Print version (PDF).

Building on the Strengths of Land and Sea: Policy Opportunities for Strengthening the Food System in Cumberland County, Maine

In March 2015, Cumberland County, Maine was selected as one of eight Communities of Opportunities (COOs) in the country with significant potential to strengthen ties between small- and medium-sized farmers and residents with limited food access. Working with the Growing Food Connections (GFC) project team, county stakeholders have since established a steering committee that has charted a vision for the future of Cumberland’s food system. This brief, which draws on interviews with Cumberland County stakeholders and secondary data sources, provides information about local government policy opportunities and challenges in the food system to inform the work of the GFC steering committee and stakeholders in Cumberland County.

Cultivating Community operates Boyd Street Urban Farm, which has individual community garden plots and programming for youth.

Image Source: Growing Food Connections

Background

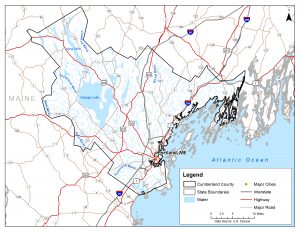

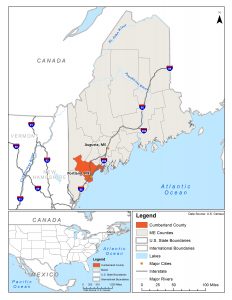

Cumberland County, located along the southern coast of Maine, is home to a deep tradition of fishing, particularly shellfish, small working farms up and down the coast, and is distinguished as a prominent foodie region, attracting renowned chefs looking to share their culinary skills in a small-town atmosphere.

The county sits on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. The most populous county in Maine, it includes the cities of Portland, South Portland, and Westbrook, along with 25 towns. Bon Appétit named the City of Portland “America’s foodiest small town,” and with that distinction, the city is sought out by tourists and locals alike to taste the latest local culinary fare.

Cumberland County has a population of 284,351, with 22.3% of the population residing in the City of Portland, the largest city in the state of Maine.1 Over 90% of the Cumberland County population identifies as white (263,363 people).1 There are 7,552 people that identify as black or African American, and 5,297 people identify as Hispanic or Latino.1 A small number of the population is foreign born; 17,869 people reported being either a naturalized citizen or not a U.S. citizen.1

The economy in Cumberland County is fairly stable, with a median household income of $59,560 and an unemployment rate of 5.8%.1 About 8% of the population has an income that is below the poverty level. Affordable housing is a concern for residents of Cumberland County, especially for renters. Forty-two percent of renters spend over 35% of their income on housing, compared to those in owner-occupied housing units, who spend 24% of their income on housing.1

Among public-health issues, drug-related deaths are reported to be a concern. Like many communities across the United States, deaths from drug overdose, in particular heroin, have been on the rise across the state of Maine since 2011. From 2012–2014, the rate of drug-overdose death in Portland/Cumberland County was 16.3 per 100,000, higher than the state rate of 13.73.1

The education, health-care, and social-assistance industries are the largest sectors of employment in Cumberland County, with 28% of the population employed in these industries. Retail trade is the second largest industry, providing almost 13% of jobs. Small percentages of the population work in agriculture/forestry/fishing and hunting, wholesale trade and transportation, and warehousing (a combined 7%),1 even though Portland is one of the chief trading ports on the Atlantic coast, with a total annual seafood tonnage of 12,898,861 in 2014.29

The ethos of Cumberland County, a small coastal city surrounded by established rural communities, is based on a strong work ethic as well as a desire to support the local economy and maintain limited development.

Food Security: Conditions, Opportunities, and Challenges

Location of Cumberland County, Maine

Image Source: Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab

Even with the abundance of local food, food-related disparities exist throughout Cumberland County. Several groups of people have limited access to food, in part caused by income disparities. Recent refugees and asylum seekers coming to Cumberland County face challenges securing reliable work opportunities. The social-support network particularly underserves asylum seekers because they are ineligible for the state-run Maine General Assistance Programs and are unable to work while their applications are pending. However, the City of Portland is using its own resources to provide assistance for basic needs for asylum seekers. The Maine General Assistance Office provides assistance to individuals unable to pay for basic monthly needs such as rent, food, non-food items, medication, fuel, utilities, and other essential services. Funding is provided through the state and administered by local municipalities.2

Rural poor in the county, also food insecure, include seniors and women with school-age children.3 Seniors living in the rural areas of Cumberland County find that lack of transportation hinders their access to affordable, healthy food on a regular basis. Limited transportation systems for seniors are a systemic concern with long-term implications, as young people migrate out and older people migrate into the rural areas of the county and, thus, emerge as a growing percentage of the population. For seniors, hunger partly results from resource constraints and limited physical access. Many seniors are on a limited or fixed income and are unable to leave their home to purchase food. Those individuals who are near retirement age may have lost their jobs in the nationwide Recession of 2008 and are having trouble getting reemployed. They are also part of the food-insecure population.4

Cumberland County residents are aware of the prevalence of food insecurity and, according to a University of Maine Cooperative Extension representative, of “a strong volunteer base that helps to work towards meeting the needs.”5 There is a strong desire to look out for and provide for one’s own people.3 Food pantries make up a significant portion of the volunteer base working to improve food security. There are 50 food pantries in Cumberland County.6 Most towns in the county have a food-distribution site. More recently, food pantries have been established in the suburban towns of the county. In some towns, only residents of the town are eligible to obtain food from the local pantry. A community stakeholder reports, “The poorer the town, the more restrictive they are. They want only their townspeople served . . . The richer the community, the better the food . . . So in Freeport and Falmouth, a lot of fresh fruits and vegetables…”3 Food pantries face logistical concerns when handling fresh produce. Workers at food pantries that are able to stock local produce have observed that it often gets passed over for more convenient foods.5

Three local agencies provide programming to improve food access throughout Cumberland County: Mid-Coast Hunger Prevention, the Good Shepherd Food Bank, and Wayside Food Programs. Mid-Coast Hunger Prevention has become a resource for food-security work in a 12-town region in southern mid-coast Maine. A local government representative reported that there has been a significant increase in people utilizing the soup kitchen through Mid-Coast Hunger Prevention.7 Mid-Coast Hunger Prevention is also the recipient of the Brunswick Topsham Land Trust (BTLT) Common Good plot, a donation plot that is part of a larger community garden owned and managed by BTLT.8 The Good Shepherd Food Bank is the state of Maine’s food bank.9 The food bank operates a mobile pantry with fresh fruits and vegetables for seniors.4 The bank has established an arrangement with local farmers to grow produce, which is then purchased by the Good Shepherd Food Bank.10 Wayside Food Programs has two primary programs: a community meals program and a food rescue program. The purpose of the community meals program is to provide supplementary meals to community members when they are unable to purchase food to create their own meals. Programs such as Wayside Food Programs provide food-gap services for those struggling to make ends meet. The food rescue program has been instrumental in redistributing 1,087,248 pounds of rescued food to more than 40 partner agencies feeding households throughout Cumberland County.11 Even though there are strong partnerships to reduce food insecurity, there remain additional opportunities to provide connections between consumers and producers. As one community stakeholder reported, “[the county needs] to fix the food system at the food access level.”10

Food insecurity is linked to poor economic prospects for several segments of the population. Over the past 15 years, job loss and job uncertainty have increased in Cumberland County. Portland-South Portland Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) experienced a 7% peak unemployment rate in February 2010 during the nationwide economic recession and has slowly recovered to prerecession rates.30 Community leaders cite the need for a livable wage as a priority for improving food security. An interviewee noted that the “biggest barrier is [that] people don’t have the money to purchase healthy, nutritious food consistently.”10 In the past, policymakers proposed a ballot measure to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour in the City of Portland, which could have alleviated food insecurity.10 Although the measure did not pass, the city council did approve to amend its city code (Chapter 33) to establish a new citywide minimum wage of $10.10/hour, an increase from the previous level of $7.50/hour. The newly established minimum wage applies to employers with businesses in the City of Portland.12

Local leaders recognize that those who are food insecure face the dual bind of monetary and time constraints. One local government representative noted, “Our food security issues come right down to poverty. Life isn’t stable enough for those in poverty to be able to garden. They may have the know-how and the desire but it comes down to time. Time is a resource. Giving a garden space to those in poverty will not solve the food security issues.”2

The high cost of food in Cumberland County is related to high commuting costs; high heat and utility bills because of the colder climate for the majority of the year; food transportation costs based on transportation networks and routes to Maine; and a less agile economy in which those hit hard by the recession are finding it difficult to rebound.10

Much of the effort to promote food security in Cumberland County is happening at the grassroots level and is organized by local not-for-profit agencies. Because of the high needs in the county, even agencies whose mandate is not food-related contribute to programming on food security.4 Farmers’ markets are an opportunity to provide local produce to Cumberland County residents. Although Maine is located in the colder northeastern region of the country, there are 92 farmers’ markets in the state, with 13 located in Cumberland County.13 One consumer advocate states, “We are lucky that there is a farmers’ market in every town that has more than 5,000 people in the state of Maine.”14 The price point of grocery stores and supermarkets is out of reach for 20% to 30% of the population: renters, new Mainers, individuals working minimum-wage jobs, and those with one income and children.15 Farmers’ markets can serve as the access point to local, affordable produce. A community stakeholder posed the question, “How do you create easy access to locally produced food, quality food at an affordable price? You need to make buying local food part of people’s routine, rather than making it an event.”16 Cumberland County farmers’ markets have the opportunity to shift the traditional farmers’ market format so that it better serves all residents and increases access to fresh, affordable local food.

Food and Agriculture Production: Conditions, Opportunities, and Challenges

Cumberland County has a rich heritage of small-scale agriculture and food production, including a sizable seafood industry. In 2014 it was reported that food producers generated about $65 million, including $45 million in lobster catch alone, in farm and fish products, annually.

Cumberland County has 718 farms, with an average size of 87 acres.17 The vast majority of the farms (630) are smaller than 180 acres.17 As in the state of Maine overall, small- and medium-sized farms are the foundation of agriculture in Cumberland County, and the practice of large-scale agriculture is limited.8 Almost 64% of farms in Cumberland County are small- to medium-sized farms. Small-scale producer-to-consumer relationships have a long history in the community.8 Over 20% of farms (23.7%) in Cumberland County sell some products directly to consumers, compared to the national percentage of 6.46%.18 In Cumberland County, 14 farms sell products directly to members through community-supported agriculture (CSA) operations.13

Cumberland County is a significant contributor to Maine’s well-known lobster fishing industry.19 In 2014, a record year for fishermen, Cumberland County reported 11,655,792 pounds of live lobster landings, or 9.4% of the statewide capture of 123.7 million pounds. The county’s catch generated $45.96 million in value, comprising 10% of the statewide sale of $456.9 million. Maine’s huge lobster industry, which provides 80% of all US lobster, supports a larger industry. Statewide, the lobster trade also supports three million lobster traps fielded by more than 5,000 licensed lobstermen and women.

As of 2014, Portland (in Cumberland County) was one of the top three Maine ports for value of seafood shipped on a commercial fishing vessel, according to the Department of Maine Resources. The Portland Fish Exchange began in the 1980s and was the nation’s first all-display fish market. The exchange is an enterprise supported by the City of Portland and was capitalized with three rounds of funds from the US Economic Development Administration (EDA).15 The International Marine Terminal, also located along the seaport in the City of Portland, supports refrigerated container service to Europe. Recently, a $30 million bid was initiated to expand the capacity of the cold-storage warehouse for Maine food exports.15

Challenges

Despite a rich food and agricultural heritage, starting and operating a farming business has its own set of challenges in Cumberland County. The economic prospects of farmers are limited. Sixty-six percent earn less than $10,000 a year and have a net loss of $8,000.15 Agriculture and rural infrastructure have survived in part because there are few development pressures in Maine.14 Increasingly, agriculture is beginning to feel pressure on farmland and land costs, making farming economically prohibitive, especially for beginner farmers.

Beginner farmers in the county have a tough time trying to start a business.5 It is challenging to find land suitable for farming that is close to consumer markets.5 Moreover, a large portion of the population is still unaware of the local foods available.5 The University of Maine Cooperative Extension helps overcome this disconnect by making connections between local producers and consumers and offers training courses to help beginner farmers.5

Farmers must navigate and manage state regulations, which is especially challenging for small-farm operators. The increase in the number of federal and state food-safety regulations increases the cost of business for farmers. Unemployment taxes are also a challenge for businesses, especially for seasonal businesses.16 As is common for many small-farm operators, at least one person working on the farm often has a primary occupation other than farming. In Cumberland County, 384 farmers report this dependence on off-farm employment.20

Variability in market prices has also been a concern for many dairy farmers, much like in the northeast generally. Many dairy farmers have gone out of business because of the industry’s instability.5

Local food producers struggle to have reliable access to consumers, such as with local cheese.5 One Extension interview respondent stated, “This is the economics of business success: help farmers stay in business, and make wise business decisions and produce and market their products so that they can stay in business.”5

The fishing industry has its own unique challenges, including threats from coastal development and ecological concerns. Several coastal towns in Cumberland County use coastal protection zones to manage and regulate growth in the coastal areas and to add protections to support the shellfish industry. Prior to 2014, there were nine active aquaculture operations in New Meadows River, an embayment that experiences little fresh water flow. A declining environment faced with pollution, invasive species, and warming waters along the coastline is threatening aquaculture and has made New Meadows River a prime location for aquaculture and mussel farming, with 10 additional permits issued in 2014.7 The value of fisheries has declined over the past decade possibly because of acidity and overfishing.3 Climate change is also having an impact on the shellfish industry through rising sea levels.5

Community-led Initiatives to Strengthen Agriculture and Food Systems

Several community-led efforts have emerged to respond to challenges in the Cumberland County food system. For example, the Brunswick Topsham Land Trust (BTLT) is actively engaged in strengthening agricultural viability and promoting food access in the towns of Brunswick and Topsham. BTLT owns 320 acres of farmland, called Crystal Springs Farm, which is leased to a local farmer (the trust recently established a 50-year lease with the farmer, who runs the largest CSA in Maine). The land trust also organizes and manages one of the largest farmers’ markets in the state, the Crystal Springs Farmers’ Market, on its property.8 There is high demand for farmers’ markets among Cumberland County residents. Farmers can choose which markets are best for their products.5 Local government-representative respondents view farmers’ markets as somewhat self-organizing in nature. One interviewee describes “most farmers’ markets in Maine [as] a bunch of farmers who have agreed to show up on the same corner on the same day at the same time.”2

A strong movement of backyard do-it-yourselfers who grow produce for subsistence exists in the City of Portland. Portland has over 300 community garden plots, an increase from 130 garden plots. In 2015, the demand for garden plots continued to grow, with a reported waiting list of about 150 people. As additional garden plots are added, community interest grows as well, leading to a positive feedback loop.14 Lead contamination is a potential challenge and concern, particularly because community members are interested in community gardening.2 All schools in the Portland Public School system, which includes 11 elementary schools, three middle schools, and three high schools, have a school garden.2

Residents’ interest in apiaries in the City of Portland is strong as well. There are over 100 privately held beehives in the City of Portland.2

As several respondents stated, supporting local farmers and farming is engrained in the culture of Mainers, and Cumberland County is no exception. “ . . . It is not just about setting land aside – we have to make sure it is actively managed for agriculture or that we are making sure we are getting access to people and providing education.”8 The need for additional consumer advocacy and programming continues. An Extension representative observes, “The agriculture community doesn’t place a high enough emphasis on the importance of consumer education and food literacy.”5 A successful local food movement in Cumberland County needs a stronger focus on educating consumers on the value of agriculture.

Small- and medium-sized farms make up the majority of agricultural production in Cumberland County, Maine.

Image Source: Growing Food Connections

Local Government Public-Policy Environment

The local government public-policy environment is fertile for strengthening the county’s food system. A countywide government, three city governments, and 25 township governments serve Cumberland County. In addition, six school districts and 21 special district governments serve the county.21 Because of Maine’s home-rule mandate, governance in Cumberland County is largely the responsibility of local municipal governments, either towns or cities. County government has limited jurisdiction, and its responsibilities include providing county sheriff services, managing and operating the Cumberland County Jail, and providing a county court system.3 The Cumberland County government has five county commissioners representing the five districts of the county.5 Town Selectmen, who make up the budget advisory committee, provide municipality-specific information to the county commissioners. The county commissioners use the municipality-specific information to develop the county budget.5

In Cumberland County, the public conversation regarding food-systems work has shifted positively in the past 14 years, although there is a lack of funding from the state to support local programs.14 One consumer advocate respondent described the Cumberland County local government’s engagement in food policy as follows: “Local government has not sought out direct public input from residents but has instead worked through existing advisory groups such as Cumberland Food Security Council, Public Health Council and Healthy Maine Partnership Advisory Council.” 4

At the county government level, the Cumberland County Office of Community Development has used Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) money to fund many efforts that support the local food-system infrastructure, including “funded activities to distribute foods from food pantry warehouses.”3 The county has also leveraged federal funds from the Community Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW) program, which provides a long list of Cumberland County examples of public-dollar investments in food work.3 Over the past five years, the county government has become more engaged in food-systems work through the Cumberland County Food Security Council (CCFSC). The CCFSC was established following a food-systems assessment, Campaign to Promote Food Security, conducted in 2010 by the Muskie School of Public Service. The Campaign to Promote Food Security increased community awareness about food security and food access. The United Way of Greater Portland made a three-year commitment to support the CCFSC. The Good Shepherd Food Bank became the fiscal agent for CCFSC. The CCFSC supported a Child Nutrition Reauthorization Forum in 2015.10 Most recently, the CCFSC conducted a Cumberland County Food Systems Summit in May 2016 and was the lead organizer in Feeding the 5,000 in October 2016.

In addition to CDBG funds, the Cumberland County government also invests significant resources annually in the University of Maine Cumberland County Cooperative Extension. There is also a strong partnership between the Cumberland County government and the Town of Bridgton. The two local governments applied and received a USDA Local Food Promotion Program planning grant, which spearheaded the report “Building Support for Community-Based Foods in the Lakes Region of Maine” in September 2016.

At the subcounty level, several cities and towns are actively rebuilding community food systems. The City of Portland, for example, has taken several steps to strengthen the food system in recent years. Former Mayor Michael Brennan established the Mayor’s Initiative for a Healthy Sustainable Food System in April 2012, which morphed into the Shaping Portland’s Food System initiative.2 As part of the Mayor’s Initiative, the City of Portland Department of Parks, Recreation, and Facilities manages and oversees the city community gardening program in partnership with Cultivating Community, a local not-for-profit organization. The Department of Parks, Recreation, and Facilities oversees and maintains nine community garden sites. Most recently, the Portland Food Council was launched in January 2017.

Efforts continue within the City of Portland to increase food production. In December 2015, zoning amendments were made in the City of Portland Code of Ordinances for Land Use (Chapter 21)22 to allow farmers’ markets to operate two days a week for up to six hours per day on community property, such as the local WIC office.2 Community respondents view Portland as a lab of innovation for the state and for surrounding communities.2 However, they remain concerned about lack of implementation and enforcement of policies.2 A respondent also shared concerns that regulatory processes, such as permitting and licensing, are confusing and that different government branches work in silos, with little information being shared across agencies.23

Food processing is also receiving support in the City of Portland. Supported through US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) funding, the East Bayside neighborhood is experiencing a renaissance spurred by local food manufacturers. East Bayside is home to eight small-scale food manufacturers that are reviving the seaport area. The area is currently zoned as a low-impact industrial zone. In an effort to keep the real estate affordable, the City of Portland zoning ordinance limits retail space in this area, which typically drives up rents, as an accessory use. In the past five years, food manufacturers throughout Cumberland County have increasingly committed to source locally produced foods.15

The school district in the City of Portland is also actively connecting local farmers to (young) consumers. According to the Portland Public Schools Food Service Department, 36% of food served in school meals is sourced locally.24 In 2014, the Portland Public Schools Food Service Director set a goal of spending 50% of the district’s food-procurement dollars on locally sourced foods by the 2016–2017 school year.14

Outside the City of Portland, several town governments are actively supporting local agriculture and consumer food security as well. The town of Cape Elizabeth has an ordinance, passed 40 years ago, that allows farmland taxation at a differential rate compared to other land uses. In 2010, Cape Farm Alliance, a coalition of over 20 viable farms and growing operations based in Cape Elizabeth, brought together community members and farmers to review Cape Elizabeth’s local ordinances and ensure the ordinances support local agriculture. Ordinance revisions were brought to the town board, and many of the suggested revisions were adopted.16 Similarly, the Town of Brunswick established the first chicken ordinance in the state of Maine, which has since been used as a model for similar ordinances throughout the state.7

At the regional level, the Greater Portland Council of Governments (GPCOG) is proactive in developing businesses to support and enhance the local food economy. The council “refashioned [its] whole economic development strategy around food and energy and freight, which build on a number of assets that [are present].”15 In September 2016, the GPCOG was one of 12 US Department of Commerce-designated “Investing in Manufacturing Communities Partnership” regions. The designation will spearhead the proposed Greater Portland Sustainable Food Production Center.

Collectively, as described above, the county, towns, and regional Council of Governments have taken several policy actions to strengthen components of the food system. Yet, there is opportunity to take additional actions to strengthen the food system in a more comprehensive and cross-sectorial manner across the food-supply chain.

Ideas for the Future

Cumberland County has diverse and rich agricultural and fishing sectors as well as an engaged and diverse population.5 Through local government policy efforts, the county has the opportunity to expand and enrich the well-established local food economy and culture while simultaneously supporting the food-insecure and underserved populations. Local stakeholders report interest in such opportunities, including one who noted, “there is a strong desire to understand the sources and where and how food has been produced that people are eating . . . you can see it shaping our economy.”2

Two distinct needs were expressed in many of the stakeholder interviews, both by local government representatives and food-systems stakeholders: the need to build a more efficient local food infrastructure and the need to raise awareness of food insecurities that residents experience throughout the county.

Local food infrastructure is a vital component for connecting producers with consumers. There is significant growth across the country in intermediated markets, which includes food aggregators, processors, and distributors.25 A food-systems stakeholder respondent stated the need for a big push in developing infrastructure that provides “more efficient distribution and delivery systems to strengthen that network.”26 Through policy and public investment, local governments can play a leading role in supporting and bringing locally produced and processed foods into mainstream markets.

A consumer advocate believes that local governments at the county, city, and town levels also have the opportunity to spearhead an asset-mapping project through data collection and analysis to develop “a better understanding in data on the existing assets we have, in terms of the food supply and distribution and related to the mapping of the needs.”4 If capitalized, existing assets could provide further connections between the local food-system infrastructure and consumers by offering easy distribution points. As one food-systems stakeholder respondent stated, “ . . . at the end of the day, 98% of people’s food dollars are still spent in grocery stores . . . So if we really want people to be able to access that, we have to get it to them where they’re currently shopping.”14

The private business sector also has a critical role in building the local food infrastructure. A local government representative pointed to a food hub as a potential example of private-sector engagement.15 The representative noted that it is imperative to draw on the private sector’s business experience, to determine “how to build up the intermediate infrastructure that gets the food from the producers to the institutions and consumers”8 and make such ventures profitable. Partnerships among local governments, private businesses, and non-profit networks have the momentum to connect local producers and consumers and strengthen the Cumberland County food system.

A second important issue is the critical need to raise awareness that food insecurity remains a concern for many county residents.4 Despite having an ingrained “foodie” culture, parts of the county still experience food insecurity. A food-security awareness campaign that highlights the challenges residents face in accessing healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food has the opportunity to lessen the stigma attached to hunger.

On the basis of the broad themes reported in this case study, 11 ideas for simultaneously promoting food security and agricultural viability in Cumberland County are presented below:

- Refocus the Cumberland Food Security Council’s efforts on food-policy advancement, including but not limited to exploring the policy ideas outlined below.

- Ensure health-department regulations support farmers’ markets efforts to donate leftover produce to local food banks (such as Wayside Food Programs and the Good Shepherd Food Bank).

- Explore opportunities for agricultural landowners to pursue purchase of development rights for farmland protection.

- Continue to encourage a discussion of how local ordinances can support farm viability and success.

- Continue to increase the use of local food in the school-district cafeterias through local food-procurement policies.

- Develop educational programs and economic incentives to support small farmers who are interested in moving from direct market to institutional markets.

- Work with Cumberland County farmers’ markets to provide universal acceptance of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)/Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) funds at all farmers markets.

- Build relationships within all local governments to promote public support for comprehensive food policy and planning.

- Invest in intermediate infrastructure of the food system to strengthen stronger connections between area producers/growers and institutions/consumers.

- Facilitate collaborations between affordable housing programs and food-security programs as a way to reduce the double bind of housing and food costs experienced by low-resource families/individuals.

- Encourage homeowners to turn a portion of their yards into a food-donation garden.

Through collaborations and partnerships that exist across the public, private, and civic sectors in Cumberland County and through policy and planning efforts, the community has a unique opportunity to foster a grounded connection between local farmers and consumers in a way that is respectful, equitable, and sustainable for all residents.

Research Methods and Data Sources

Information in this brief is drawn from multiple sources. Quantitative data sources include the 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates and the 2012 US Census of Agriculture. Qualitative data include 15 in-depth interviews with representatives of various sectors of the food system as well as Cumberland County policymakers and staff. Interviewees are not identified by name but are, instead, shown by the sector that they represent, and are interchangeably referred to as interviewees or stakeholders in the brief. Interviews were conducted from April 2015 to September 2015. Qualitative analysis also included a review of the policy and planning documents of Cumberland County, which were reviewed for key policies and laws pertaining to the food system, and a review of the minutes of the Growing Food Connections steering-committee meetings.

Acknowledgements

The GFC team is grateful to the Cumberland County GFC steering committee, Cumberland County government officials and staff, and interview respondents for generously giving their time and energy to this project. The authors thank colleagues at the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab and the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo, Ohio State University, Cultivating Healthy Places, the American Farmland Trust, and the American Planning Association, for their support. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA Award #2012-68004-19894).

Notes

1. United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates, (Washington

DC: United States Census Bureau, 2014).

2. D. Harry, “Portland Drug Addiction Overdose Rates Exceed the Rest of Maine,” Bangor Daily

News, July 28, 2015.

3. Interview with local government representative in Cumberland County (ID 15), 2015.

4. Interview with local government representative in Cumberland County ( ID 23), 2015.

5. Interview with consumer advocate representative in Cumberland County (ID 25), 2015.

6. Interview with extension representative in Cumberland County (ID 100), 2015.

7. University of Maine Cumberland County Cooperative Extension, “Maine Harvest for

Hunger––Cumberland County Food Pantries, Accessed May 10, 2016,

https://extension.umaine.edu/cumberland/programs/horticulture/maine-harvest- for-hunger/food-

pantries/.

8. Interview with local government representative in Cumberland County (ID 13), 2015.

9. Interview with farming and agriculture representative in Cumberland County (ID 26), 2015.

10. Good Shepherd Food Bank, “About Us,” Accessed May 9, 2016, http://www.gsfb.org/about/.

11. Interview with local government representative in Cumberland County (ID 18), 2015.

12. Interview with consumer advocate representative in Cumberland County (ID 27), 2015.

13. Wayside Food Programs, “Food Rescued by Wayside Fills Shelves of Local Pantries,”

Accessed May 10, 2016, http://www.waysidemaine.org/food-rescue.

14. City of Portland, Maine, “Portland, Maine 2016 Minimum Wage,” Accessed May 9, 2016,

http://www.govdocs.com/portland-maine- 2016-minimum- wage/.

15. National Center for Education Statistics, Food Environmental Atlas, (Washington, DC; US

Department of Education, 2012).

16. Interview with consumer advocate representative in Cumberland County (ID 20), 2015.

17. Interview with local government representative in Cumberland County (ID 22), 2015.

18. Interview with farming and agriculture representative in Cumberland County (ID 19), 2015.

19. National Agricultural Statistics Service, Census of Agriculture County Summary Highlights,

(Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, 2012).

20. W. Becker, Growing Food Connections Community of Opportunity Background Check:

Cumberland, Maine, (Buffalo: University at Buffalo, 2015).

21. National Agricultural Statistics Service, Census of Agriculture Selected Operation and

Operator Characteristics: 2012 and 2007, (Washington, DC: United States Department of

Agriculture, 2012).

22. Tall Ships Portland, “Maine’s Lobster Industry: A Look at Maine’s Famous Seafood,” Tall

Ships Portland, vol 2016, (Portland, Maine, 2015).

23. United States Census Bureau, Census of Governments: Local Governments in Individual

County-Type Areas, (Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau, 2012).

24. Greater Portland Council of Governments, Greater Portland Council of Governments

Homepage, Accessed May 10, 2016, http://www.gpcog.org/.

25. City of Portland, Maine, Code of Ordinances, (Portland: City of Portland, 2014).

26. Interview with retail representative in Cumberland County (ID 21), 2015.

27. Portland Public Schools, “Our Most Frequently Asked Questions,” Accessed May 13, 2016,

http://www.portlandschools.org/departments/food_service/faq/.

28. A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Food Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution: Local

Governments’ Roles in Supporting Food System Infrastructure,” Planning and Policy Briefs,

(Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project, forthcoming).

29. Port of Portland, Port of Portland Marine Terminal Statistics 1984-2014, Accessed

November 20, 2016,

https://www.portofportland.com/SelfPost/A_201511616535AnnualHistoryfrom1978web.pdf.

30. Maine Department of Labor, Center for Workforce Research and Information, Civilian Labor

Force Estimates, Monthly Seasonally Adjusted Metropolitan Area Estimates, Portland-South

Portland, Accessed November 20, 2016, http://www.maine.gov/labor/cwri/laus.html.

Community of Opportunity Feature

AUTHORS

Jeanne Leccese, University at Buffalo Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

CONTRIBUTORS

Jill Clark, Ohio State University

Julia Freedgood, American Farmland TrustKimberley Hodgson, Cultivating Healthy PlacesSubhashni Raj, University at Buffalo

SERIES EDITOR

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

DESIGN, PRODUCTION and MAPS

Samantha Bulkilvish, University at BuffaloKelley Mosher, University at BuffaloClancy Grace O’Connor, University at Buffalo Brenda Stynes, University at Buffalo

COPY EDITOR

Ashleigh Imus, Ithaca, New York

Recommended citation: Leccese, Jeanne, and Samina Raja. “Building on the Strengths of Land and Sea: Policy opportunities for Strengthening the Food System in Cumberland County, Maine.”In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited bySamina Raja, 9 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project, 2017.