Print Version (PDF)

Building on History and Tradition: Community Efforts Strengthen Food Systems in Polk County, North Carolina

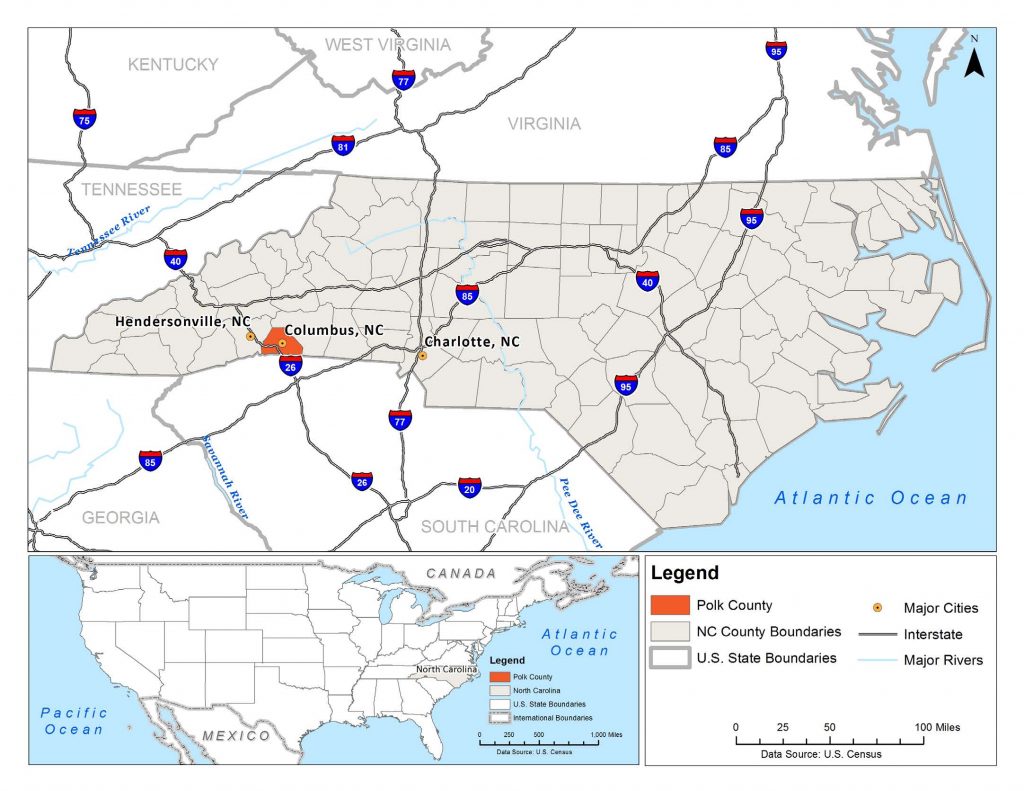

In March 2015, Polk County, North Carolina was selected as one of eight Communities of Opportunities (COOs) in the country with significant potential to strengthen ties between small- and medium-sized farmers and residents with limited food access. Working with the Growing Food Connections (GFC) project team, county stakeholders have since established a steering committee that has charted a vision for the future of Polk’s food system.

This brief, which draws on interviews with Polk County residents and community leaders and secondary data sources, provides information about local government policy opportunities and challenges in the food system to inform the work of the GFC steering committee in Polk County.

The Polk County High School farm uses by-products to make biodiesel.

Image Source: Growing Food Connections

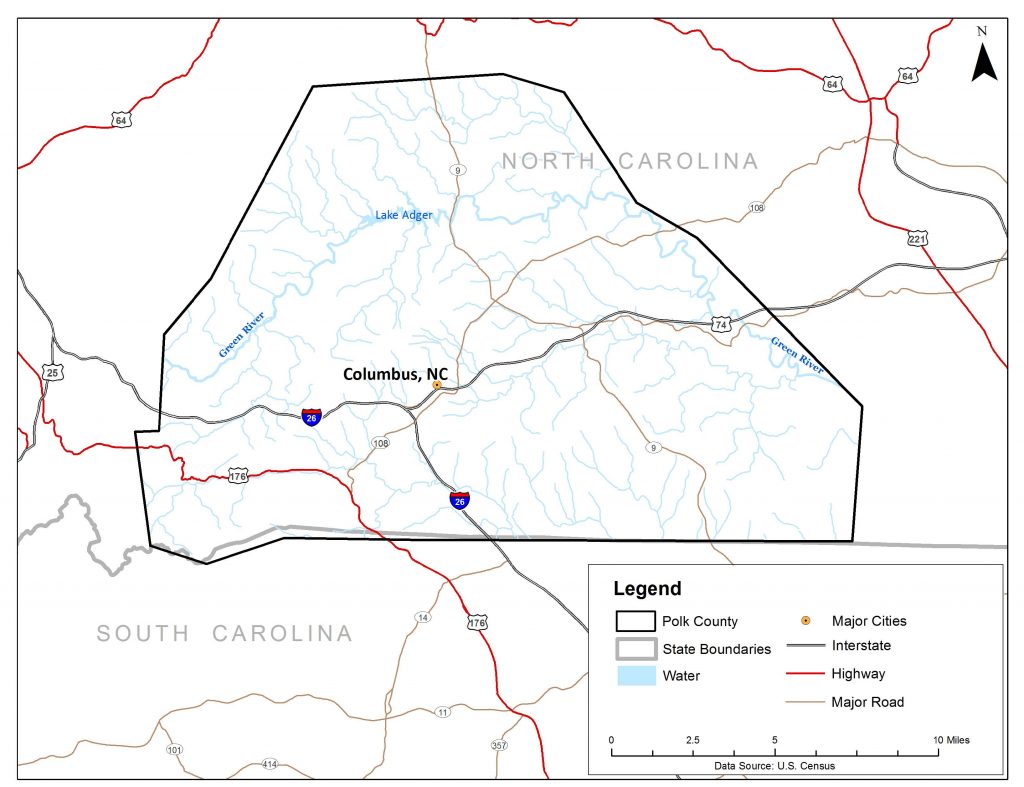

Polk County, located in southwestern North Carolina, is nestled between the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the edge of the Piedmont Plateau. Rugged landscapes of mountains and gorges are interspersed with rolling pastures, cultivated fields, orchards, and vineyards. Polk County residents have a deep commitment to honoring and retaining their rural legacy. Like many rural communities, the county is experiencing a time of transition, population shift, and unique emerging opportunities. Local government and civic society have, through strong joint efforts, reinforced their commitment to well-planned growth that preserves the county’s rural character while simultaneously providing opportunity for all its residents. In Polk County, small- town charm is coupled with immense economic opportunity that stems from its low population density and location in the greater Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion. A world-class equestrian facility attracting tourists from across the globe now augments a long history of raising horses for fox hunting and trail riding. Partnerships in a larger regional network support focused, strategic investment in the immediate local economy. Local government support for agriculture and food as a form of economic development has provided a similar outlet for protecting tradition while creatively expanding opportunity for long-time and new Polk County residents.

BACKGROUND

Affectionately referred to as “a place with 20,000 people and only six stoplights,”1 Polk County is a quintessential rural community. The population of 20,411 people is spread across 237 square miles, creating a low population density of approximately 83 people per square mile.2 The county comprises six townships,3 with three primary population centers of Tyron, Columbus, and Saluda, all with fewer than 1,700 people. A large majority (80%) of the population lives outside the population centers in a rural landscape enriched by forested land, agricultural land, and the mountains. Many residents come from families with intergenerational ties with the region. Polk is one of the few counties that can trace the majority of its current residents back to the original settlers of the land, including several prominent families who were active in the American Revolution. The majority of Polk County residents (93%) are white, although there are small African American (4.5%) and Hispanic (5.8%) populations. The median household income in Polk County ($44,745) is slightly below the statewide average of $46,334, but the percentage of persons living below the poverty level in Polk County (16.7%) is also slightly below the state average of 17.5%.2 Community leaders caution that although average household incomes and employment statistics appear competitive, the data mask economic disparities within the county; the presence of a small number of high-income families may skew the data.1

Unemployment in the county is low (5.1%), which may be attributed to many people working part-time or low-wage jobs, particularly in the service industry.4 More than half of the county’s working-age adults travel outside of the county or the state for employment opportunities.4 Although Polk County and several neighboring counties lost many jobs withthe decline of the textile industry, their location in the Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion provides new opportunities in automobile manufacturing and industry. Private transportation is a near necessity for residents, and people who do not have their own vehicles face challenges in securing employment.5

FOOD SECURITY: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Food insecurity is a concern for some Polk County residents, particularly senior citizens, families with children, and people with low incomes. Food security is defined as the state in which all members of a community have sufficient and adequate access to healthy, affordable, and culturally acceptable foods.6 In comparison to neighboring counties, Polk County has fewer food-insecure people and fewer people with diet-related diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Although Polk County’s population is comparably healthier and less at risk of food insecurity than those in adjoining counties, the broader region is experiencing health setbacks relative to the rest of the country, and particular subgroups are at greater risk. For example, although Polk is ranked as having the second lowest food-insecurity rate in the WNC region (14.2% for Polk County), the Western North Carolina region as a whole has a greater rate of food insecurity than is found in the US.7

Challenges

In rural areas, residents who are food insecure are often not visible to policymakers and planners due to both the low- density population and individuals’ reluctance to appear to need assistance. Poverty in rural Polk County is often tucked away in remote corners, where local government officials and even social-service organizations are not aware of the challenges residents may face, and residents may not be willing to share their concerns.8 Addressing persistent poverty in communities with tight-knit connections requires sensitivity to communities’ perceptions and realities.

In 2010, 44.49% of Polk County students were eligible for free school meals, and 8.8% were eligible for reduced-price school lunches, a significant increase from 2006, when 29.6% of students were eligible for free school lunch and 12.3% were eligible for reduced-price school lunch.9 In part due to the large increase and generous local donors, Polk County now offers free school lunch for all elementary and middle-school children.10 In addition, the school district and the only local food pantry, Thermal Belt Outreach, run a food-assistance program that sends food home with students over the weekend.10

Losing or not having access to personal transportation is a barrier to food security. Polk County is a rural community, and the majority of residents must drive to reach food retail stores. Although the county does have a call-on-demand transportation system, not all residents are aware of how to access the system to plan trips. Lack of access to personal transportation also severely limits employment opportunities, contributing to food insecurity indirectly.10

During interviews, community leaders expressed concern that the limited knowledge of healthier cooking practices worsens nutrition for many Polk County residents.5 Some interviewees noted that even if low-income residents were interested in cooking healthier foods, they might stick to familiar cooking practices for which ingredients are readily available and inexpensive. Families may have little extra money to experiment with other cooking styles that may require more expensive and harder-to-locate ingredients.5

Opportunities

Polk County continues to make strides in increasing access to healthy and local foods for residents. The number of farmers’ markets and farms with direct sales to consumers has increased in the past five years. Currently, Polk has three farmers’ markets spread across the county, all of which allow customers to use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)/Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) funds.11 The number of farmers’ markets, farm stands, and produce stands in the county is higher than the average number of farmers’ markets, farm stands, and produce stands per 1,000 people for Western NC.7 The Polk County Community Foundation provides funding for Double Up Buck programs to expand access to local foods for residents using food-assistance programs.11 All three towns in the county provide space for farmers’ markets to operate.11 Although opportunities to purchase fresh food from local farmers are abundant, there is a widespread belief (both real and perceived) that produce options at these direct-to-consumer locations are overpriced and too expensive for many Polk County residents.12

Small farms make up the majority of agricultural production in Polk County, North Carolina. Image Source: Growing Food Connections

Residents of Polk County have a long history of taking care of their food-insecure residents. Farmers have been known to drop off produce to the food pantry before the sun rises, preferring to keep their donation (and identity) unacknowledged. An active gleaning group provides fresh produce during harvest season to diversify the food options available through emergency food programs. Churches, the public school, and the Boy and Girl Scouts programs also provide food through food drives for pantries.12 Expanded cold-storage facilities in the county have improved emergency food providers’ ability to stock and distribute perishable food items such as meat, produce, milk, and eggs.

Thermal Belt Outreach, an organization that serves all of Polk County, provides emergency food access to families in need. The organization operates the only food pantry in the county and has seen a steady increase in need for food-assistance services in recent years.12 In addition to operating the food pantry and other services, the organization partners with the Polk County School District on a program to provide food for students and families over the weekend. Students at risk of not having a nutritionally adequate diet receive a bag of food for the weekend. The bag of food is placed in students’ lockers when class is in session, to reduce stigma.13 Although the reach of Thermal Belt Outreach and other organizations is large, the need for emergency food assistance exceeds available assistance. Emergency food-service providers are also unable to serve those food-insecure residents who are reluctant to seek assistance.

AGRICULTURE: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

While the now-gone textile industry was once a large employer in the area, agriculture has been the cornerstone of Polk County’s economy for many generations. Prime weather conditions created by the isothermal belt in the county allow for expanded production of certain crops. The isothermal belt is a unique weather condition formed by the belt’s location in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. This thermal belt creates milder winters and cooler summers than those found in geographies both lower and higher in elevation than Polk County. As a result, the growing season in Polk County, particularly near the Tryon- Columbus area, begins earlier and lasts longer.13

Agriculture in Polk County is primarily practiced on small farms scattered throughout the county, accounting for 15.8 percent of the county’s land area.14 Today, the county’s 290 farms are an average size of 83 acres, less than half the statewide average size of 168 acres.15 Nearly all (99%) of the farms are small family farms, many being very small; about one-third of farms (109) report gross sales of less than $1,000.15 Thirty-nine farms in the county report gross sales of over $25,000. The high number of very small farms indicates that farm income is of secondary importance to many farm owners. Half (145) of Polk’s principal farm operators do not consider farming their primary income.16

Principal farm operators in Polk County have some unique characteristics. Farmers in the county are an average of 60.4 years old, two years older than the average age of principal farm operators in the state. Almost half (47.2%) of principle farm operators in Polk County are women, compared to 14.7% of principal farm operators statewide.17

Much of Polk’s agricultural land consists of woodland (35.4%) and pastureland (25.2%), with only slightly under one-third of the land being cropland (29.5%) and about 9.9% dedicated to other uses.15 Pastureland is dedicated to 58 beef cattle farms, two dairy cattle farms, and eight sheep and goat farms, in addition to a large equine industry.18 Polk County farmers are currently expanding their diversified fruit and vegetable production,thanks in part to the efforts of the Agriculture and Economic Development department.

It is curious that although Polk County lost 19 farms between 2007 and 2012, approximately 3,100 more acres of land were put under production during the same years.15 Similarly, the average size of Polk County farms jumped from 68 to 83 acres. In other places such as the Midwest, this could point to farm consolidation, often with corporate ownership over commodity crops. Given the small size of Polk County farms, however (even with the acreage increase), this could point to expansion of farms due to increased market opportunities generated from the growth in farmer’s markets, creation of a food hub, and other direct-to-consumer markets.

The isothermal belt creates favorable conditions for apples and grapes. Fruit and tree-nut farms account for 21 of Polk’s farms, and an ever-expanding viticulture movement is present in the county’s additional 11 commercial vineyards and five wineries that are open to the public.19 For vineyard operators who don’t process grapes on site, many sell their grapes to Biltmore Estate Winery in Asheville, NC. The prime growing conditions paired with the equine and outdoor-enthusiast tourism create opportunities for expanding a grape and wine agritourism sector.19

The development of the Tryon International Equestrian Center has

contributed greatly to Polk County’s economy.

Image Source: Growing Food Connections

The equine industry in Polk County is large and quickly expanding. In 2009, Polk County was home to 3,850 equine animals worth a combined value of $23,395,000.20 Known as Tryon Horse Country, the beautiful scenery attracts trail riders, fox hunters, and horse competitors, which bring tourists who contribute significantly to the county’s economy. The equine industry also supports related equine businesses such as veterinarians, barn builders, farm-equipment sales, truck and trailer sales, and many more. In 2010, the equine industry was believed to have a $15 million direct impact on the Polk economy.21 The equine industry quickly expanded when the Tryon International Equestrian Center, a $100 million equestrian center and resort, opened in 2014. Estimates suggest that the center has contributed an estimated $9.2 million directly to the county’s economy in 2015 and created an estimated 115 jobs locally, with rapid expansion expected.22 The equine industry, and particularly trail riding, while not directly tied to food production, relies on farmland and open-space preservation to retain and attract the equine industry. Opportunities abound for connecting food production with the equine industry.

Challenges

Although many opportunities abound, Polk County farmers still face challenges. The price of farmland in Polk County is particularly cost prohibitive for people who do not inherit a farm from their family, creating a barrier for young people to enter the profession.23 Ties among family and to the land are strong, making the sale of land outside families rare. The average age of principal farm operators in Polk County is older than the average age of farm operators in the state and the country, raising an additional concern.17 For those wishing to retire from farming, very few have viable succession plans for their farmland. Few farmers have an heir who is interested in keeping the farm under production; although they may wish to keep the land, it frequently becomes fallow. The turnover of farmland without adequate succession planning is a large concern for both farmers who rely on the sale of land for retirement and land preservationists who are concerned about large swathes of land becoming available on the market with no protections or easements. New farm operators, both those who inherit and purchase land, are also stymied by the high price of upgrades and improvements to buildings and equipment. Often, old farms in transition were not very profitable and not upgraded with necessary improvements for many years. New farmers are saddled with upgrade expenses in addition to the price of the land.11

Community leaders also report that agriculture-based training can be a barrier for Polk farmers who have few opportunities to learn about new techniques, methods, trends, and market-expansion opportunities.1 Particularly, Polk County farmers lack knowledge of how to diversify their crops to meet high-end niche markets.11 Other community stakeholders are concerned that the farming culture and skills, especially non-traditional agriculture education, are not being passed down because farmers themselves don’t realize the value of their knowledge. Long-time traditional farmers can feel defeated and that their work isn’t valuable, and local knowledge will be easily lost.5 Farmer-to-farmer mentoring, focused on individual relationships, could provide vital informal education on local, regional, and state resources.5

Opportunities

Although Polk County farmers experience barriers, public and private agencies have banded together to uniquely address some of farmers’ key challenges. Polk County was the first county in the state of North Carolina to create, through public funds, an Agriculture Economic Development (AED) office staffed with a full-time coordinator. The Agricultural Advisory Board, an advisory board to the County Commissioners, supports the office.24 This innovative local government action is a signal that agriculture is a valuable part of Polk’s economy and community. By building on the county’s many successes and uniting the agriculture economic-development activities with basic human-needs services, Polk County is well poised to serve as a nationwide example of how low-density rural areas can band together to prime their own economy in a way that provides opportunity for all residents.

Mill Spring Agricultural Center

The Mill Spring Agricultural Center (MSAC) is the heart of the Polk County agriculture community. Private owners donated an unused school building to the Polk County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) in 2009 to serve as an agricultural center, and it has since served as the locus for SWCD, AED, farmland preservation efforts, agriculture education, and the local farming community. Funding for operational costs of the center is obtained by refurbishing and renting out the classrooms as offices and through fundraisers, donations, and grants. The location of the center in the heart of the community, and incidentally removed from county government offices, has made the center accessible and welcoming for farmers across the county. Contained in the building is the Office of Agriculture Economic Development, the Soil and Water Conservation District offices, the county forestry agent, Growing Rural Opportunities (GRO), a farm store, the Equipment and Tool Share Cooperative, demonstration gardens, classroom space, and a community- gathering space. AED uses the space to fulfill their mission of creating marketing opportunities for farmers, farm business-plan advising, consumer education, access to local food, and farmland preservation efforts.24

Agriculture Economic Development (AED) hosts numerous programs and opportunities that support small- and mid-sized farmers. Friends of Agriculture Breakfasts, a monthly community education and outreach event for Polk County farmers and producers, features agricultural research findings and local and regional marketing trends for 60–100 producers every month.25 Active for seven years, the breakfast gatherings are credited with creating cohesion among producers, consumers, citizens, and stakeholders. AED’s Equipment and Tool Share Cooperative, funded by annual farm tours, provides tool and equipment rental such as honey-processing equipment, seed drills, tillers, and more for collective use.11

Growing Rural Opportunities and Growing Food Where People Live

Growing Rural Opportunities was formed in 2015 to build on the work of the Mill Spring Agricultural Center and the Office of Agriculture Economic Development. While these two entities had done much to advance farming in the county, the need for a nonprofit that could work to advance the full food system and serve as a flexible partner to local government agencies was clear. GRO partners include the Cooperative Extension, Mill Spring Agriculture Center, the Office of Agriculture Economic Development, and other agencies.26 This nonprofit addresses farmer and consumer relationships, facilitates creation and strengthening of farmers’ markets, coordinates Grow Food Where People Live (described below), and has established an incubator farm and Land Link Program.27

Growing Rural Opportunities united with Polk County Agriculture Economic Development and Groundswell International to form a new initiative, Grow Food Where People Live. Formed in 2015, the initiative is “designed to improve the health, food security, and economic wellbeing of people in Polk County by supporting them as they grow their own food, learn valuable skills, and organize food-buying clubs to improve their household economies and start market gardens and food-related enterprises to earn more income.”28 The initiative assists in the creation of micro-farms that include gardens, fruit trees, shrubs, and handicap-accessible garden beds located next to low-income housing units. These micro-farms supply large quantities of fresh produce to families with limited food access, while serving as places of learning and community building. In addition to the educational component, Grow Food Where People Live also focuses on economic development through food-based small businesses, partnering with participants to develop small businesses that increase economic independence.29 Both Growing Rural Opportunities and Grow Food Where People Live will serve as entities to unite the agriculture economic-development work with broader activity to address rural poverty and opportunity.

Supportive Private Funding

Private funding has played a key role in food-systems work in Polk County. The Polk County Community Foundation (PCCF) has awarded significant funds to food-systems work in Polk County, both for low-income consumers and producers. They provide funding for a student intern program for high-school students to intern with the Polk County High School farm, and assist with food and client services at Thermal Belt Outreach Ministry.30 The foundation also administers funding for the Culberson Agricultural Development Fund and the Culberson Quality Local Food Initiative Fund, both of which have provided funding for community gardens, farmers’ markets, the high- school farm, sustainable cover crop management systems, and more.31 Recently, they awarded a $3,800 unrestricted grant fund to support local beekeeping efforts.32

LOCAL GOVERNMENT PUBLIC POLICY ENVIRONMENT

Polk County is fortunate to have a local government committed not just to protecting farmland but to actively supporting farming as a viable economic enterprise. Their county commissioner’s office is dedicated to decreasing persistent poverty (thus indirectly increasing food security) for Polk’s low-income residents.12 Polk County has five local government entities: one county government, three municipal governments (Tryon, Columbus, and Saluda), and one special-purpose government (Polk County School District).33 These local governments rely heavily on the Office of Agriculture Economic Development to directly interact with agriculture, but local government public policy also indirectly affects agriculture and food access in numerous ways.

Plans

Polk County’s award-winning 20/20 Vision Comprehensive Plan, adopted in 2010 and undergoing updates in 2016, clearly references the importance of Polk’s rural heritage, wild open lands, and agricultural working lands. Sections of the plan reference the importance of agriculture, viticulture, and the equine industry to the county’s economy and sense of place. The plan serves as a blueprint for future government action, a bequest taken seriously by local government and residents: plans for economic development, agriculture economic development, transportation, and even requests for outside grant money all clearly align with the 20/20 Vision plan. The community- engagement part of the plan was executed with respect and importance, which has clearly translated to how enthusiastically Polk County residents and food-systems stakeholders uphold and reference numerous aspects of the plan.

Polk County also has an economic development policy resulting in an Economic Development Strategic Plan that addresses multiple parts of the food system, including agriculture and food access. The plan aligns with the 20/20 Vision Plan and seeks to create a competitive environment for agriculture and farming. Additionally, the plan addresses barriers to gainful employment through the lens of poverty, food insecurity, and transportation shortcomings.34 The plan’s suggestions for partnering with the Department of Social Services and regional health forums to address employment signal a desire to work broadly across the food system.

The Polk County Transportation Authority’s progressive five- year Community Transportation Service Plan, developed through a community-engagement process, outlines the Authority’s plans for providing enhanced services to better meet residents’ needs. Currently, they provide on-demand transit trips for Polk residents for a modest fee. This service fulfills a vital need for transportation, particularly for Polk’s senior-citizen population, and completed 40,420 trips in 2014. This local and regional transportation service seeks to increase transportation to employment opportunities and is partnering with regional transportation providers to provide greater connectivity to other modes of transportation as well. More frequent access to grocery stores, farmers’ markets, and food banks emerged as a major service need throughout the community-engagement portion of the plan, a key service in helping decrease food insecurity in Polk County.35

Policies

Polk County has a strong agriculture and farmland protection program, including both Voluntary Agriculture Districts (VAD) and Enhanced Voluntary Agriculture Districts (EVAD), which protect over 7,000 acres of farmland. Polk’s VAD is a present- use value taxation program that protects land for a period of ten years and allows the landowner to revoke the conservation easement. Currently, 65 farms, representing 5,640 acres, participate in the VAD program, which has been active for 11 years.25 The EVAD is a newer program that mirrors the VAD program but is irrevocable for ten years. EVADs have protected about 2,041 acres of land on 27 farms.25

In addition to the agriculture districts, Polk County has several other policies that directly and indirectly affect farmland. As part of the county comprehensive plan, no land-use regulations are enforced for active farms, enabling farmers to have full control over buildings and land use on their farms.21 The County’s Subdivision Ordinance, adopted in 2011, requires an environmental-impact statement for development if the environmental-assessment rating totals a specified number of points. Land that increases the number of points includes land adjacent to a farmland preservation area, land adjacent to land trust or conservation properties, and if 33% or more of the project includes prime farmland soils.36 This policy guarantees that Polk County will retain its rural landscapes.

Polk County, and the towns of Tryon and Columbus, has an occupancy-tax policy with potential to indirectly affect agriculture and farming. The 3% tax on overnight stays is used to promote travel, tourism, and tourism-related expenses and, in the case of Columbus, can be used for their general fund. County funding from this tax primarily supports the Polk County Tourism Office. In 2013, this tax resulted in $76,156 generated at the county level, with Tryon and Columbus receiving $16,293 and $19,882, respectively.37 The development of the Tryon International Equestrian Center caused the occupancy-tax fund to spike significantly, resulting in $117,868 in county funding alone in 2015 and continued projected growth with the addition of a resort complex under development.38 In 2013–14, the Polk County tourism budget was $55,520, and by the 2015–16 year, the budget was $160,599. This growth allowed Polk County to modify their part-time tourism position to a full- time director’s position and to add two part-time positions, all funded by the occupancy tax.39 Agritourism efforts of all kinds in Polk County, but particularly wineries and microbreweries, could benefit significantly from funding generated from an increasing occupancy-tax fund.

Initiatives and Projects

In addition to the AED office, other Polk County government departments sponsor initiatives and projects that impact the food system. The Polk County School District, a special-purpose arm of government, operates an extensive agriculture and aquaculture vocational program as an extension of agriscience coursework. Students are able to take coursework in animal science and horticulture while practicing their skills at the high school’s on-campus farm. Featuring a state-of-the-art greenhouse, animal science barn, a dwarf apple orchard, historical garden, a shade house, fish tanks, and agriculture field, the farm provides hands-on education for all students as well as workforce development for students interested in entering the agriculture field.40 Additionally, the school has mobile poultry-processing equipment that they are able to use on local farms.11

Funding

The Polk County Board of Commissioners has provided both steady and one-time strategic funding for food-systems projects. The ongoing funding of a full-time staff person in the Office of Agriculture Economic Development has provided steady leadership in the Mill Spring Agriculture Center and generated grant funds that continue to support food-systems work.

The County Board of Commissioners also allocated three years of funding to Polk Fresh Foods, Polk’s Food Hub. This funding, totaling $122,000 over three years, served as seed money to start the initiative in 2011. Polk Fresh Foods provides a market for local produce, value-added products, and proteins from Polk County farmers. In addition to the seed money they received, Polk Fresh Foods has shown progressive growth in sales. In the initiative’s first year (2012), they had $53,000 in sales. By 2014, the sales increased to $307,000, bringing it to a point of viability that allowed it to be merged with Sunny Creek Farms and run as a private entity in 2015.41 Polk Fresh Foods creates a market for numerous small growers, making the county’s investment in the hub a direct investment in the agriculture economy.

Polk County food-systems work has also been the recipient of outside grant monies that were awarded from the work of the Office of Agriculture Economic Development, the Office of Economic Development, Cooperative Extension, and other county-supported departments. In 2009, the preliminary work behind Polk Fresh Foods was funded by a $10,000 Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Grant that contributed to the development of the Office of Agriculture Economic Development.42 In collaboration with neighboring Rutherford, McDowell, and Cleveland Counties, Polk County was the 2015 recipient of a Stronger Economies Together grant, one of only 21 grants awarded in the country. Dedicated to the development of a regional economic development plan, the team includes key agriculture stakeholders, including the Agriculture Economic Development Director and the Cooperative Extension Service Director.25

IDEAS FOR THE FUTURE

Gifted with a resilient entrepreneurial spirit, thriving rural communities, and a dedication to embracing opportunity, Polk County is uniquely positioned to become a leader among rural communities seeking to embrace agriculture as a way to build their economy and create healthy communities. Key ideas for future policy and implementation efforts to strengthen food systems are outlined below.

Embrace and Amplify Locally Rooted Ideas and Solutions

With a population of about 20,000 across the whole county, Polk County is a very rural community. Rather than allowing the low population to hold the community back from enacting healthy community-planning methods seen in other communities, Polk has embraced its rural heritage and given momentum to an existing creative and entrepreneurial spirit. The county has created a loose regulatory environment in which residents are able to experiment and build businesses. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Polk County’s support of the Mill Spring Agriculture Center and the Office of Agriculture Economic Development. Polk County has the opportunity to expand this “can-do” attitude of governing and policymaking to encompass food-security efforts, focusing on locally rooted solutions, the informal economy, and community connections. The proven track record of using this approach to strengthen agriculture can be similarly invested in ensuring all Polk County residents are food secure by connecting the food economy to workforce development, educational opportunities, and civic society.

Support and Build a Network of Traditionally Underrepresented Farmers

Female farmers are traditionally underrepresented in the farming field, yet almost half of all principal farm operators in Polk are women. Nationally, traditionally underrepresented farmers operate smaller farms, with a focus on fruit and vegetable production, specialty crops, diverse herds, alternative marketing strategies, and sustainable practices, similar to those in Polk County.43 Polk County offers the supportive community that many women farmers desire. Building on educational networks and communal activities such as tool-share programs and group workdays has proven effective in other states for supporting women and traditionally underrepresented farmers. Supporting and building on Polk’s networks and educational programs will continue to empower underrepresented and underserved farmers in Polk County. There is also opportunity for Polk’s small farms to be ideal locations for incubator farms, apprenticeships, and other programs that boost underrepresented farmers who are starting agriculture careers. In addition, the USDA Farm Service Agency offers special micro-loan and credit programs for women and minority farmers, particularly women and minority farmers engaged in organic, sustainable, specialty, or direct-to-consumer production as is practiced in Polk County.44 Technical support to help Polk’s women and minority farmers take advantage of these programs may bring new credit opportunities to many Polk farmers.

Direct Tourism Revenue to Support Local Food Systems

Polk County has an opportunity to strategically direct new revenue from their growing tourism sector in a way that ensures that all Polk County residents benefit. For example, occupancy- tax money, designed to go specifically to tourism, can be used to bolster Polk’s growing agritourism industry. Investing in processing and infrastructure for wineries, breweries, farm stores with value-added goods, and artisanal butcheries adds to the agrarian charm of Polk County, keeps visitors in the county longer, highlights entrepreneurial activities, and directly impacts farm viability. Additionally, both Polk residents and visitors value the scenic agricultural and natural landscapes of Polk County. A percentage of tax revenue from increased tourism could also be diverted to a fund for preserving farmland and investing in food- system infrastructure.

One of Polk’s growing tourism engines is the Tryon International Equestrian Center (TIEC). The TIEC has the potential to increase revenues for Polk County across the board. The preliminary economic impact statement projected that approximately $9.2 million was added to the local economy in the first year of operation.22 Small businesses, especially service and retail businesses, can benefit greatly from this injection of tourist money. The TIEC could also have a direct impact on Polk County employment by requiring a percentage of hires to be Polk County residents or by investing in job-training programs to prepare Polk County residents with the right skills for TIEC jobs.

Coordination to Facilitate Institutional Purchasing

Currently, few if any farmers grow enough to sell directly to Polk’s hospitals, schools, and local government entities. The Agriculture Economic Development office has facilitated aggregation to allow farmers to be able to sell to restaurants both locally and in the broader region. Continuing to grow the number of farmers selling to Polk Fresh Foods, coordinating key crops among multiple farmers, and coordinating with Polk’s institutions to adopt supportive local purchasing policies could expand a local market.

Celebrate Food-Based Traditions

Community stakeholders speak with fondness of the rich history of food-based traditions in Polk, including community canning days, making molasses, and beekeeping. Continuing to celebrate, preserve, and share these traditions is just as vital as preserving farmland and rural landscapes. Activities that foster community cohesiveness, build relationships, and actively incorporate all residents contribute to decreasing food insecurity, especially in rural communities.45 Such events can also help build cohesiveness among long-time residents and newcomers in communities that are experiencing influx of new residents, as Polk expects in the future.

Continue to Engage in Active Farm-Succession Planning

Polk County has many of the characteristics that new landless farmers seek, and many senior farmers are ready to rent or sell land. The county has also attracted retirees who are interested in farming post-retirement. Continuing to engage in farmer-to-farmer conversations about farm transfer is critical for the future of Polk County farming, particularly as potential land speculation from the Tryon International Equestrian Center could beckon senior farmers to sell to those planning non- farm uses. Fortunately, Polk has a strong Office of Agriculture Economic Development that is tightly intertwined with the farming community, to facilitate these discussions. Because of the tight-knit farming community, Polk is well situated to experiment with innovative land-tenure techniques, and attract out-of-town young farmers who could strengthen land-preservation movements and contribute to Polk’s overall economy (informational resources are available from American Farmland Trust at www.farmland.org).

RESEARCH METHODS AND DATA SOURCES

Information in this brief is drawn from multiple sources. Quantitative data sources include the 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates and the 2012 US Census of Agriculture. Qualitative data include 15 in- depth interviews with representatives of various sectors of the food system as well as Polk County policymakers and staff.

Interviewees are not identified by name but are, instead, shown by the sector that they represent, and are interchangeably referred to as interviewees, community leaders, or stakeholders in the brief. Interviews were conducted from April 2015 to March 2016. Qualitative analysis also includes a review of the policy and planning documents of Polk County, which were reviewed for key policies and laws pertaining to the food system, and a review of the minutes of the Growing Food Connections steering-committee meetings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The GFC team is grateful to the Polk County GFC steering committee, Polk County government officials and staff, and the interview respondents, for generously giving their time and energy to this project. The authors thank colleagues at the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab and the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo, Ohio State University, Cultivating Healthy Places, the American Farmland Trust, and the American Planning

Association, for their support. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA Aware #2012-68004-19894).

NOTES

1 Interview with local government representative in Polk County (ID 84), 2015.

2 United States Census Bureau, Quick Facts, Polk County, North

Carolina (Washington DC: United States Census Bureau, 2015).

3 The townships are Cooper Gap, White Oak, Columbus, Green Creek, Tryon, and Saluda.

4 Polk County Office of Economic Development, Economic Development Annual Report (Columbus, NC: Polk County

Office of Economic Development, 2016).

5 Interview with consumer advocate representative in Polk County (ID 81), 2015.

6 K. Hodgson, S. Raja, J. Clark, and J. Freedgood, “Essential Food Systems Reader,” In Growing Food Connections (Buffalo: University at Buffalo, 2013).

7 J. T. Eshleman, M. Schroeder-Moreno, and A. Cruz. The Western North Carolina Appalachian Foodshed Project Community Food Security Assessment (Raleigh, NC: Appalachian Foodshed Project and North Carolina State University, 2015).

8 Interview with local government representative in Polk County (ID 83), 2015.

9 Economic Research Service, “Students Eligible for Free Lunch, Polk County,” (Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture, 2010).

10 Interview with local government representative in Polk County (ID 80), 2015.

11 Interview with local government representative in Polk County (ID 77), 2015.

12 Interview with consumer advocate representative in Polk County (79), 2015.

13 Thermal Belt Outreach Ministry, “Feed-a-Kid Program,”http://www.tboutreach.org/feed-a-kid-program.html.

14 United States Department of Agriculture, Census of Agriculture: Farms, Land in Farms, Value of Land and Buildings, and Land Use: 2012 and 2007 (Washington DC: National Agricultural Statistics, 2012).

15 United States Department of Agriculture, Census of Agriculture County Summary Highlights (Washington DC: National Agricultural Statistics, 2012).

16 United States Department of Agriculture, Census of Agriculture Net Cash Farm Income of the Operations and Operators (Washington DC: National Agricultural Statistics, 2012).

17 United States Department of Agriculture, Census of Agriculture Operator Characteristics (Washington DC: National Agricultural Statistics, 2012).

18 United States Department of Agriculture, Census of Agriculture: Farms by North American Industry Classification System (Washington DC: National Agricultural Statistics, 2012).

19 Holland Consulting Planners, Polk County 20/20 Vision Plan Update (Polk County, NC: Polk County Board of Commissioners, 2016).

20 Equine Study Executive Committee, Agricultural Advancement Consortium, North Carolina’s Equine Industry (Raleigh, NC: The Rural Center, 2009).

21 Holland Consulting Planners, Polk County 20/20 Vision Plan,

(Polk County, NC: Polk County Board of Commissioners, 2010).

22 I. Ha, A Preliminary Economic Impact Study of Visitors at Tryon International Equestrian Center (Mill Spring, NC: Western Carolina State University, 2016).

23 Interview with local government representative in Polk County (ID 82), 2015.

24 Polk County Farms, Polk County Agriculture Economic Development, http://polkcountyfarms.org/ag-economic- development/.

25 Polk County Office of Agriculture Economic Development, Agricultural Economic Development, Travel & Tourism, Economic Development Annual Report, Polk County, North Carolina: FY 2015-2016 (Columbus, NC: Polk County Office of Economic Development, 2016).

26 B. De Bona, “GRO to Nurture Farmers, Local Food Movement,” Times-News, Blue Ridge Now, April 1, 2016.

27 Growing Rural Opportunities, “About Us,” http://growrural.org/about-us/.

28 S. Klein, “Grow Food Where People Live Program Expanding,” Tryon Daily Bulletin, March 24, 2016.

29 B. Kerns, “Developing Small Businesses Based Around the Local Food System,” Tryon Daily Bulletin, September 13, 2016.

30 C. Barber, “PCCF Funds High School Farm Interns,” Tryon Daily Bulletin, January 12, 2012.

31 Polk County Community Foundation, “Competitive Grants,” http://www.polkccf.org/index.php/grants/for-organizations/ competitive-grants.

32 Polk County Board of Commissioners, “Public Hearing and Regular Meeting” (Columbus, NC: Polk County Board of Commissioners, 2015).

33 United States Census Bureau, Census of Governments: Local Governments in Individual County-Type Areas (Washington DC: United States Census Bureau, 2012).

34 D. Dodson, Economic Development Policy and Strategic Plan for Polk County, NC (Polk County, NC: Polk County Board of Commissioners, 2014).

35 Polk County Transportation Authority, Community Transportation Service Plan (Polk County, NC: Polk County Transportation Authority, 2015).

36 Polk County Board of Commissioners, Subdivision Ordinance of Polk County, NC. Article 5 (Polk County, NC: Polk County Board of Commissioners, 2011).

37 Magellan Strategy Group, Profile of North Carolina Occupancy Taxes and their Allocation, (Asheville, NC: Magellan Strategy Group, LLC., April 2016).

38 S.Q. Hughes, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of Polk County, North Carolina, (Columbus, NC: Polk County Government, 2015).

39 Polk County Board of Commissioners, Polk County NC Annual Recommended Budget (Polk County, NC: Polk County Board of Commissioners, 2016).

40 D. Scherping, “Saluda-PCHS Farm,” http://inside.polkschools.org/announcements.

41 L. Justice, “Polk Fresh Foods Plans to be Self-Sufficient Next Fiscal Year,” Tryon Daily Bulletin, June 17, 2015.

42 Sustainable Community Innovation Project, PolkFresh TradePost Project: A Strategy to Implement Polk County’s 20/20 Vision Plan for Sustainable Community Development (Mill Spring, NC: Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education, 2011).

43 N.E. Kiernan, M. Barbercheck, K.J. Brasier, C. Sachs, A.R. Terman, “Women Farmers: Pulling Up Their Own Educational Boot Straps with Extension,” Journal of Extension 50.5 (2012).

44 United States Department of Agriculture, Minority and Women Farmers and Ranchers, http://www.fsa.usda.gov/programs-and-services/farm-loan-programs/minority-and-women- farmers-and-ranchers/index.

45 L.W. Morton, E.A. Bitto, M.J. Oakland, and M. Sand, “Solving the Problems of Iowa Food Deserts: Food Insecurity and Civic Structure,” Rural Sociology 70.1 (2005): 94–112.

Community of Opportunity Feature

AUTHORS

Jennifer Whittaker, University at Buffalo Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

CONTRIBUTORS

Jill Clark, Ohio State University

Julia Freedgood, American Farmland Trust Kimberley Hodgson, Cultivating Healthy Places Subhashni Raj, University at Buffalo

SERIES EDITOR

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

DESIGN, PRODUCTION and MAPS

Samantha Bulkilvish, University at Buffalo Kelley Mosher, University at Buffalo

Clancy Grace O’Connor, University at Buffalo Brenda Stynes, University at Buffalo

COPY EDITOR

Ashleigh Imus, Ithaca, New York

Recommended citation: Whittaker, Jennifer, and Samina Raja. “Building on History and Tradition: Community Efforts to Strengthen Food Systems in Polk County, North Carolina.” In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited by Samina Raja. 11 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project, 2017.