Print Version (PDF)

Towards Health Equity in the Heartland: Advancing Community-Led Food Planning in Douglas County, Nebraska

In March 2015, Douglas County, Nebraska was selected as one of eight Communities of Opportunity (COOs) in the country that have significant potential to strengthen ties between small- and medium-sized farmers and residents with limited food access.1 Working with the Growing Food Connections (GFC) project team, county stakeholders have since established a steering committee that has charted a vision for the future of Douglas’s food system.2

This brief, which draws on interviews with Douglas County stakeholders and secondary data sources, provides information about local government policy opportunities and challenges in the food system to inform the work of the GFC steering committee and stakeholders in Douglas County.

Background

Big Muddy Farms, an urban farm in a residential community in northern Omaha. Image Source: Nati Harnik/AP

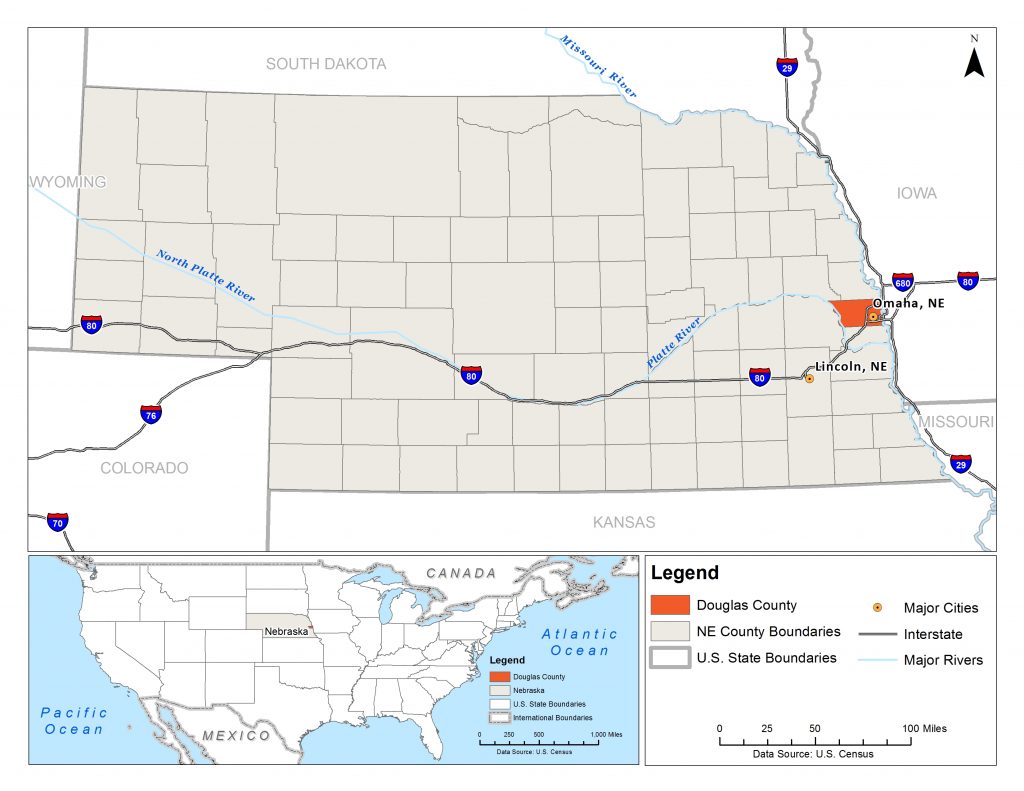

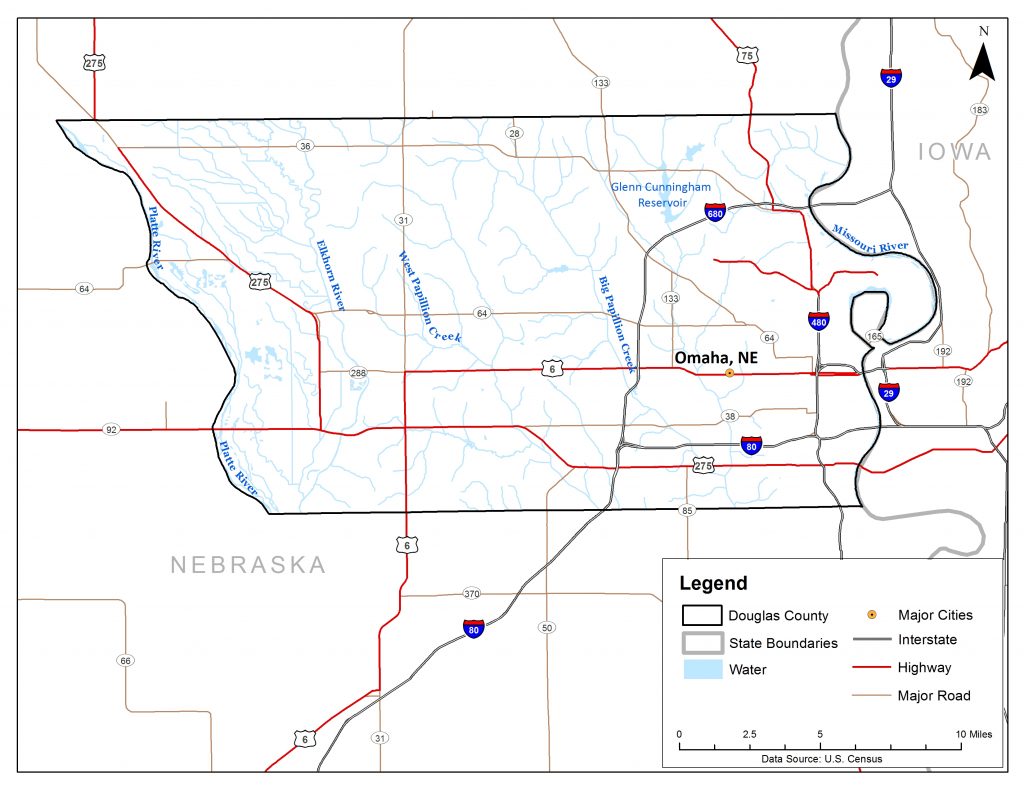

Douglas County is located along the Missouri River on the eastern edge of the state of Nebraska. With just over 543,000 residents, Douglas is Nebraska’s most populous county and home to over one-fourth of the state’s residents.3 The county seat is the City of Omaha, which is home to 82% of the county’s residents.3 The county also contains several smaller incorporated municipalities and unincorporated areas.4 Although characterized as urban, the county benefits from its proximity to productive and valuable farmland, clean air and high quality water sources, and good access to green space and parks. Perhaps most characteristic of the county is its reputation as a great place to raise a family. Omaha’s location at the heart of the country has earned the city a reputation as a flyover city, but residents know there is more to this metro area than most outsiders realize. It is a region that celebrates and treasures the past, while also warmly embracing change and growth. The metro area renowned for TV dinners from major food manufacturers such as Kellogg’s and Tyson Foods now houses a budding upscale restaurant scene. While ranchers continue to raise cattle on the sprawling prairies surrounding the region, Omaha has begun to attract new types of businesses and interest in urban agriculture.

With 443,000 residents living in a land area of 127 square miles, Omaha is the state’s largest city, but has a distinctive small-town feel, with a common refrain being that you can travel anywhere within the city in 20 minutes.3, 5 The city is also highly regarded for its overall low unemployment (5%) and relative economic stability.3 With a median household income of nearly $51,000, many residents view the city as offering an affordable, high quality of life.3 According to a 2013 analysis, Omaha has the most Fortune 500 companies, per capita, of any major metro area in the country (although in 2015, Con-Agra announced that it was relocating its headquarters to Chicago).6 However, the level of overall wealth in the city masks deep inequality and poverty, as nearly 1 in 5 residents (16%) live in poverty.3

While the county has a strong, diverse regional economy that affords many residents a high quality of life, significant disparities exist and threaten future vitality. The county has relatively high levels of racial segregation and concentrated poverty. The neighborhoods with the highest Black and Latino populations generally have lower access to opportunity for jobs, lower labor market engagement, and increased potential for exposure to health hazards. Demographic shifts offer challenges and opportunities for creating a more equitable and inclusive region. While the population of Omaha, like Douglas County overall, is majority White (67%), its Black (13%) and Latino (14%) communities are increasing.3 Stakeholders described how the city’s 72nd Street serves as a dividing line between the affluent and predominantly White neighborhoods of West Omaha, and the low-income, minority neighborhoods of East Omaha.7 Northeast Omaha is home to a predominantly Black and poor population, but is beginning to experience some redevelopment after decades of disinvestment. However, entrenched challenges of poverty, unemployment, low educational attainment, and crime continue to persist. Southeast Omaha also faces many economic challenges and is home to the city’s growing immigrant population. The area is predominantly Latino, but has welcomed refugees from Myanmar (formerly Burma), Sudan and other countries in recent years.8

Despite deep-rooted challenges of inequality and poverty, many individuals and organizations in Omaha and Douglas County envision opportunities to create an equitable region in which all residents can thrive. Over the last fifteen years, the local community has begun making connections between poverty, food insecurity, and health, prompting conversations and initiatives to combat hunger, increase local food production, and educate residents about healthy eating.

Douglas County is located along the Missouri River on the eastern edge of Nebraska. Image Source: Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab

Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities

Douglas County is a rich agricultural community increasingly filled with a variety of farming options and food systems stakeholders, from large factory farms and agricultural corporations to community gardens, small organic farms, aquaponics and local food movements. A county government official described the city of Omaha and several smaller incorporated municipalities as comprising a large metropolitan area that is surrounded by farmland, some of which has been lost to development over the last several decades.7 There are nearly 400 farms in Douglas County comprising over 86,000 acres.9 The average farm size is 217 acres, but more than half of the county’s farms (about 230 farms) are less than 50 acres in size.9 Most farmland (88.5%) is crop farmland for corn, soybeans, and cattle characteristic of industrial agriculture, but a small portion is food-producing farmland.9 While the average market value of products sold per farm is $146,513, the majority of farms (285 farms) earn less than $50,000 in sales and a quarter of the county’s farms (99 farms) earn less than $1,000 in sales.9 In other words, many of the county’s farms are small and struggle to earn a profit.

Challenges

There are significant challenges to enhancing agricultural viability in Douglas County. An inadequate labor supply and insufficient aggregation and distribution infrastructure pose challenges for small farmers looking to scale up production and connect to underserved consumers. Stakeholders that work closely with farmers through Extension or in the aggregation sector repeatedly emphasized labor as the greatest challenge facing farmers in the county, explaining that attracting labor to farms is difficult given the region’s short growing season and very low unemployment rates.10-11 Chronic labor shortages limit production and contribute to the predominance of row crop production over much more labor-intensive fruit and vegetable production in the county.11 While the region has a lot of processing infrastructure, infrastructure for small-scale and local producers is lacking.2 In addition to infrastructure, training and certification is required for growers in order to meet the supply needs of large institutional buyers and retailers.

Key challenges for urban agriculture are access to lots, access to water, and long-term leases. While there are many vacant lots in the city that could potentially be utilized for small-scale food production, and there are also underserved areas that could benefit from access to fresh food, some areas of eastern Omaha are designated a superfund site due to lead contamination and require cleanup in order to be viable for agriculture.12 Additionally, a local government representative expressed constraints as a result of state legislation that does not allow land bank lots to be used for agricultural purposes.12 Furthermore, stakeholders across various sectors asserted that it is very expensive to put water on a vacant lot, and growers share concerns that once equipped with water, these lots will increase in property value and become vulnerable to development pressure.13 These concerns are heightened by the short-team leasing options for use of many of these lots (usually one year) which threaten sustainability.13

Opportunities

Opportunities for direct sales and marketing of local agricultural products in the county exist and are gaining popularity in recent years, with many farmers selling directly to consumers through farmers’ markets, farm stands, community-supported agriculture (CSA), and online through Nebraska Food Co-Op, and these opportunities appear to be expanding. According to a food aggregation representative, in 2008, the concept of a CSA was largely unheard of in Douglas County.11 Today, Tomato Tomato operates a 1,000-member CSA and coordinates delivery of shares with local grocery store Hy-Vee and is working with store produce managers to sell local produce within the stores.11 There are also many farmers’ markets within Omaha, from the large non-profit Omaha Farmers Market to Benson Farmers Market, a small non-profit market that has hosted vendors who have gone on to have their products sold in local chain stores.14

Some stakeholders noted that many small-scale farmers, ranchers, and gardeners are interested in moving away from direct sales and would like to serve local markets via food retailers and other food distributors.15 New business models and partnerships geared towards helping local farmers sell their produce to local retailers and other distributors could support rural-urban partnerships for improving farm viability and food security. There are many promising examples in the county. There is a thriving restaurant scene in Omaha and a number of restaurants that source locally.2 The city is also home to a handful of major corporations with cafeterias that purchase large quantities of food, some of which are sourcing locally.2 Innovative partnerships between farmers and other institutions such as schools, neighborhood stores, and food banks can play a role in connecting low-income residents to local fresh foods. There is also growing consumer demand for organic, free-range, and non-GMO (genetically modified organisms) products. Currently, these imported products represent a multi-million dollar annual loss to the local food economy. There is opportunity to build a more sustainable community food system by capturing and satisfying some of this demand through local food retailers. This would require the development of local food infrastructure at a sufficient scale so that local food producers could compete with imported, high-value foods. As previously mentioned, Tomato Tomato demonstrates the increasing interest in the development of local food infrastructure for small-scale local producers. Furthermore, partnerships will be most effective in the context of planning and policy interventions that create a strong regulatory environment and incentive structure for producing and purchasing locally.

There is also growing interest in food production within the metro area. There are several urban farms in Omaha and residents have expressed interest in using vacant lots for community gardening. The non-profit organization Whispering Roots operates aquaponics, hydroponics, and urban farming programs in socially and economically disadvantaged communities in the city.5 Whispering Roots is also working towards increasing farmer ownership and job creation in local processing and distribution sectors.15 Some stakeholders point to the work of Whispering Roots as a strong example of how community food systems offer important economic development and environmental sustainability opportunities for communities.15

Food Security: Challenges and Opportunities

The City of Omaha is the largest city in the state and the county seat. Image Source: Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab

Food security is a serious issue throughout the City of Omaha and Douglas County, but some areas and populations are more vulnerable than others. Despite relatively higher rates of food production, access to healthy foods is an issue in rural areas of Douglas County. While some stakeholders stated that there are pockets of poverty and food insecurity throughout all parts of Omaha, nearly all respondents asserted that food insecurity is heavily concentrated in areas with greater proportions of low-income residents and people of color, including North Omaha and South Omaha.16 Some stakeholders suggested that the cost of food, especially healthy food, is relatively high for most of the city’s residents.17 Nearly 13% of households in the city receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.3

Challenges

Challenges to food security in Douglas County go beyond poverty and economic access and include lack of physical access to both traditional and newer forms of food retail outlets due to location and transportation constraints. The Douglas County Health Department has mapped grocery stores in the county, and while stores carrying food are well distributed throughout the county, these stores often take form of the gas stations and convenience stores lower-income neighborhoods throughout the county, which tend to have less variety and less healthy food options. For example, North Omaha contains many more convenience stores than fully stocked grocery stores. While there is also a relative lack of grocery stores in South Omaha, the sizable Latino community operates some independently owned markets.18 There are a number of farmers’ markets throughout the city, most of which accept EBT, yet the locations of these markets are not necessarily in high-need areas.18 Transportation is a key barrier to food access for individuals who do not have access to a vehicles.5 There is no light rail system, and bus service is limited and routes do not align well with the locations of food retail outlets.17

Opportunities

There are institutions and programs in place that help provide some relief from hunger and food insecurity in Douglas County. The county has an emergency food system comprised of the Food Bank of the Heartland and numerous food pantries.16 During the 2015-2016 school year, nearly three-quarters of students (74.3%) in Omaha Public Schools were eligible for free and reduced-price lunch.19 This percentage represents a 20.1 percentage point increase over the last 14 years.19 As the largest school district in the city (and county) which serves most of its low-income neighborhoods, Omaha Public Schools offers free breakfast to all students, and there have been efforts in recent years by local non-profits to promote school breakfast and ensure that after school programs serve snacks and dinner.12 However, there is a need to increase healthy food access in schools and childcare centers.12 While there is some small-scale repurposing of food waste and a handful of efforts to redistribute food to those in need (including one major food bank), the vast majority of food waste in the county goes to landfills.7

There is a growing body of stakeholders in Douglas County committed to improving food security and efforts so far have yielded key partnerships, programs, and possibilities. North Omaha has been the geographic focus of many initiatives to improve food security. The 2007 North Omaha Development Project plan identified attraction of a large grocery store as a key goal of the plan and conducted an analysis of existing store locations, sales volume, and consumer demand for food retail.20 As a result of the plan, the neighborhood gained a grocery store and local government leaders gained understanding of the food security challenges of low-income residents, which has prompted local government support of other food access initiatives.21 The plan also provided information for the Douglas County Health Department in designing its Healthy Neighborhood Store project.21 The project operates in 13 existing corner stores in the city’s lowest income and most food insecure neighborhoods and has worked with store owners to increase the stock of healthy foods in their stores.21 The project has also worked to ensure that these stores accept public assistance benefits.21 Currently, the project is working to connect store owners with local farmers to support the viability of small producers while improving healthy food access.21 Underserved consumers are also being connected to local farmers through Tomato Tomato, a local 1,000-member community-supported agriculture (CSA), which partners with No More Empty Pots, Cooking Matters, and other local non-profits to set aside shares for low-income residents and offer educational programming on preparing healthy meals.11

Several programs have also promoted local food production within city limits to address food insecurity. City Sprouts operates a community garden and urban farm in North Omaha and allows individuals and organizations to rent raised beds to grow food for personal consumption.13 About 40 families rent gardens, half of which are from the immediate neighborhood.13 Additionally, several organizations that work with individuals with disabilities rent gardens.13 City Sprouts also operates a paid internship program exclusively for low-income youth in the neighborhood to learn how to grow and harvest produce and to sell their produce on site in a weekly farm stand.13 These programs are some of the examples of urban agriculture activities in the city of Omaha that are connecting food access challenges related to poverty with the city’s food production potential.

Local Government Public-Policy Environment

Fresh fruit and vegetable display in one of Douglas County Health Department’s Healthy Neighborhood Stores. Image Source: OmahaDigest

The key food security challenges in Douglas County are to increase food access for the county’s low-income residents and communities of color in both urban and rural areas. African American and Latino communities in East Omaha are especially vulnerable to hunger and food insecurity and face many barriers to food access because of segregation and disinvestment. The key food production challenges in Douglas County are to provide support for small and mid-sized farmers in the county to remain economically viable and scale up production. While a stable supply of labor appears to be the primary concern for growers in areas outside municipalities, access to water appears to be the main concern for growers in urban areas. The work of food systems stakeholders over the last few years has fostered many partnerships and demonstrated the community interest in understanding the various food systems challenges and opportunities in Douglas County.

Community-Led Food Planning

In a state dominated by big agriculture, some food systems stakeholders worry that the policy environment is not responsive to the interests of small and mid-sized farmers.11 Moreover, many respondents stressed that agriculture and food tend to be overshadowed by other pressing public concerns, particularly violence and crime.12 Furthermore, according to stakeholders, the political and cultural climate of the state emphasizes bottom-up approaches to addressing issues rather than top-down approaches and strongly values collaboration.12 This emphasis on community-led solutions has resulted in a tremendous amount of conversation and activity around food systems challenges in Douglas County in a short period of time, mostly led by grassroots community-based organizations and non-profits. While there are several strong, small networks of food systems stakeholders in the county, a larger, more coordinated network where stakeholders can more fully share resources does not exist, and local government has largely been absent from conversation and activity. Furthermore, the overlap of the work of different food systems stakeholders, largely grant-funded community-based organizations and non-profits, sometimes leads to competition rather than collaboration among stakeholders. The Metro Omaha Food Policy Council was established in 2011 to encourage cooperation among stakeholders, but has undergone several structural changes.17 In order to realize the potential of emerging partnerships and programs, greater local government resources need to be invested in the work.

Municipal Support for Urban Agriculture

In recent years, municipal government has increasingly been responsive to community food production initiatives. The process has been slow but there has been demonstrable progress over time, particularly with the previous mayoral administration of Jim Suttle (2009-2013). The City of Omaha is increasingly concerned with healthy environments and, in 2015, Mayor Jean Stothert established a new Active Living Advisory Committee.22 The city has also incorporated health promotion into the plans and initiatives of several departments. The Environment Element of the Omaha Master Plan created in 2008 has a “Community Health” section that discusses the possibilities of green spaces and open spaces for urban agricultural uses.23 The planning process involved several food systems stakeholders who helped the city establish a working definition of community gardens.21 The Transportation Element of the Omaha Master Plan also promotes planning for healthier communities.24 A recent update to the city park plan also identified park land that could be used for agriculture. The Adams Park Health Impact Assessment (HIA), the first HIA undertaken in Nebraska and the Great Plains region of the country, called for urban farming and community gardening activities at the heart of the North Omaha Park.25 Groups have also been working with the city around their policies around gardening and open space. In 2013, the city planning department identified select parcels and put out a request for proposal (RFP) for those parcels and allowed organizations to come in and on identified lots start gardens on short-term leases as part of rehabilitation programs for neighborhoods.21 In 2015, the City of Omaha released a vacant lot toolkit to provide examples of uses for vacant lots (including urban agriculture) and steps to improve vacant lots.26 But overall, urban agriculture is relatively new to the area and local government lacks technical expertise in this area to develop and implement policy. Extension could potentially serve in an advisory capacity on developing policy around urban agriculture, but needs to develop a stronger presence in the local community.

At the county level, Douglas County is in the process of updating its comprehensive land use plan and zoning regulations. The existing documents, last updated in 2006, do not address topics of urban agriculture and community food production. In the update process, the county through its contracted planning consultant, has interviewed a variety of local stakeholders including some directly connected with the local food movement and the Growing Food Connections steering committee.27 It is anticipated that Douglas County’s updated comprehensive plan and zoning regulations will contain policy sections on how urban agriculture and community food production can fit within the county, including definitions, use types, and other guidelines that will facilitate these land uses in Douglas County.27

Local and Regional Planning for Public Health

Municipal plans and programs have also addressed food access issues and planning work at the regional level has identified key policies and infrastructure for sustainable food production. As previously mentioned, the 2007 North Omaha Development Project included incentives for grocery store attraction and prompted discussion of the importance of food retail outlets and food access in underserved areas of the city.20 The plan also helped to demonstrate the relevance of food systems issues to city officials, and increased municipal support for several food systems initiatives of the Douglas County Health Department in the city. The Health Department is increasingly focused on health promotion and the prevention of obesity and chronic diseases through a food and nutrition lens as well as a concomitant focus on health equity, and has received several major grants to work with local communities around food access and affordability.21 The Health Department’s Healthy Neighborhood Store program has brought attention to the lack of healthy food access in underserved areas of the city.21 At the regional level, the eight-county regional planning organization Metropolitan Area Planning Agency (MAPA)’s 2014 Heartland 2050 Vision plan touches on urban agriculture and food hubs, as well as growth management and preservation of farmland in the rural areas outside of incorporated municipalities in Douglas and surrounding counties.28 MAPA, in partnership with local organizations, is also exploring opportunities to redistribute or compost food waste in the context of its solid waste management plan.29

Local government is increasingly concerned with healthy environments and this concern has translated into a number of planning and programming initiatives. Over the last 10 years, there has also been increasing commitment from local government to distributing resources and investments across all parts of the city of Omaha. City leadership, including planning leadership, recognizes the economic and social challenges facing the eastern areas of the city, including food insecurity. The 75 North redevelopment project in North Omaha, founded in 2011, has plans to include gardening and indoor food growing components and represents collaboration between various organizations.8 Although the city will likely not contribute direct funding to the project, it is completing a number of public improvements to support the project.8 These broad trends in health and equity offer opportunities for local government to engage in food systems planning to support and extend the ongoing efforts of community organizations.

State Enabling Legislation

Although planning occurs at the local and regional levels, many stakeholders identified state government as a key policy arena for local food systems issues, perhaps due to state legislation in recent years that has had important impacts on connecting farmers to underserved consumers. In 2010, the state legislature passed Legislative Bill 986, which authorizes grants to be used to purchase EBT machines at farmers’ markets, and for marketing, promotion and outreach activities related to federally subsidized food and nutrition programs at farmers’ markets.30 There is also a bill in the state legislature that would allow for the preparation of value-added products in non-commercial kitchens, which would reduce a significant barrier to entry for food businesses.21 State legislators have also met with community groups to discuss urban agriculture and community gardening issues.5 While the state level may not be the most effective level to enact a robust set of plans and policies for the community food system in Douglas County, the efforts made by state government officials to become engaged in food systems issues provide good models for local government officials looking to become more involved in the food system and underscore the role of policy in bringing about sustainable change.

Corporate Power in the Food System

Finally, it is important to impart historical background on the larger context of corporate consolidation and control in the United States and globally that shapes inequities within the local food system and may constrain local government public policy. In particular, the control of political and economic systems by corporations in order to influence trade regulations, tax rates, and wealth distribution, among other measures, shapes inequities within the local food system experienced by struggling farmers and vulnerable consumers. These structural forces are particularly evident in a region dominated by large-scale industrial agriculture. A farming and agriculture representative emphasized the role of corporate influence in how food is produced, processed, distributed, and consumed in the region, describing long-term trends: “to abandon diversified agriculture in favor of continuous grain production and large-scale confinement feeding of livestock and poultry; the resulting and inevitable elimination of farm profits and free cash among local and regional diversified (sustainable) producers; and poverty-level wages at all levels of food production, processing and distribution.”15 Within this larger context, while segregation and disinvestment are part of the foundation underpinning long-term food insecurity and limited access for Black and Latino communities in Omaha and Douglas County, less visible and slow-moving structural changes in the agricultural industry have also eliminated the meat, milk and food grain products once produced for local and regional consumption in the Missouri Valley.15 This food production and related processing operations have moved to the Southwest United States where the costs of land, water, and labor are lower.15 Given this larger context of corporate influence, some stakeholders observed that local government may not be the right scale for policies that address the structural causes of agricultural viability and food insecurity in the county.

Ideas for the Future

Over the last several years, residents and organizations in Douglas County have been working in partnership to diversify and sustain the county’s strong tradition of agriculture, with growing interests in urban agriculture, farmers’ markets, and community-supported agriculture. Many stakeholders also recognize the potential to connect local food production to combat local hunger and food insecurity and have developed initiatives towards these aims. At the same time, local government has demonstrated increasing interest in health promotion and redevelopment of distressed areas through plans and programs. Through strengthened partnerships and coordination between local government and food systems stakeholders, Douglas County is well positioned to increase community food production and food security for a healthier and equitable future. Below are several suggestions to help move food policy forward systematically and strategically in Douglas County.

Make Food Access a Priority in Redevelopment Projects

There are many opportunities for local government to further support the efforts of local organizations working to alleviate food insecurity. Local government should continue to spearhead and support redevelopment projects in the most underserved areas of the city given that many food access challenges residents in these areas face are tied to poverty and disinvestment. Local government should also incorporate a variety of specific strategies aimed at increasing access to fresh, nutritious foods in redevelopment projects. Some strategies such as attracting grocery stores in underserved neighborhoods and increasing the stock of fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods at neighborhood corner stores are already underway. Additional strategies might include supporting or developing other retail outlets such as farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture programs, and mobile vendors and improving public transportation to grocery stores and farmers’ markets. Additionally, incentivizing the use of SNAP dollars at these local markets can support local agriculture while also addressing inadequate food access in the county. Local governments can use public financing tools to incentivize similar initiatives. Examples already exist in places like Douglas County, Kansas that may prove useful to Douglas County in their efforts to strengthen the community food system.31 The policy brief Incentivizing the Sale of Healthy and Local Food details the experience of other communities across the country such as Baltimore, Maryland, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Washington D.C. that may be helpful as Douglas considers next steps.32

Scale Up Support for Urban Agriculture

There are also significant opportunities for local government planning and policy to promote local food production, particularly within urban areas. Some urban areas that could benefit from agricultural activities are under-utilized due to soil contamination. Local government has data on superfund sites that could help guide and inform soil cleanup efforts.8 In addition to soil cleanup efforts on contaminated vacant lots, the city should also develop water access policies for vacant lots and other properties for urban agricultural uses, and ensure the sustainability of community gardening and other urban agriculture activities through long-term leases and other legal protections from development pressure. A number of local governments from across the country have taken a whole host of actions to support urban (and other forms of) community food production including by creating and implementing agricultural plans (Marquette County, Michigan); using public lands for food production (Lawrence, Kansas); and supporting new farmer training and development (Cabarrus County, North Carolina).33 The city and county governments of Omaha and Douglas can leverage their communities’ assets and knowledge to create a supportive policy environment for community food producers.

Reduce Regulatory Barriers to Direct Sales of Agricultural Products

In order to promote the economic viability of agricultural activities, local government should enact policies to reduce barriers to commercial sale of locally produced and value-added products, for example, by revising limitations on the commercial sale of produce in residentially zoned areas, and amending requirements for value-added products to be prepared in commercial kitchens. Local government can also take steps to make the development process for urban agriculture more transparent and convenient for residents. Currently, zoning, licensing and permits are spread across multiple city departments.14 There is a lack of public information about the steps of the development process, required applications and fees, and appropriate departments to contact for inquiries.14 Local government could make this process more transparent and efficient by designating a department or creating a centralized office to be responsible for urban agriculture activities. By centralizing and streamlining these requirements under the responsibilities of one staff position or department, it could also help identify and revise requirements and costs that create unnecessary barriers for growers and vendors.

Leverage Institutional Purchasing Power to Expand Markets for Farmers

While Douglas County has a number of farmers’ markets and other venues for small farmers to sell directly to consumers, many farmers are interested in the power of institutional purchasing. A variety of public and private institutions throughout the county prepare, cook, and serve meals every day, including schools, universities, hospitals, prisons, corporate cafeterias, and senior care facilities. There are many ways that local governments can facilitate connections between small farmers and local institutions (as well as local food retailers). Leveraging institutional purchasing power can also expand access to healthy food for vulnerable consumers—consumers who are also clients, employees, and students in institutions throughout the county. The policy brief Local, Healthy Food Procurement Policies focuses on the ways that local government agencies such as public school districts, correctional facilities, and public hospitals can purchase, provide, or make available produced by local farmers.34

Invest in Food Infrastructure Development and Enhancement

Several stakeholders emphasized infrastructure development and enhancement as essential to helping small farmers achieve sufficient scale to tap into larger and more diverse markets. Related to food infrastructure development are the related steps of food aggregation, processing, and distribution. These steps are vital in diversifying and growing the ways that small and mid-sized farmers and food businesses can reach consumers, filling gaps in the current food distribution system to meet demand for local, sustainably produced products and allowing local producers to meet the rapidly changing demands of local food markets. Food aggregation, processing, and distribution infrastructure can take a variety of forms, all of which have policy, regulatory, programmatic and funding implications. An important first step for Douglas County may be assessing the current state of its complete food system, including the presence (or absence) of local and regional supply chain infrastructure. For example, local governments across the country, including the City of San Francisco, California and Lawrence-Douglas County, Kansas, have developed food infrastructure assessments and feasibility studies.35

Provide Support for Capacity Building of Food Policy Council

The Douglas County Growing Food Connections Steering Committee has worked with the GFC team of researchers and technical assistance providers to identify local policy opportunities and barriers to achieve food systems goals. There is interest among steering committee members and other stakeholders to continue this capacity-building process beyond the Growing Food Connections project and create a long-term vehicle for initiating and maintaining this process over time. One opportunity to leverage and build the capacity of the Metro Omaha Food Policy Council to serve as a vehicle for engaging local government officials, economic development specialists, and local food leaders alongside local farmers, ranchers, food system workers, and vulnerable consumers to understand and implement public policies that advance a shared vision for food system sustainability. There is a particular interest among respondents in tying discussions of the community food system more closely to issues of economic development and environmental sustainability. The Growing Food Connections Local Government Policy Database provides examples of food system plans and policies developed by local governments across the country. Policies span different geographic regions, sizes of government, rural and urban contexts, and public issues—illustrating the wide range of priorities and approaches Douglas can take to advance food systems work.36

Research Methods and Data Sources

Information in this brief comes from multiple sources. Quantitative data sources include the 2012- 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates and the 2012 Census of Agriculture, as well as datasets from state education and public health departments. Qualitative data include 15 in-depth interviews with representatives of various sectors of the food system as well as City of Omaha and Douglas County policymakers and staff. Interviewees are not identified by name but are, instead, shown by the sector that they represent, and are interchangeably referred to as respondents, interviewees or stakeholders in this brief. Interviews were conducted from April to September 2015. Qualitative analysis also includes a review of policy and planning documents of Douglas County, which were reviewed for key policies and laws pertaining to the food system, and a review of the minutes of the Growing Food Connections steering committee meetings. A draft of this brief was reviewed by interview respondents and community stakeholders prior to publication.

Acknowledgments

The GFC team is grateful to the Douglas County GFC steering committee, Douglas County government officials and staff, and the interview respondents, for generously giving their time and energy to this project. The authors thank colleagues at the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab and the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo, The Ohio State University, Cultivating Healthy Places, American Farmland Trust, and the American Planning Association for their support. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA Award #2012-68004- 19894), and the 3E grant for Built Environment, Health Behaviors, and Health Outcomes from the University at Buffalo.

Notes

1 Growing Food Connections, “Eight ‘Communities of Opportunity’ Will Strengthen Links between Farmers and Consumers: Growing Food Connections Announces Communities from New Mexico to Maine,” March 2, 2015, http://growingfoodconnections.org/news-item/eight-communities-of-opportunity-will-strengthen-links-between-farmers-and-consumers-growing-food-connections-announces-communities-from-new-mexico-to-maine/.

2 Growing Food Connections, “Douglas County, Nebraska: Community Profile,” May 12, 2016, growingfoodconnections.org/research/communities-of-opportunity.

3 U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, 2012-2016 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2016).

4 U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 Census of Governments: Organization Component Estimates (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012).

5 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Douglas County (ID 66), July 28, 2015.

6 H.J. Cordes, “Omaha’s ‘Fab Five’ of Fortune 500 Firms Stand Tall,” Omaha World-Herald, February 3, 2013, https://www.omaha.com/money/omaha-s-fab-five-of-fortune-firms-stand-tall/article_610299a5-f03a-5ebc-b7ce-74688dd35ecc.html#omaha-s-fab-five-of-fortune-500-firms-stand-tall.

7 Interview with Local Government Representative in Douglas County (ID 56), June 10, 2015.

8 Interview with Local Government Representative in Douglas County (ID 64), July 30, 2015.

9 U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012 Census of Agriculture (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

10 Interview with Cooperative Extension Representative in Douglas County (ID 57), August 4, 2015.

11 Interview with Food Aggregation Representative in Douglas County (ID 58), June 9, 2015.

12 Interview with Local Government Representative in Douglas County (ID 54a), April 14, 2015.

13 Interview with Farming and Agriculture Representative in Douglas County (ID 65), June 8, 2015.

14 Interview with Food Retail Representative in Douglas County (ID 55), June 8, 2015.

15 Farming and Agriculture Representative, email to author, June 26, 2017.

16 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Douglas County (ID 60), June 8, 2015.

17 Interview with Local Government Representative in Douglas County (ID 61), July 3, 2015.

18 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Douglas County (ID 63), June 8, 2015.

19 Omaha Public Schools, 2015-16 District Free and Reduced-Price Lunch Program, December 22, 2015, https://district.ops.org/DesktopModules/Evotiva-UserFiles/API/FileActionsServices/DownloadFile?ItemId=288612&ModuleId=8790&TabId=2338.

20 North Omaha Development Project Steering Committee, The North Omaha Development Project: A Strategy for Community Investment (Omaha, NE: City of Omaha Planning Department, 2007).

21 Interview with Local Government Representative in Douglas County (ID 54b), June 8, 2015.

22 J. Stothert, Executive Order No. S-27-14: Establishment of Mayor’s Active Living Advisory Committee (Omaha, NE: Mayor’s Office of the City of Omaha, 2014).

23 City of Omaha Planning Department, Omaha Master Plan – Environment Element (Omaha, NE: City of Omaha Planning Department, 2008.

24 City of Omaha Planning Department, Omaha Master Plan – Transportation Element (Omaha, NE: City of Omaha Planning Department, 2008.

25 Douglas County Health Department, Adams Park Health Impact Assessment (Omaha, NE: Douglas County Health Department, 2012).

26 City of Omaha Planning Department, Omaha’s Vacant Lot Toolkit (Omaha, NE: City of Omaha Planning Department, 2015).

27 Local Government Representative, email to author, June 26, 2017.

28 Metropolitan Area Planning Agency, Heartland 2050 Vision (Omaha, NE: Metropolitan Area Planning Agency, 2014).

29 Metropolitan Area Planning Agency, Integrated Solid Waste Management Plan Update (Omaha, NE: Metropolitan Area Planning Agency, 2012).

30 Nebraska Legislature, Legislative Bill 986 (Omaha, NE: Nebraska Legislature, 2010).

32 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Incentivizing the Sale of Healthy and Local Food,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCHealthyFoodIncentivesPlanningPolicyBrief_2016Feb-1.pdf.

33 A. Dillemuth, “Community Food Production: The Role of Local Governments in Increasing Community Food Production for Local Markets,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2017), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCFoodProductionPlanningPolicyBrief_2017August29.pdf.

34 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Local, Healthy Food Procurement Policies,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2015), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/FINAL_GFCFoodProcurementPoliciesBrief-1.pdf.

35 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Food Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCFoodInfrastructurePlanningPolicyBrief_2016Sep22-3.pdf.

36 S. Raja, J. Clark, J. Freedgood, and K. Hodgson, Growing Food Connections: Local Government Food Policy Database (Buffalo, NY: University at Buffalo, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/tools-resources/policy-database/.

Community of Opportunity Feature

AUTHORS

Enjoli Hall, University at Buffalo

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

CONTRIBUTORS

Jill Clark, The Ohio State University

Julia Freedgood, American Farmland Trust

Kimberley Hodgson, Cultivating Healthy Places

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

SERIES EDITOR

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

PROJECT COORDINATOR

Enjoli Hall, University at Buffalo

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Brenda Stynes, University at Buffalo

Daniela Leon, University at Buffalo

Samantha Bulkilvish, University at Buffalo

Clancy Grace O’Connor, University at Buffalo

Recommended citation: Hall, Enjoli and Samina Raja. “Towards Health Equity in the Heartland: Advancing Community-Led Food Planning in Douglas County, Nebraska.” In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited by Samina Raja, 10 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project, 2018.