farmers in Dougherty County and surrounding counties to clean, process, package, and ship their crops for consumption. The venue will allow residents to buy fresh produce directly from local farmers, increasing healthy food options in Albany and fostering connections between farmers and consumers. The food hub will also create jobs, within the facility but also on farms, as the provision of a large market and processing equipment will offer incentives to increasing farming activity. A food hub would support and scale up other local efforts to connect farmers and consumers, including the DCSS farm-to-school program, farmers’ markets in downtown Albany, and outreach and technical assistance to minority farmers. The project could also employ out of work persons for processing labor, create value-added businesses, serve as a training site for ongoing certification and business management courses, and provide fresh produce in underserved areas. The organization’s efforts received a major boost in 2015, with the donation of a former Winn-Dixie grocery store building in Albany. The 47,000-square-foot building, valued at $2.35 million, sits on 3.9 acres of land. Southwest Georgia Project anticipates the food hub could serve at least 100 farmers from Dougherty County and surrounding counties for use as a processing facility and market to sell their produce. The food hub will also include retail vending and community meeting spaces.

Farmland Protection

Farmland protection represents the primary way in which local government’s work intersects with the food system in Dougherty County. The Albany-Dougherty County Comprehensive Plan, last updated in 2016, identifies farmland as important to the economy and culture of the county.5 The comprehensive plan highlights the significant amount of prime farmland and rural character of the county as distinctive assets for future prosperity, especially agritourism opportunities.5 The plan recommends an “urban area boundary” to prevent conversion of agricultural land to other uses.5 Despite provisions calling for farmland protection, the city and county governments have not created legally enforceable policies to protect farmland from development pressures. Outside of farmland protection, there is little mention of food production, distribution, and acquisition challenges and opportunities in the document.

Agritourism Promotion

Local governments recognize that agritourism can be an important strategy for bolstering farm profitability and expanding economic activity within the agricultural sector, particularly in boosting income and enhancing viability of small farms.5 Agritourism also provides venues for educating residents and tourists about local agricultural heritage and food production, enhances quality of life by expanding recreational opportunities, promotes the retention of agricultural lands, and increases opportunities for purchasing and consuming fresh, local, healthy foods.39 Local government is currently evaluating proposals to amend the county zoning ordinance to allow agritourism uses in agricultural districts.32

Regional Planning Commission

Dougherty County actively participates in regional planning processes as part of the Southwest Georgia Regional Commission. As one of Georgia’s twelve regional commissions, the Southwest Georgia Regional Commission works with local governments and state and federal agencies to coordinate regional planning activities and funding programs for the 14-county region.40 Although there is no food policy council or other local governance body in Dougherty County for food system stakeholders to convene and engage in agenda setting or policymaking activities, the regional commission structure offers opportunities for thinking about regional food systems issues.

Ideas for the Future

There are many opportunities for using planning and policy to strengthen food systems in Dougherty County. Local governments can create plans, operate programs, build physical infrastructure, and make public expenditures to create equitable and economically resilient food systems. Precedents for such tools are available from across the country (see the Growing Food Connection policy database for examples). In Dougherty County, plans and policies should prioritize the concerns of the most vulnerable groups in the county, including low-income, African American, urban and rural communities that face barriers to accessing healthy food, as well as jobs and transit. The work of community organizations suggests several starting points for local government action to strengthen the community’s food system including:

Establish a Food Equity Policy Council

The city and county governments could collaborate on establishing a food equity policy council in partnership with local community organizations such as Southwest Georgia Project, as well as Extension, local farmers and residents. Much like food policy councils in the country, the food equity policy council could serve as a formal structure to continue and build on the work of the Growing Food Connections steering committee in the county – but with an explicit goal to serve the most marginalized farmers and consumers. The food equity policy council could make a deliberate effort to engage local government officials from various departments, especially economic development, who are less familiar with and “bought in” to the importance of food systems planning. The council can target its outreach and engagement to smaller farmers in the county and members of groups in the community that are most vulnerable to food security, including African American residents in both urban and rural areas, as well as young people. A goal of the council could be to re-frame discussions around farming and farmland protection in the county to center the experiences and needs of small farmers, vegetable farmers, and Black farmers.

The Food for a Thousand Garden at the St. Patrick’s Episcopal Church in Albany, GA. Image Source: American Farmland Trust

Provide Public Financial Assistance for Food Infrastructure Development

Southwest Georgia Project’s regional food hub project is a critical opportunity for local government to simultaneously strengthen agricultural viability and food security in Dougherty County. The non-profit organization has approached local government officials on several occasions to request a property tax exemption on the building in order to divert limited funds away from paying property taxes and towards covering many of the capital improvements that are required to transform the former grocery store building into a space for the aggregation, processing, and distribution of crops for up to 100 farmers from surrounding counties. The local government has denied these repeated requests, even though it provides financial assistance to recruit and retain outside companies.

Local government can support the development of the regional food hub and other local food infrastructure through direct investment, public loans, and tax incentives that help finance these significant improvements. While these projects entail physical infrastructure development such as the construction or rehabilitation of large abandoned or underutilized buildings, they also require specialized equipment such as refrigerated trucks. There are other ways that local government can support the regional food hub project and food infrastructure development in the county, such as interventions to educate stakeholders, offer business development and technical assistance, and connect local producers. Southwest Georgia Project has identified the need for business development assistance and offered opportunities for local government to purchase or co-own the building with the organization. The building is over 47,000-square-feet, but the organization only needs about a third of the space for the food hub—the remaining space could be used to house grocery stores or other food retail outlets, creating an opportunity for local government to increase food security. Such infrastructure development is often supported by local governments across the country. The policy brief Food Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution, which draws on innovative experiences from across the country, outlines the many ways in which such infrastructure for fresh fruits and vegetables has been supported by local government.41

Incentivize the Sale of Healthy Food

Local government should consider a variety of strategies to increase access to healthy foods, including: attracting or developing grocery stores and supermarkets in underserved neighborhoods; supporting or developing other food retail outlets such as farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture programs, and mobile vendors (and ensuring public benefits can be used at these venues); increasing the stock of fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods at neighborhood corner stores or dollar stores; and promoting urban agriculture such as backyard and community gardens and permitting chicken coops and similar uses. Given the various challenges local government officials have encountered in attracting grocery stores and supermarkets, local government should consider innovative financial, programmatic, and regulatory incentives to allow for production and distribution of food within city limits through farmers’ markets, community gardens, mobile food vendors, and healthy corner stores. Furthermore, programs and policies to increase healthy food options in underserved neighborhoods should align with efforts to support agricultural viability. The policy brief Incentivizing the Sale of Healthy and Local Food details the experience of other urban communities such as Baltimore, Maryland, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Washington D.C. as well as rural Marquette County, Michigan that may be helpful as Albany and Dougherty County take next steps.42

Support the Establishment of Farmers’ Markets

Local government officials should support the establishment of farmers’ markets, particularly in downtown Albany and other areas of the city that are currently underserved by healthy food retail. In addition to property tax abatements, public financing, and technical assistance to support physical infrastructure, local government can also streamline permitting processes and develop policies to further support food infrastructure and business development projects. For example, the adoption of local food procurement policies such as farm-to-school policies, in combination with the development of aggregation and distribution infrastructure, can increase the viability of these projects. Major employers in the county including Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital, Albany State University, and the city and county governments are good places to start with exploring farm-to-institution programs. Dougherty County can draw on examples of promising practices to promote local, healthy procurement from across the country as documented in the policy brief Local, Healthy Food Procurement Policies.43

Provide Incentives for Urban Agriculture

Urban agriculture could help put vacant lots in the city to productive use, contributing to community recreation and neighborhood stabilization, as well as reducing maintenance responsibilities of the local government. Urban agriculture could also provide access to fresh food for residents that face barriers to obtaining adequate, affordable, and culturally acceptable foods in the county. Additionally, urban agriculture could help urban residents who may be disconnected from farming activities that happen in rural areas of the county better connect with this important activity that plays a large role in the county’s history, economy, and identity. A number of local governments from across the country have taken a whole host of actions to support urban (and other forms of) community food production including by creating and implementing agricultural plans (Marquette County, Michigan); adopting supportive land use and zoning regulations (Minneapolis, Minnesota); using public lands for food production (Lawrence, Kansas); and supporting new farmer training and development (Cabarrus County, North Carolina).44 The city and county governments of Albany and Dougherty can leverage their communities’ assets and knowledge to create a supportive policy environment for community food producers.

Research Methods and Data Sources

Information in this brief comes from multiple sources. Quantitative data sources include the 2012- 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates and the 2012 Census of Agriculture, as well as datasets from state education and public health departments. Qualitative data include 12 in-depth interviews with representatives of various sectors of the food system as well as City of Albany and Dougherty County policymakers and staff. Interviewees are not identified by name but are, instead, shown by the sector that they represent, and are interchangeably referred to as respondents, interviewees or stakeholders in this brief. Interviews were conducted from March to July 2015. Qualitative analysis also includes a review of policy and planning documents of Dougherty County, which were reviewed for key policies and laws pertaining to the food system, and a review of the minutes of the Growing Food Connections steering committee meetings. A draft of this brief was reviewed by interview respondents and community stakeholders prior to publication.

Acknowledgments

The GFC team is grateful to the Dougherty County GFC steering committee, Dougherty County government officials and staff, and the interview respondents, for generously giving their time and energy to this project. The authors thank colleagues at the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab and the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo, The Ohio State University, Cultivating Healthy Places, American Farmland Trust, and the American Planning Association for their support. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA Award #2012-68004- 19894), and the 3E grant for Built Environment, Health Behaviors, and Health Outcomes from the University at Buffalo.

Notes

1 Growing Food Connections, “Eight ‘Communities of Opportunity’ Will Strengthen Links between Farmers and Consumers: Growing Food Connections Announces Communities from New Mexico to Maine,” March 2, 2015, http://growingfoodconnections.org/news-item/eight-communities-of-opportunity-will-strengthen-links-between-farmers-and-consumers-growing-food-connections-announces-communities-from-new-mexico-to-maine/.

2 Growing Food Connections, “Dougherty County, Georgia: Community Profile,” May 12, 2016, growingfoodconnections.org/research/communities-of-opportunity.

3 Southwest Georgia Regional Commission, “About the Regional Commission,” accessed May 12, 2018, http://www.swgrc.org/.

4 U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, 2012-2016 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).

5 City of Albany and Dougherty County, Albany-Dougherty County Comprehensive Plan 2026 (Albany, GA: City of Albany Board of Commissioners and Dougherty County Board of Commissioners, 2016), http://www.swgrcplanning.org/uploads/6/1/8/4/61849693/[adopted]_albany-dougherty_comprehensive_plan_dca_6-30-16.pdf.

6 C. Brooks, “Albany District Pecan Growers’ Exchange, National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form,” March 1984, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/176a4f07-f840-4aac-9331-e79a08468fad.

7 For more information on the Albany Movement, see C. Carson, “SNCC and The Albany Movement,” The Journal of South Georgia History 2 (1984): 15-25; S.B. Oates, “The Albany Movement: A Chapter in the Life of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” The Journal of South Georgia History 16 (2004): 51-65; S.G.N. Tuck, Beyond Atlanta: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Georgia, 1940-1980 (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2001).

8 Albany-Dougherty Economic Development Commission, “Area Industries,” accessed May 12, 2018, http://choosealbany.com/area-industries/.

9 A food system is the interconnected, soil-to-soil network of activities and resources that facilitates the movement of food from farm to plate and back.

10 Albany-Dougherty Economic Development Commission, “Major Employers,” accessed May 12, 2018, http://choosealbany.com/business-climate/major-employers/.

11 U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012 Census of Agriculture (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

12 Interview with Farming and Agriculture Representative in Dougherty County (ID 44), March 25, 2015.

13 Interview with Farming and Agriculture Representative in Dougherty County (ID 50), July 1, 2015.

14 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Dougherty County (ID 48), March 26, 2015.

15 Interview with Cooperative Extension Representative in Dougherty County (ID 46), May 18, 2015.

16 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Dougherty County (ID 51), March 25, 2015.

17 Interview with Cooperative Extension Representative in Dougherty County (ID 49), March 25, 2015.

18 For more information on how farmland loss in the U.S. is tied to racial and equity concerns, see J. Gilbert, G. Sharp, and M.S. Felin, “The Loss and Persistence of Black-Owned Farms and Farmland: A Review of the Research Literature and Its Implications,” Southern Rural Sociology 18, no. 2 (2002): 1-30; The Center for Social Inclusion, “Regaining Ground: Cultivating Community Assets and Preserving Black Land,” 2011, http://www.centerforsocialinclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Regaining-Ground-Cultivating-Community-Assets-and-Preserving-Black-Land.pdf; A. Dillemuth, “Farmland Protection: The Role of Local Governments in Protecting Farmland as a Vital Local Resource,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2017), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCPlanningPolicyBrief_FarmlandProtection_2017Sept1.pdf.

19 For examples of local and national press coverage of droughts in Southwest Georgia, see Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “Exceptional Drought Wreaks Havoc in Southwest Georgia,” August 27, 2012, https://www.ajc.com/news/local/exceptional-drought-wreaks-havoc-southwest-georgia/Zzx9n7Kh3Td42zq7JAQeeO/ and National Public Radio, “Georgia Digs Deep to Counter Drought,” August 14, 2012, https://www.npr.org/2012/08/14/158745435/georgia-digs-deep-to-counter-drought.

20 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Press Release: Georgia EPD to Suspend Consideration of Some New Farm Water Permit Applications,” July 30, 2012, http://www.georgiawaterplanning.com/documents/GeorgiaEPD_Newsrelease_AgPermittingSuspension_073012.pdf.

21 Pretoria Fields Collective, “Pretoria Fields Collective,” accessed May 12, 2018, http://www.pretoriafields.com/.

22 J. Wallace, “Microbrewery Project Underway in Downtown Albany,” WALB News, November 7, 2016, http://www.walb.com/story/33650454/microbrewery-project-underway-in-downtown-albany.

23 WALB News, “Special Report: Destination Downtown,” February 11, 2016, http://www.walb.com/story/31189530/special-report-destination-downtown.

24 Interview with Local Government Representative in Dougherty County (ID 42), March 25, 2015.

25 Southwest Georgia Project, “Organization History,” accessed May 12, 2018, http://www.swgaproject.com/.

26 C. Cox, “Food, Ag, Equity Conference Links Local Farmers, Consumers,” Albany Herald, October 23, 2017,

http://www.albanyherald.com/news/local/food-ag-equity-conference-links-local-farmers-consumers/article_17bca9d2-f3a7-570d-a0df-5671091e0861.html.

27 Feeding America, “Map the Meal Gap 2017: Overall Food Insecurity in Georgia by County in 2015,” 2017, http://www.feedingamerica.org/research/map-the-meal-gap/2015/MMG_AllCounties_CDs_MMG_2015_1/GA_AllCounties_CDs_MMG_2015.pdf.

28 Feeding America, “Map the Meal Gap 2017: Child Food Insecurity in Georgia by County in 2015,” 2017, http://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2015/child/georgia/county/dougherty.

29 Georgia Department of Public Health, “Number of Children Receiving WIC, Birth through Age 4,” 2015, accessed from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/.

30 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016 Local Area Unemployment Statistics: Annual Averages (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, 2016).

31 Interview with Local Government Representative in Dougherty County (ID 43), March 27, 2015.

32 Interview with Local Government Representative in Dougherty County (ID 45), March 26, 2015.

33 Interview with Food Retail Representative in Dougherty County (ID 52), March 25, 2015.

34 Second Harvest of South Georgia, “How Our Food Bank Works,” accessed May 12, 2018, http://feedingsga.org/food-bank-works/.

35 Dougherty County School System, “What Does it Cost to Eat at School?” accessed May 12, 2018, https://www.docoschools.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=445534&type=d&pREC_ID=960897. For more information about the Community Eligibility Provision, see “School Meals: Community Eligibility Provision,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, August 8, 2017, https://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/community-eligibility-provision.

36 A. Dillemuth, “Community Food Systems and Economic Development: The Role of Local Governments in Supporting Local Food Economies,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2017), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCPlanningPolicyBrief_EconomicDevelopment_2017Sept.pdf.

37 U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 Census of Governments: Local Governments in Individual County-Type Areas (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2016).

38 The formal name of the planning department is Planning and Development Services Department. The City and County have a long history of working cooperatively to provide services, a relationship formalized in 1999 when the City and County developed a Service Delivery Strategy. While the City and County governments are not formally consolidated, the Service Delivery Strategy essentially leaves the city and county with only four departments in which cooperative agreements are not in place: Personnel, Police, Finances, and Public Works. The City and County submitted a Service Delivery Strategy to the Georgia State Department of Community Affairs in compliance with Georgia’s General Assembly 1997 directive (House Bill 489).

39 A. Dillemuth, “Farmland Protection: The Role of Local Governments in Protecting Farmland as a Vital Local Resource,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2017), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCPlanningPolicyBrief_FarmlandProtection_2017Sept1.pdf.

40 The Regional Commission has served as a designated Economic Development District since 1967 and administers the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) required by the U.S. Department of Commerce. In 2011, the commission published Moving Forward: A Regional Plan.

41 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Food Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCFoodInfrastructurePlanningPolicyBrief_2016Sep22-3.pdf.

42 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Incentivizing the Sale of Healthy and Local Food,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCHealthyFoodIncentivesPlanningPolicyBrief_2016Feb-1.pdf.

43 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Local, Healthy Food Procurement Policies,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2015), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/FINAL_GFCFoodProcurementPoliciesBrief-1.pdf.

44 A. Dillemuth, “Community Food Production: The Role of Local Governments in Increasing Community Food Production for Local Markets,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2017), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCFoodProductionPlanningPolicyBrief_2017August29.pdf.

Community of Opportunity Feature

AUTHORS

Enjoli Hall, University at Buffalo

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

CONTRIBUTORS

Jill Clark, The Ohio State University

Julia Freedgood, American Farmland Trust

Kimberley Hodgson, Cultivating Healthy Places

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

SERIES EDITOR

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

PROJECT COORDINATOR

Enjoli Hall, University at Buffalo

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Brenda Stynes, University at Buffalo

Samantha Bulkilvish, University at Buffalo

Recommended citation: Hall, Enjoli and Samina Raja. “Seeding Food Justice: Community-Led Practices for Local Government Policy in Dougherty County, Georgia.” In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited by Samina Raja, 20 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project, 2018.