Print Version (PDF)

Supporting the Chile Capital of the Southwest: The Role of Local Government in Sustaining Farming Traditions in Luna County, New Mexico

In March 2015, Luna County, New Mexico was selected as one of eight Communities of Opportunity (COOs) in the country with significant potential to strengthen ties between small- and medium-sized farmers and residents with limited food access.1 Working with the Growing Food Connections (GFC) project team, county stakeholders have since established a steering committee that has charted a vision for the future of Luna’s food system.2

This brief, which draws on interviews with Luna County stakeholders and secondary data sources, provides information about local government-policy opportunities and challenges in the food system to inform the work of the GFC steering committee and stakeholders in Luna County.

Background

Chile pepper farm in the City of Deming in Luna County, New Mexico. Image Source: American Farmland Trust

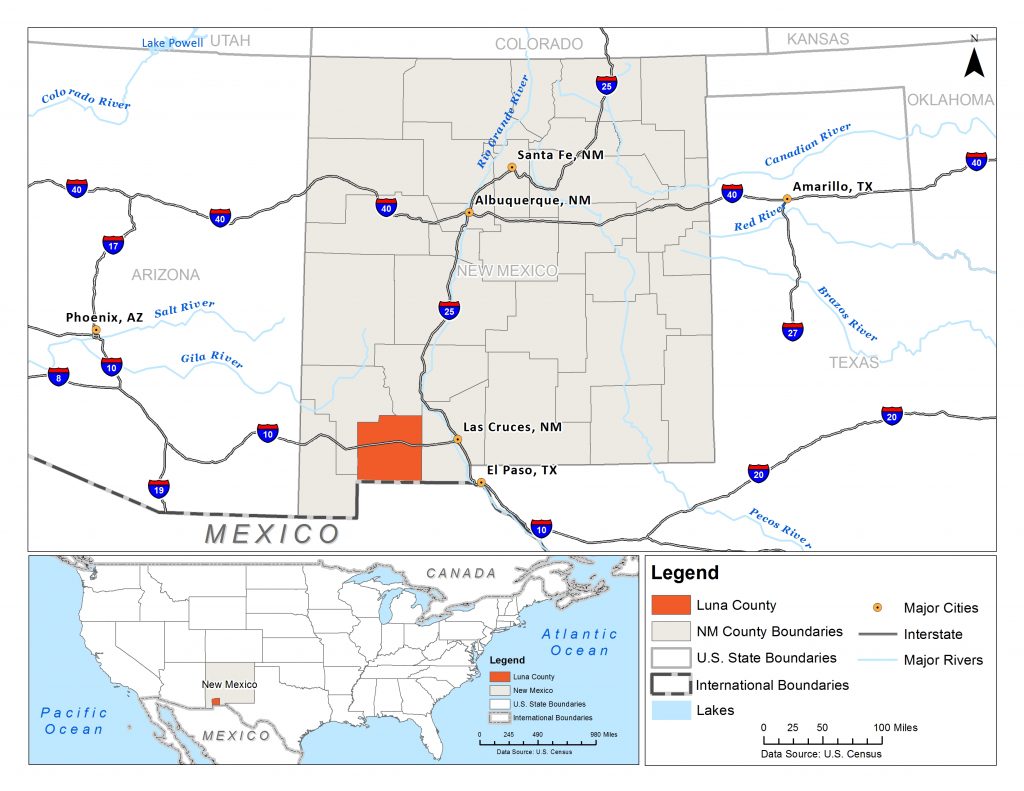

Bestowed with picturesque, arid landscapes, Luna County, New Mexico is home to a vibrant chile-pepper production and processing industry. Home to 24,947 people,3 Luna County is a rural place where community matters and water is the real gold. Located in southwest New Mexico (see Figure 1), Luna County spans approximately 3,000 square miles across the desert, encompassing mountain ranges, wilderness areas, and farmland.4 The federal and state governments manage most of the land area in the county (69%).4 The remaining 31% of the land area, or 919 square miles, is privately owned.4

The county is bordered by Sierra and Grant counties to the north, Grant and Hidalgo counties to the west, and to its east lies Doña Ana County, which is also a designated Growing Food Connections (GFC) Community of Opportunity. Luna County is an international point of entry between Chihuahua, Mexico and the United States and shares 54 miles of its southern border with Mexico.4

Enabled by the legal framework of “home rule” in the state of New Mexico, governance in Luna County occurs through three general-purpose governments: one county government and two municipal governments.5 Luna County also has three special-purpose governments: one independent school district and two special districts.5 The county has low population density: most (59%) of its 24,947 people live in the City of Deming, the county seat, and 6% live in the Village of Columbus. The remainder of the population makes its home across vast swaths of unincorporated lands and eight colonias.6

Luna County is fairly diverse and has a rich Hispanic tradition. U.S. Census Bureau data indicate that 63% of people (15,806) in the county self-identify as Hispanic or Latino, and 16% are foreign-born.3 The data also show that in terms of race, 90% of the population is reported to be white,3 and 10% comprise African Americans, American Indians, Asians, and other groups.3 Thus, the county’s single school district serves a diverse population of students. According to community stakeholders, the school district also serves children from the Mexican town of Palomas, who are bussed in daily from across the U.S.-Mexico border.7 The district has limited resources to provide services to students with limited English skills.8, 9 The district’s challenges and low ranking in comparison to other school districts in the state discourage families with children from relocating to Luna County.8, 9

Like many rural communities in the U.S., Luna has experienced economic hardship.10 The median household income is $28,489,3 and the county has the eighth-highest household poverty rate (30.6%) among the 447 counties of the western census region.11 The county has a high unemployment rate of 10.7%, which fluctuates with the agricultural production cycle.12 Scarce economic resources are associated with high rates of food insecurity for some households.7

Given these challenges, economic development is a priority for the community.7-9 One strategy to promote economic growth in the county has been to keep property tax rates low, which are among the lowest in the state.9 Community stakeholders acknowledge that it is difficult to facilitate economic development without changing the county’s rural character.9 Although vestiges of hardship persist, community members are working to implement additional strategies to improve the quality of life, such as exploring the potential for food systems to spur economic development. Community leaders note that Luna is an “incredibly giving community. [When] somebody stumbles and falls… [or] a little tragedy [happens]…, it’s amazing to see how the community pulls together.”13 Indeed, the community is pulling together to promote food security and agricultural viability in the county.

Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities

Luna County is located in Southwest New Mexico and abuts the Mexico border. Image Source: Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab

Luna County’s rich agrarian traditions have stood the test of time. Even today, agriculture is a key element of the economy. In 2012, the county’s 190 farms generated $62.5 million in agricultural product sales, $13.5 million more than in 2007.8, 14 According to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) census, about 69% of farms are “low sales intermediate” farms with gross sales of less than $100,000, 11% are “high sales intermediate” farms, and the remaining 20% are commercial family farms with gross sales of more than $250,000.14 Farms in the county are predominantly operated by white men, and farmers in the county are, on average, 58 years old.14

The top agricultural products sold include chile peppers, onions, pecans, and commodity crops such as hay and grains. Chile producers have the opportunity to supply a vibrant chile-processing industry in the county and region. The raising of livestock and ranches is quite common in Luna County. Many ranches are cow-calf operations: community stakeholders report that calves raised in Luna are sent to Texas, Colorado, or Oklahoma for fattening and then to the finishing yard.15 Dairy operations supply milk for cheese production to two plants in New Mexico, one in the nearby city of Las Cruces and another in the city of Clovis.15

Agriculture depends on the availability and quality of land and water in the county’s arid climate. About one-third (29%), or 550,174 acres, of land in the county is used for agriculture. Of the land used for agriculture, only a small proportion is cultivated as cropland: 6.8%, or 37,210 acres.14 Farms vary in size, ranging from a few acres (one to nine acres) to very large farms encompassing over 1,000 acres.14 Approximately half of the farms (52%) in the county use irrigation.14 The county also reflects a growing interest in urban agriculture. In the Village of Columbus, a public-civic collaborative partnership established a community garden with 12 raised beds of four-by-eight feet each.7 The Village of Columbus provided the land and installed water lines to each raised bed; New Mexico’s Economic Development Department provided initial grant funding to build the raised beds;16 a local nonprofit, Friends of the Columbus Community Garden (FOCCG), runs the daily programming.16 Programs teach participants gardening techniques, including starting seeds, weeding, composting, and rainwater harvesting.7, 16 The partnership hopes to increase interest in gardening and access to healthy foods.

Challenges

Although agriculture is doing well in the county, not all farmers are reaping the bounty equally. Most farms have low sales. Community stakeholders highlight several issues that undermine agricultural viability, including natural resource constraints, lack of adequate infrastructure, limited access to markets, labor constraints, and burdensome zoning rules.8, 9, 15, 17-19

Water in Luna County, as in much of the Southwest, is more valuable than gold. The only naturally occurring water source in the county is the Mimbres Basin, a closed water basin whose recharge depends on rainfall20 and snowmelt.4 Residents obtain water for municipal (domestic) and industrial uses through groundwater pumping made available by municipal utilities.4 Municipal utilities operate well fields within the municipalities, 12 in Deming and three in Columbus.4 Projections suggest that well fields will have difficulty meeting demand for water between 2040 and 2060.4 Agricultural producers have individual wells that supply their operations. The combined effects of increased salinity due to mining of the aquifers and the effect of climate change on snowpack formation and spring runoff are likely to sap water resources in the county.4 Therefore, purposeful management of the limited water supply for multiple users is paramount to the viability of agriculture.

To overcome constraints on water resources, farmers and municipalities have developed coping strategies. Farmers are switching from flood to drip irrigation to practice higher efficiency and conservation of water.8 The shift to subsurface drip irrigation also lowers the cost of pumping groundwater.9 However, not all farmers are switching; operators of larger farms can more easily afford the new drip-irrigation technology, compared to smaller farms.9 Federal funding from the USDA is available to farmers to defray the cost of new technology. To be eligible, farmers must have irrigated their land for at least two of the last five years.21 However, when federal funding became available, operators of many small farms had coped with the drought by allowing their land to remain fallow for more than three years.9, 21 The fallowing of land for more than two of the five years makes smaller farm operators ineligible to apply.9, 21 Lack of access to affordable water remains a challenge for urban growers, too. One community stakeholder reported that participants in the FOCCG community garden find it difficult to pay for municipal water to grow their crops.7 To overcome this challenge, FOCCG teaches and promotes rainwater harvesting.

Municipalities have coped with the dwindling access to water by buying water rights from farmers. New Mexico’s water laws give priority to users based on the date on which they acquired their water rights, as stipulated in the law of prior appropriation.22 Agricultural users were first in the county to obtain rights to use the water and are, therefore, senior water-right holders. All other users have a later priority date and have water rights that are junior to agricultural water rights. Municipalities have few options for sourcing potable water for current and anticipated future residents. The City of Deming has coped by purchasing land and its attached water rights from farmers, putting farmland out of production. During interviews, stakeholders implied that the City of Deming may be purchasing farmland for surplus water rights, to allow future population growth and development.19 Driven in part by this pressure, Luna County lost 8% of its farms, or over 103,000 acres of farmland between 2007 and 2012.14

A lack of local aggregation facilities also makes it difficult for farmers to bring their product to market. One critical piece of missing infrastructure is the lack of food processors for key crops such as pecans, onions, and jalapenos. The lack of local aggregators and wholesalers makes it more economical for farmers to send their agricultural products to a distributor in Texas rather than to supply the local market in Luna County.8 Similarly, retailers find it more convenient to purchase produce from a wholesaler than directly from local farmers, as one local interviewee explained: “Buying from local farmers is more work; and, farmers cannot guarantee safety of produce, while aggregators and wholesalers do.”13 Additional local infrastructural constraints include the absence of a slaughterhouse, commercial kitchen, and cold storage facilities.15, 17 The lack of wholesale and aggregation facilities in the county is a missed opportunity for creating direct connections between farmers and retailers.

Finally, the lack of an adequately trained workforce poses challenges to long-term agricultural viability. Farmers are aging, as in the rest of the country. Many interviewees perceive that local residents do not want to work on farms.8, 15 The labor shortage is affecting both conventional agriculture and urban agriculture efforts.8, 15 The county operates a community garden but has been unable to entice community members to work in the garden.8 The county leadership is exploring the possibility of having youth from the juvenile detention facility work in the community garden. Community stakeholders view the development of an effective solution to the labor shortage as critical to sustain agriculture.

Opportunities

Luna can draw on its strong heritage in farming and ranching to enhance agricultural viability. While its changing climate presents new challenges, it also provides a long growing season and favorable conditions for specialty crops. As mentioned above, local government agencies and non-governmental organizations are exploring solutions to some of the challenges that confront farmers in Luna, especially around access to water. A key challenge is that many existing policies and programs benefit operators of larger farms rather than small farms. A commitment to reducing barriers for small farmers, as well as urban farmers, offers opportunities to strengthen agricultural viability in Luna through local government policy. Beyond programs and policies, there is also a need for and opportunities to invest in physical infrastructure development such as food processing and storage facilities.

Food Security: Challenges and Opportunities

Hunger and limited access to healthy foods remain a concern in Luna County. Recent data suggest that 5,390 people, or 21.6% of the population, are food insecure in the county.23 According to interviewees, a large proportion of food-insecure people are undocumented workers who have difficulty securing employment.9 Additionally, at least 26% of households in the county rely on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to meet their food needs.3 Luna County also has the second-highest rate of child hunger in New Mexico, which is a concern given that New Mexico ranks worst for child hunger nationally.23 Food insecurity is associated with deep levels of poverty in Luna County.8, 19 One interviewee noted, “to have the healthy food, you actually need to have more of a disposable income…”8

Challenges

Along with hunger, poor health outcomes are also a concern in Luna County. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that in Luna County, 10.6% of adults over 18 are diagnosed with diabetes and 24.3% are considered to be obese.24 Interviews in the community affirm concerns about diabetes.7 Data also suggest that only a small proportion of adults (18%) and youth (18.5%) in Luna County consume the recommended amount of fruits and vegetables.25 Poor diet, food insecurity, and poor health outcomes reflect the county’s socioeconomic challenges.

Spatial disparities in food access also persist in the county. As in many rural communities, the availability of food retail operations is limited: 0.16 grocery stores, 0.04 supercenters, and 0.68 convenience stores are available for every 1,000 people in the county.26 Most food retail operations are located in Deming. For those who live elsewhere in the county, limited access to full-service food retail severely affects access to affordable fresh produce.7, 17 People without access to cars are the most affected by these spatial disparities.19 Moreover, little home/backyard gardening occurs to supplement produce needs.7

Opportunities

Fortunately, several local initiatives provide relief from the food deficit faced by the 21.6% of households in Luna County that receive assistance from SNAP. One initiative provides free breakfast and lunch to children in the school district.17 The Deming School District also runs a backpack program that provides food for children to take home over the weekends.17 Community stakeholders report that for some children, “…the only meals that they [get] are at the school. And that’s why [the program provides] free meals at … school for breakfast and lunch.”17 Additionally, the Helping Hand food pantry, with support from other organizations, provides a safety net for households in the county. A local grocery store (Peppers) provides a discount of up to $1,500 for food products and produce to the regional food bank, Road Runner, which delivers food to Helping Hand once each month.13 Helping Hand then makes this food available to hungry people. Although these initiatives alleviate hunger, systemic changes are needed to ensure long-term food security.

Local Government Public-Policy Environment

A strong policy environment can positively transform a food system by simultaneously improving agricultural viability and reducing food insecurity. In Luna County, the government has played a leadership role to improve conditions, as detailed below.

Planning for Agriculture

The county’s comprehensive plan supports preservation of agricultural land uses as a strategy for maintaining its agrarian identity and addressing food insecurity.4 The plan notes, “retaining local agriculture rises to a level of protecting public health, safety and welfare.”4 Among its numerous goals and associated strategies, the plan advocates the adoption of a “Right-to-Farm Ordinance,” development of critical management areas (that include agriculture), and encouragement and incentives for compact development patterns (cluster development) near municipalities, to minimize sprawl and maximize efficient use of existing infrastructure.4 Luna County’s comprehensive plan is an important tool that can support both local farmers and food-insecure residents.

Joint Powers Agreements

Joint powers agreements are a means of sharing administrative power and costs for initiatives among local governments and other public agencies in the state.8, 27 This regional power and cost sharing is made possible through the state’s Joint Powers Agreements Act. The New Mexico legislature introduced the Joint Powers Agreements Act in 1978, which allows “public agencies” to enter into contractual agreements with other public agencies and public corporations, to share resources and support local economic and infrastructure development, among other things.28 In addition to allowing public agencies to collaborate, the act enables public agencies to issue revenue bonds to cover the costs of pursuing the agreements.28

In at least one instance, a joint powers agreement has been used to support food initiatives in the county. For example, a joint powers agreement with the Village of Columbus and FOCCG facilitates support for community gardens in the village.7 The agreement allows the Village to provide land, utilities, and liability insurance for the project, while FOCCG runs the programming: education, daily management, instruction, and fundraising.7, 16 The agreement allows a cooperative structure between the Village and FOCCG, which the state recognizes. This local government tool has become central to how the county supports local food initiatives.7 The joint powers agreement is a broad, flexible tool that could be applied to support other food system initiatives in the county.

Economic Development Tools for Food Systems Transformation

Another innovative tool that municipalities can use is the Local Economic Development Act (LEDA). LEDA, introduced in 1993 by the New Mexico legislature, provides a framework for local governments to use public dollars to spur economic development.29 The public dollars for LEDA are allocated in the state budget each year, and funding varies from year to year.30 LEDA allows the formation of public-private partnerships, to promote economic development projects.29 In 2013, the state amended LEDA to extend funding to retail businesses in rural areas, and subsequently, in 2014, Luna County adopted a local economic development plan ordinance that facilitates use of LEDA funding.29 Luna County has since provided both technical and financial assistance to small businesses, including those in the food sector, to access LEDA funds. For example, in 2015, Luna County provided multipronged economic development assistance to Preferred Produce, a local greenhouse producer. The county assisted Preferred Produce with its LEDA funding application to the state, access to funding, and improving road infrastructure in the vicinity of the business.8 In addition, Luna County in 2015 passed a local ordinance to recommend that Preferred Produce be awarded $135,000 in LEDA funds to expand their current facilities by 45,000 square feet.8, 31 In early 2015, the New Mexico Economic Development Department approved the expansion, which is expected to generate at least ten high-paying jobs, with a starting salary of $30,000, by 2018.8, 31 Facilitating this transformation would not be possible without the support of Luna County staff.

Financial, Technical, and Staffing Support for Food Projects

The Luna County government provides extensive financial, technical, and human-resource support to county food initiatives. Financial support for food initiatives are funded directly either through the county budget or LEDA funds. For example, the county provides the senior center $100,000 annually, part of which is dedicated to providing meals to seniors (seniors can donate toward the cost of meals).8 The planning office also provides technical and human-resource support to aid small food businesses. County planning staff provides support (similar to that provided to Preferred Produce) to other small businesses, including farmers and restaurants, by procuring loans and funding either through LEDA or by guaranteeing loans through the USDA or the New Mexico Finance Administration.8 County planning staff also provides training regarding grant applications, for small businesses. Most recently, Mizkan, a chile processor in the county, received training for their staff.8 In addition, county staff also prepared and submitted an application for the USDA’s Rural Business Development Grant to provide a permanent cover for the farmers’ market.8

Ideas for the Future

Commitment to agriculture and food security is evident in the efforts of the county government and community groups in Luna County. Greater support by local governments can amplify these initiatives to support food and agriculture. Community stakeholders identified multiple levers of change to improve agricultural viability and reduce food insecurity. Community stakeholders recommended simultaneously increasing local production of fruits and vegetables and expanding the farmers’ market, to alleviate spatial disparities in food access.8 Interviewees recommended increasing nutritional education and awareness programming in the community.8, 9, 19 Interviewees expressed concerns that even though some schools operate gardening programs, current regulations prohibit school staff from using (cooking) garden produce as part of the school meals on site.8 Changing regulations so that they support local healthy food initiatives could positively shift the food landscape in Luna County. Below are several suggestions to help move food policy forward systematically and strategically in Luna County.

Reduce the Regulatory Burden on Agricultural Activities

The City of Deming can carefully modify plans and ordinances to allow more agricultural activities. Currently, community gardens and urban agriculture are not explicitly permitted land uses in the city, and neither is the raising of livestock in the residential, commercial, and industrial zones.32 In addition, landscaping ordinances severely limit residents’ ability to (legally) maintain backyard gardens.32 Currently, very little land is agriculturally zoned within the city, further limiting access to land for subsistence and community agriculture. Zoning ordinances can be modified to permit agricultural activities in the city. For example, landscaping ordinances can be modified to allow backyard gardens that help recharge the aquifer through xeriscaping. Xeriscaping minimizes water use by prioritizing plants with low water usage (edible varieties include prickly pear and rosemary) and by allowing small plots of plants such as fruit trees and vegetable gardens.33, 34 Similarly, allowing certain livestock, such as chickens, within the city limits can be advantageous for addressing food security in the county. A number of local governments from across the country have taken a whole host of actions to support urban (and other forms of) community food production including by creating and implementing agricultural plans (Marquette County, Michigan); adopting supportive land use and zoning regulations (Minneapolis, Minnesota); using public lands for food production (Lawrence, Kansas); and supporting new farmer training and development (Cabarrus County, North Carolina).35 The city and county governments of Deming and Luna can leverage their communities’ assets and knowledge to create a supportive policy environment for community food producers.

Develop a Food System Plan

Another way to strengthen the food-policy environment is to implement the agrarian goals in the county’s comprehensive plan through the development of a county food system plan. The development of a food system plan would include a countywide assessment of assets, needs, strengths, and opportunities guided by a set of visions and goals to help the county identify short-, medium-, and long-term policy actions to support the local food system. Similarly, the City of Deming might consider strengthening food system considerations in its policies by either jointly working with the county on the food system plan or by conducting a citywide food assessment. An informed food system plan will provide a tangible framework that both supports agrarian viability and improves food security for the county and city. Examples of food system plans are available through the Growing Food Connections Local Government Policy Database.36

Invest in Food Infrastructure Development

A key agricultural challenge mentioned by community stakeholders was the absence of food infrastructure. In particular, stakeholders indicated that having a local pecan processor would benefit the area’s farmers. Additionally, the lack of cold storage and commercial kitchen facilities have hindered the agricultural economy. Such facilities would, first, allow farmers to extend the shelf life of produce, and second, develop value-added products from unsold produce.15 Another critical element of food infrastructure that community stakeholders highlighted is the need for aggregation facilities in closer proximity to farmers and retailers. The development of such a facility in Luna County would make it easier for farmers to serve the local community. The introduction of local aggregation would also help retailers purchase more locally grown produce. Given Luna County’s history of using local government tools to attract processors to the area, the county can use tools such as LEDA to add much-needed processing plants and other critical food infrastructure. The policy brief Food Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution, which draws on innovative experiences from across the country, outlines the many ways in which such infrastructure for fresh fruits and vegetables has been supported by local government.37

Establish a Good Food Purchasing Program

A good food purchasing program can create additional connections between farmers and consumers. A good food purchasing program creates pathways to encourage public institutions to purchase local food, which creates an equitable food system. Through a joint powers agreement between public institutions in Luna, both the city and county can support local (small- and medium-sized) farmers by purchasing directly from farmers and by encouraging more farmers to produce fruits and vegetables for the local market. City and county procurement policies can be amended to include preferential language on sourcing a certain percentage of agricultural products from the local markets. Given the obstacles that farmers face in working with public institutions, payment methods and requirements may need to be amended to increase the feasibility of institutional purchasing agreements. The policy brief Incentivizing the Sale of Healthy and Local Food details the experience of urban communities such as Baltimore, Maryland, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Washington D.C. as well as rural Marquette County, Michigan that may be helpful as Luna takes next steps.38

Use Regionalism to Strengthen Food Systems

Luna County’s proximity to communities with similar agrarian conditions and challenges creates an opportunity to use regional food system approaches to strengthen rural economies. Tools such as the Joint Powers Agreements Act and LEDA can help to establish regional connections in the food system. Examples of regional approaches have been tried in rural communities elsewhere.36 Consider the case of Region 5, Minnesota, which includes Cass, Crow Wing, Morrison, Todd, and Wadena counties in rural Minnesota. Region 5 has implemented multiple actions to generate local wealth and provide access to healthy, affordable foods.39 One action has been the creation of the Sprout Growers and Makers Marketplace.39 The marketplace is a regional food distribution and processing facility serving and connecting farmers and institutions.39 As an aggregation and distribution facility, the marketplace aggregates thousands of pounds of commodities from community supported agriculture operations across the five-county region. Luna County’s proximity to other counties allows it to undertake a regional approach. Luna County can play a leadership role in establishing a regional framework, given its history of strengthening food systems by using LEDA and joint powers agreements.

Research Methods and Data Sources

Information in this brief is drawn from multiple sources. Quantitative data sources include the 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates and the 2012 U.S. Census of Agriculture. Qualitative data include eight in-depth interviews with representatives of various sectors of the food system as well as Luna County, City of Deming, and Village of Columbus policymakers and staff. Interviewees are not identified by name but are, instead, shown by the sector that they represent, and are interchangeably labeled as interviewees or stakeholders in the brief. Interviews were conducted from April to August 2015. Qualitative analysis also included the policy and planning documents of the local and regional governments, which were reviewed for key policies and laws pertaining to the food system, and a review of the minutes of the Growing Food Connections steering-committee meetings.

Acknowledgments

The GFC team is grateful to the Luna County GFC steering committee, Luna County government officials and staff, and interview respondents for generously giving their time and energy to this project.

Notes

1 Growing Food Connections, “Eight ‘Communities of Opportunity’ Will Strengthen Links Between Farmers and Consumers: Growing Food Connections Announces Communities from New Mexico to Maine,” http://growingfoodconnections.org/news-item/eight-communities-of-opportunity-will-strengthen-links-between-farmers-and-consumers-growing-food-connections-announces-communities-from-new-mexico-to-maine/.

2 C. Marquis and J. Freedgood, “Luna County, New Mexico: Community Profile,” Growing Food Connections Project (Buffalo, NY: University at Buffalo, 2016).

3 U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, 2010-2014 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

4 Luna County, Comprehensive Plan Update (Luna County, NM: Luna County, 2012).

5 U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 Census of Governments: Organization Component Estimates (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012).

6 Colonias are communities in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas, within 150 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border. Luna is home to several federally recognized colonias in New Mexico. Colonia is a federal definition used to identify communities that can be targeted for federal aid for infrastructure development. Colonias are characterized by lack of adequate water, sewage, gas systems, and decent, safe, and sanitary housing.

7 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Luna County (ID 67), June 3, 2015.

8 Interview with Local Government Representative in Luna County (ID 68), June 1, 2015.

9 Interview with Local Government Representative in Luna County (ID 72), April 13, 2015.

10 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rural America at a Glance: 2016 edition (Washington, D.C.: Economic Research Service, 2016).

11 U.S. Census Bureau, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates Program (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

12 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate – Not Seasonally Adjusted (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, 2015).

13 Interview with Food Retail Representative in Luna County (ID 74), June 1, 2015.

14 U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012 Census of Agriculture (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

15 Interview with Cooperative Extension Representative in Luna County (ID 103), September 22, 2015.

16 K. Naber, “Garden Grows in Village,” Deming Headlight 2016.

17 Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Luna County (ID 69), June 1, 2015.

18 Interview with Farming and Agriculture Representative in Luna County (ID 73), June 1, 2015.

19 Interview with Local Government Representative in Luna County (ID 70), June 2, 2015.

20 On average, Luna County receives 10 inches of rainfall annually.

21 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Environmental Quality Incentives Program, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/nm/programs/financial/eqip/.

22 New Mexico Statutes Annotated. §72-14-3.2; 2003.

23 C. Gundersen, A. Dewey, A. Crumbaugh, M. Kato, and E. Engelhard, Map the Meal Gap 2016: Overall Food Insecurity in New Mexico by County in 2014 (Chicago, IL: Feeding America, 2016).

24 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, County Data (Washington, D.C.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

25 New Mexico Department of Health Public Health Division, New Mexico’s Indicator-Based Information System (NM-IBIS) 2016, https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/community/highlight/profile/NurtiAdultFruitVeg.Cnty/GeoCnty/29.html.

26 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Environment Atlas (Washington, D.C.: Economic Research Service, 2015).

27 White, Samaniego, and Campbell LLP, State of New Mexico, Village of Columbus: Basic Financial Statements and Supplementary Information for the Year Ended June 30, 2014 and Independent Auditors’ Report (Columbus, NM: Columbus Village Council, 2014).

28 New Mexico Statutes Annotated 1978, Joint Powers Agreements Act Vol Chapter 11 (Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Legislature, 2016).

29 New Mexico Statutes Annotated 1978, Local Economic Development Act (Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Legislature, 1993).

30 Representative L. “Lucky” Varela and Senator J.A. Smith, Report of the Legislative Finance Committee to the Fifty-Second Legislature First Session, Volume 1 Legislating for Results: Policy and Performance Analysis, January 2015 for Fiscal Year 2016 (Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Legislature, 2015).

31 A. Heisel, “New Mexico Economic Development Department and Luna County to Announce Preferred Produce Expanding, Nearly Doubling Workforce,” (Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Economic Development Department, 2015).

32 City of Deming, Zoning Regulations 12 (Deming, NM: Deming City Council, 2001).

33 C. Vogel, “Teaching Water Awareness Through Xeriscaping,” Green Teacher: Education for Planet Earth (2003): 23–29.

34 Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority, Xeriscaping: The Complete How-To Guide (Albuquerque, NM: Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority, 2010).

35 A. Dillemuth, “Community Food Production: The Role of Local Governments in Increasing Community Food Production for Local Markets,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2017), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCFoodProductionPlanningPolicyBrief_2017August29.pdf.

36 S. Raja, J. Clark, J. Freedgood, and K. Hodgson, Growing Food Connections: Local Government Food Policy Database (Buffalo, NY: University at Buffalo, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/tools-resources/policy-database/.

37 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Food Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCFoodInfrastructurePlanningPolicyBrief_2016Sep22-3.pdf.

38 A. Dillemuth and K. Hodgson, “Incentivizing the Sale of Healthy and Local Food,” (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/GFCHealthyFoodIncentivesPlanningPolicyBrief_2016Feb-1.pdf.

39 K. Hodgson and K. Martin, “Building from the Inside Out in Region 5, Minnesota: A Rural Region’s Effort to Build a Resilient Food System,” in Exploring Stories of Innovation, edited by K. Hodgson and S. Raja, 4 (Buffalo, NY: Growing Food Connections Project, 2016), http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/08/GFCStoryOfInnovation_Region5Minnesota_2016Sep22.pdf.

Community of Opportunity Feature

AUTHORS

Subhashni Raj, University at Buffalo

Joseph E. Quinn, University at Buffalo

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

CONTRIBUTORS

Jill Clark, Ohio State University

Julia Freedgood, American Farmland Trust

Kimberley Hodgson, Cultivating Healthy Places

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

SERIES EDITOR

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

PROJECT COORDINATOR

Enjoli Hall, University at Buffalo

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Brenda Stynes, University at Buffalo

Daniela Leon, University at Buffalo

Samantha Bulkilvish, University at Buffalo

Clancy Grace O’Connor, University at Buffalo

Recommended citation: Raj, Subhashni, Joseph E. Quinn, and Samina Raja. “Supporting the Chile Capital of the Southwest: The Role of Local Government in Sustaining Farming Traditions in Luna County, New Mexico.” In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited by Samina Raja, 13 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project, 2018.