Print Version (PDF).

Cultivating a Culture of Health: Growing a Local Food Economy for a Healthy Wyandotte

In March 2015, Wyandotte County, Kansas was selected as one of eight Communities of Opportunities (COOs) in the country that have significant potential to strengthen ties between small- and medium-sized farmers and residents with limited food access.[i] Working with the Growing Food Connections (GFC) project team, county stakeholders have since established a steering committee that has charted a vision for the future of Wyandotte’s food system.[ii] This brief, which draws on interviews with Wyandotte County stakeholders and secondary data sources, provides information about local government policy opportunities and challenges in the food system to inform the work of the GFC steering committee and stakeholders in Wyandotte County.

Background

A transformation is quietly underway in Wyandotte County and its major city, Kansas City, Kansas (KCK). Community stakeholders and local government agencies are working together to make the county a healthier place for all residents. Local government agencies are beginning to recognize the central role of the county’s food system in creating a healthier county, fueled in part by calls from community coalitions and by concerns over public-health disparities.

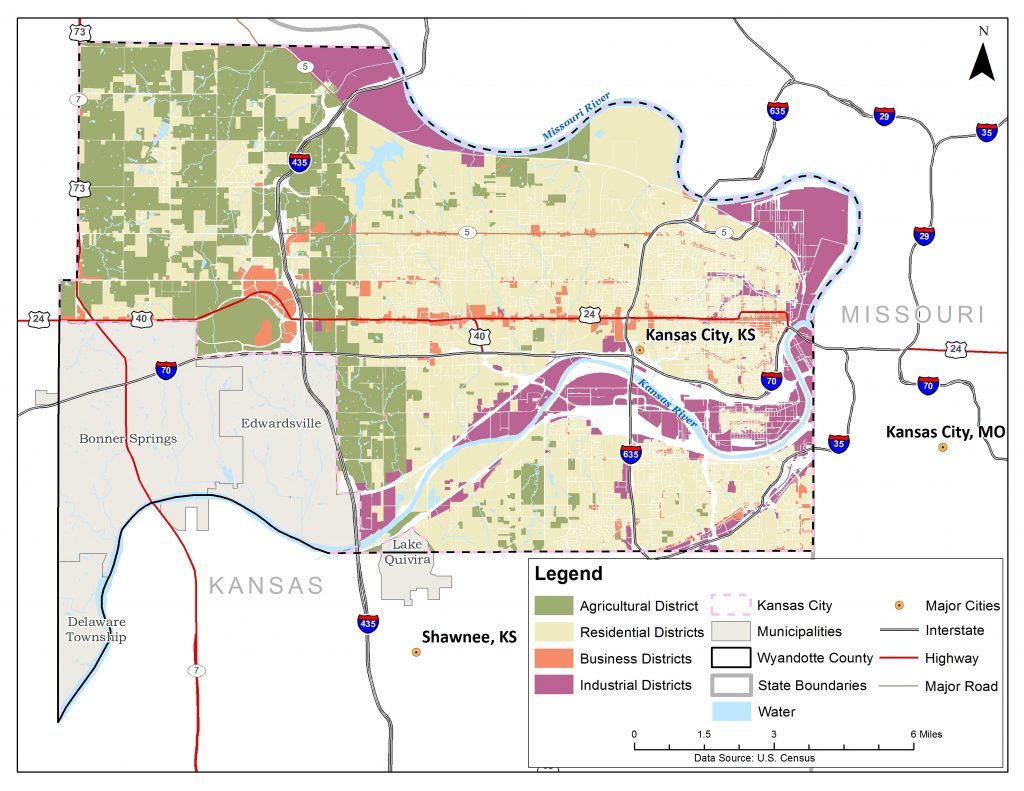

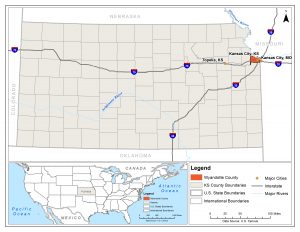

Wyandotte County includes the city of Kansas City, Kansas as its major municipality and three other small communities.[iii] The county seat is in Kansas City, and a unified county-city government (UG), formed in 1997 following a local government vote, serves both the city and county. Wyandotte County (and KCK) is located within the vibrant Kansas City metropolitan region, a 14-county area that straddles the states of Kansas and Missouri (the Kansas City metropolitan area includes Kansas City, MO and Kansas City, KS, locally called KCMO and KCK, respectively. See Figure 1). The smallest county by land area (151.60 sq. miles)[iv] but fourth largest by population, Wyandotte County is bordered by the Missouri River on the northeast and the Kansas River to the south. Reports of settlement in the county date back to the 1500s, with the arrival of several first nations, including the Kansa tribe, which hunted its hills and valleys in the 16th century, the Shawnee and Delawares, who emigrated there in the 1800s, and the Wyandots, who made the region their home in 1843 and gave the county its name. The county’s population grew steadily until the early 1970s, when the county experienced population loss, in part due to suburbanization and white flight from Kansas City. In recent years, however, the population decline has stemmed, and the economy is beginning to see signs of resurgence.

Today, Wyandotte County is home to a diverse population. The county’s 159,466 residents, most of whom live within Kansas City (KS), come from various backgrounds. Nearly 30% (26.8%) of the population, or 42,801 residents, identify as having Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. The county is also racially diverse: about 60% of the population is white, a quarter of the population is African American, 3% is Asian, and another 6% identify as belonging to another race. People who have settled in Wyandotte County come from various countries. Indeed, today the county is home to 52 different immigrant communities, including groups of recently resettled refugees.[v] About 15% of the county’s population is foreign born. Community stakeholders interviewed for this brief report that many refugees are Hmong people from Laos and Chin people from Myanmar.[vi]

Along with a growing, diverse residential population, Wyandotte County is experiencing burgeoning commercial development along its western corridor. Interviewees attribute this growth to the issuance of the Sales Tax Revenue (STAR) bonds for the development of the Kansas Speedway in 2001, the first county to do so in Kansas. STAR bonds allow a municipality to finance the development of major commercial development and use the sales tax revenue to pay off the bonds. Despite this resurgence, however, poverty and economic hardship persist. About one-quarter (24.3%) of the county’s residents live below the federal poverty line, and the average median household income is $39,326, lower than the state average of $51,872.[vii] Community stakeholders report that only a small proportion of county residents are employed in high-paying jobs, resulting in a low average income in the county.[viii] In May 2015, the unemployment rate in the county was 6.1%, compared to 4.4% statewide.[ix] Not surprisingly, local government officials have identified workforce development and economic development as top public-policy priorities.[x]

Despite the economic challenges, the county is poised for change. Much of this change is occurring because of innovative partnerships among organizations from the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors. These partnerships, and the potential for change, are especially evident in the area of agriculture and food systems.[xi]

Agriculture: Conditions, Opportunities, and Challenges

Wyandotte County has a rich history of agriculture. For example, reports suggest that, as early as 1910, Wyandotte County produced more corn than states with rich agricultural traditions, such as Wyoming or Idaho, produced. Agricultural bounty in Wyandotte was diverse, including wheat, oats, fruits, vegetables, and dairy.[xii] Nonetheless, by mid-century the processes of suburbanization contributed to the conversion of agricultural lands to other uses.[xiii]

Wyandotte County has a rich history of agriculture. For example, reports suggest that, as early as 1910, Wyandotte County produced more corn than states with rich agricultural traditions, such as Wyoming or Idaho, produced. Agricultural bounty in Wyandotte was diverse, including wheat, oats, fruits, vegetables, and dairy.[xii] Nonetheless, by mid-century the processes of suburbanization contributed to the conversion of agricultural lands to other uses.[xiii]

The network of urban farms and community gardens, which exist on both public and private land, is supported by several community organizations, including Cultivate Kansas City and Kansas City Community Gardens (KCCG).[xviii] Cultivate Kansas City operates two urban farms, one on land leased annually from the Kansas City Housing Authority and another on private land. The organization offers agricultural trainings and apprenticeship programs. One farm, located on Gibbs Road, produces 25,000 pounds of organic produce––with over 40 types of crops––resulting in annual sales of about $100,000.[xix] Cultivate Kansas City sells produce directly to consumers via farmers’ markets and through a 40–member community supported agriculture (CSA) operation.[xx] The second farm, Juniper Gardens, sits on eight acres of previously vacant public land adjacent to Juniper Gardens public housing, and houses a farm-business development program that offers training to new farmers, including long-term residents and refugees.[xxi] The New Roots for Refugees program, operated in partnership with Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas, focuses primarily on helping resettled refugee women start their own small farm business and settle in the community.[xxii]In addition to conventional farming of commodity crops, a new kind of farming is emerging in Wyandotte County. Small-scale urban agriculture, ranging from commercial urban farms to community gardens, has emerged within city boundaries in recent years. Local officials describe urban agriculture as a “burgeoning micro industry.” The potential for expanding urban agriculture in the county is significant. The UG owns about 6,000 vacant lots,[xvi] many of which could be used for expansion of urban agriculture in the county. Food-systems stakeholders report that small-scale urban agriculture in Wyandotte County contributes to alleviating food insecurity in the county and provides a social safety net for the county’s immigrant and refugee populations.[xvii] Systematic conversion of publicly held vacant land to urban agriculture would also reduce the public cost of maintaining vacant lots.

KCCG supports urban agriculture efforts in the larger Kansas City metropolitan region, including Kansas City, KS and Kansas City, MO. KCCG supports 250 community partner gardens. These include gardens operated by institutions or organizations, such as homeless shelters; 200 school gardens; eight community gardens, where residents can rent plots; and over 1,000 home gardens. KCCG provides technical assistance, garden resources at low prices, and tilling services to low-income members.[xxiii]

A network of community gardens and urban farms is supported by multiple community organizations.

Image Source: American Farmland Trust

Despite these opportunities, agriculture also faces serious challenges. Between 2007 and 2012, the number of farms declined by 14%, and the market value of agricultural products declined from $5.1 to $3.3 million.[xxiv] Farmland on the fringes of KCK is under constant development pressure. Growers report extreme weather swings as a challenge. Agriculture is also hindered by limited access to local markets, a barrier reported by conventional and urban agriculture farmers.[xxv] Community stakeholders note the absence of a wholesale aggregation facility, which impedes access to new markets such as large institutions: hospitals and school districts. A regional food-hub initiative, Fresh Farm HQ, launched in 2016 and aims to serve the greater Kansas City region.[xxvi] The opening of the food hub is an important first step to support Wyandotte County farmers.

Urban farmers face unique struggles as well. Residents find it difficult to access publicly owned vacant land. Additionally, creating contiguous land parcels for a viable urban farming operation is difficult, as land in the urban core has been subdivided and developed.[xxvii] One interviewee described accessing land for urban farming as a “politicized” process.[xxviii] Another interviewee reported opposition to urban agriculture in some neighborhoods: “There are some very loud voices that are quite opposed to urban agriculture … because urban agriculture is very visible … there is a lot of resistance to both urban agriculture and food-system change.”[xxix] Stakeholders also report high (and subjective) property-tax assessments as a barrier to urban agriculture.[xxx] Land is reported to be assessed at a residential rate even when it is used for agriculture. The higher tax assessments affect the farmers’ ability to purchase land for urban agriculture. One interviewee noted, “If you don’t have a roof on the lot you are not generating enough property taxes and Wyandotte County needs property taxes.”[xxxi]

Finally, urban farmers and gardeners also report access to water as a challenge. One interviewee reported that the one-time connection cost of a public water-supply connection, between $4,000 to $9,000 per connection, was prohibitively expensive for urban farmers, an issue that the local government has begun to address through its H2O Grow program, described further below.[xxxii]

Food Security: Conditions, Opportunities, and Challenges

Wyandotte County faces numerous food-security challenges. According to a 2014 study, 18.1% of the county’s population (28,940 people) was food insecure, making it the most food insecure county in the state.[xxxiii] Low income levels are reported as the key cause of the high degree of food insecurity.[xxxiv]

The county’s population also experiences diet-related challenges. About 46.6% of adults in Wyandotte County reported eating fruits less than once a day; similarly, 25.9% of adults reported eating vegetables less than once a day.[xxxv] Diabetes ranked among the top five causes of death in 2013, and 12.8% of Wyandotte’s residents have diabetes, while 38.3% of the adult population is considered obese.[xxxvi] A national health ranking placed Wyandotte County last in public-health metrics in the state of Kansas in 2009,[xxxvii] which triggered many of the public-private efforts described in this brief to improve public health in the county. Improving the county’s health rankings remains a significant local government priority,[xxxviii] as the county continues to be ranked last in the state in 2016.[xxxix]

Along with socioeconomic constraints, spatial disparities in access to food retail worsen food insecurity. Recent reports suggest that 31% of the population (48,750 people) has low access to healthy food retail.[xl] Interviewees pointed to the lack of food retail in certain neighborhoods. One interviewee pointed to the “concentric circles [that can] be drawn around different parts of our community without access to any kind of fresh fruit or grocery store.”[xli] Food-retail stores that stock healthy and culturally acceptable foods for the county’s ethnic population are especially limited. Availability of healthy food is further impeded by the lack of transit options and low vehicle ownership.[xlii] As one interviewee explained, “If you didn’t have a car and you had to take the bus it would be very difficult; you would have to do serious planning to make sure you get your grocery shopping done and get home…I think that is probably the biggest issue… How long does it take you to get to healthy foods, or do you just go down to Dollar General and buy whatever they have because it’s faster?”[xliii] Another interviewee remarked that some population groups also lack information on how to use public transit, and others are uncomfortable using transit services.[xliv] Having geographically proximate food-retail options could help alleviate food insecurity.

Local community stakeholders believe that all community residents deserve access to affordable, healthy, and culturally acceptable foods,[xlv] and are taking steps to achieve such community-wide food security. Food banks and pantries, including Harvesters and the Episcopal Church community services, run anti-hunger programs in Wyandotte County.[xlvi] Similarly, Cultivate Kansas City, the urban agriculture organization described above, operates Double Up Bucks Kansas City (previously called Beans and Greens), a program that incentivizes the purchase of produce at farmers’ markets by providing matching dollars to recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).[xlvii] A local grocery chain in partnership with Good Natured Family Farms, a group of 150 local and small family farms, supported a similar Double Up Bucks program for SNAP recipients within their grocery stores.[xlviii] Because of the success of these pilot efforts, the community has secured a significant grant to expand incentives for the purchase of healthy and local foods. The Double Up Heartland collaborative secured $5.8 million, which includes a $2.9 million grant from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive (FINI) program, matched equally by private foundations and local government.[xlix] The FINI grant enables the expansion of the pilot Double Up Bucks program, enabling SNAP recipients to buy healthy, fresh produce by doubling the value of their SNAP dollars at grocery stores and farmers’ markets throughout the KC metro area. In Wyandotte County, SNAP recipients can take advantage of this new incentive at all Price Chopper grocery stores, a mobile market, and farmers’ markets located in the county, starting June 2016.[l]

Local government support for urban agriculture has contributed to its rise in Wyandotte County. Image Source: American Farmland Trust

Wyandotte County stakeholders recognize that achieving community food security requires a comprehensive and nuanced approach. For example, one stakeholder noted, “You have to have a grocer that understands different ethnic groups’ needs… It is no good to provide fresh fruits and vegetables that are not customary to an ethnic group.”[li] Another noted the need to supplement efforts to increase healthy food retail with programs that educate residents about how to cook with fresh, healthy, and seasonally available foods.[lii]

Despite the magnitude of challenges, community stakeholders report that the tide is turning against food insecurity. They point to Wyandotte’s collaborative approach, which includes multiple coalitions, stakeholders, and organizations, as a cornerstone of their success in reducing food insecurity.

Local Government Public Policy Environment

Stronger public-policy support, especially from local governments, can amplify community efforts to promote agricultural viability and food security. Local governments are able to create plans, operate programs, and provide financial support to strengthen local food systems. As detailed below, the Unified Government of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas has launched several policy supports, with significant opportunity to improve the food system, local economy, and public health.[liii]

Consolidated Governance

Although not directly a food policy, the consolidation of the governments of Kansas City and Wyandotte County into a Unified Government[liv] is an unusual policy environment that has the potential to create a stronger food system by tying the urban core to more rural areas of the county. As authorized by the home-rule state of Kansas (chapter 12 of the State Statute and article II of the State constitution), the UG[lv] provides all local government functions, including planning and zoning, for the entire area of Wyandotte County.[lvi] The consolidation marks the region’s openness to policy innovation.[lvii] The consolidated form of government has the potential to allow the local government to foster food-systems-related activities in a more coordinated and efficient manner across its jurisdictions.

Healthy Communities Wyandotte

In 2010, the mayor of the UG commissioned a health task force to address the county’s poor public-health rankings. This led to the formation of Healthy Communities Wyandotte (HCW), a program housed within the Wyandotte County Health Department to coordinate and guide efforts to improve public health.[lviii] HCW is guided by a steering committee of community stakeholders and supported by a policy subcommittee and six action teams: communication, education, infrastructure, nutrition, health services, and tobacco-free Wyandotte. HCW facilitated the development of a community health-improvement plan, published in 2011, which squarely addresses the health of the Wyandotte County food system.[lix] In 2014, the mayor’s office also convened a food summit to strategize means for improving food security. Community stakeholders point to the establishment of HCW as among the most promising public efforts in the county. The county leaders, especially the mayor, recognize the local government’s power of convening stakeholders as critical to strengthening the local food system.

Ordinances to Support Urban Agriculture and Farmers’ Markets

UG ordinances support the raising of food and livestock in the county. For example, the zoning ordinance permits urban agriculture as a permitted use in residential zoning districts in the city and county. The zoning code allows livestock in agricultural districts and in some residential zoned districts. Specifically, small livestock, including chickens, are permitted within residential districts on one-acre lots by special-use permit.[lx]

The UG zoning ordinance was also amended in January 2016 to reduce regulatory barriers for the establishment of a farmers’ market.[lxi] The amendment defines farmers’ markets as “any common facility or area where fruits, vegetables, meats, other local farm or consumable products, etc., are sold directly to consumers by producers, growers, and sellers at more than one stand operated by different persons,” and “local produce” is defined as grown within 100 miles of the KCK limit. The Department of Urban Planning and Land Use now permits farmers’ markets as an accessory use in many zoning districts upon submission and approval of an annual agreement.[lxii] The amendment also permits farmers’ markets, with a special-use permit, in multiple zoning districts.[lxiii]

Public Investment in Food Infrastructure

Attracting full-service grocery stores is a challenge in the county, and numerous county grocery stores do not carry healthy foods. The UG is putting considerable effort into improving the food-retail environment in the city’s downtown area. The UG, through public-private financing initiatives, has supported the development of six new full-service grocery stores built in underserved neighborhoods. The UG created community-improvement districts (CID) and introduced a sales-tax levy to finance the development of these six full-service grocery stores.[lxiv]

In addition, the UG is leading a redevelopment plan for downtown KCK, called Healthy Campus Wyandotte, which includes, among other goals, improved access to healthy foods. The plan proposes the development of a full-service grocery store and a permanent space for a farmers’ market. The plan also aspires to promote urban agriculture by easing the process to access vacant lands in the downtown core.[lxv] The UG has committed $6 million in public funds and is raising another $4 million for the redevelopment effort.[lxvi]

Water Access

The UG of Wyandotte County and Kansas City has responded to growers’ water needs by dedicating public funds to improve access to water. The UG’s Department of Public Works and the Board of Public Utilities, an independent public utility in the county, have partnered to launch the H20 to Grow grant program to pay for up-front costs for water connections for individuals and organizations seeking to grow and produce and to reduce water runoff. In its most recent grant cycle (in 2015), the program offered $8000 to applicants. Since the program’s inception (in 2013), about $50,000 of the Department of Public Works budget have been appropriated for the program, and at least nine gardens have received new water connections.[lxvii]

Ideas for the Future

Wyandotte County is an ideal setting for promoting community food security by strengthening the viability of small- and medium-sized growers in the city and the larger region. The county has an extensive network of engaged and invested private individuals and civic organizations working to strengthen particular sectors within the county’s food system.[lxviii] Although local government leaders champion and support community-based work, strategic and purposeful local government action can amplify this food-systems activity across multiple sectors of the food system. Reducing bottlenecks in the food system, shortening supply chains, and clustering food-systems businesses can provide considerable public-health and economic returns to Wyandotte. Key ideas are outlined below.

Develop a Comprehensive Plan to Strengthen the County’s Food System

Although Wyandotte County faces significant challenges within its agriculture and food system, the county is home to a remarkable number of public, civic, and private initiatives to strengthen different sectors within the food system. Many of these efforts lack inter-sectoral coordination. The county’s Master Plan, which could offer a basis for such coordinated inter-sectoral activities, is largely silent about the food system.[lxix] Adopted in 2008 by county lawmakers, the plan addresses concerns about the future of land use, park and open space, transportation, environmental conditions, and urban design. Importantly, the plan serves as a comprehensive public-policy document to guide future development, public investments, and regulatory actions––many of which impact and are impacted by the food system.[lxx] Given the entrepreneurial and civic energy in the food system, this is the right time for the UG of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas to consider a special-purpose plan focused on food.

A Community Food-System Plan would serve as an addendum (or amendment) to the Master Plan to strengthen the county’s food system and to advance the goals of the Master Plan.[lxxi] Like the Master Plan, the proposed UG Community Food-Systems plan would provide a comprehensive and cohesive basis for future UG policy actions. These public actions could include, but are not limited to, the passage of regulations and ordinances, adoption of public-finance mechanisms, development of physical infrastructure, and establishment of governance and staffing structures that promote agricultural viability and expand food access. Precedents for these policy actions exist nationally and can be adapted for Wyandotte County, if appropriate.[lxxii] In particular, the experiences of the cities of Cleveland, OH and Minneapolis, MN may be of interest. Cleveland, like Wyandotte, had numerous grassroots initiatives that morphed into a more cohesive policy approach. Like Wyandotte, the city of Minneapolis, MN, in particular, had significant mayoral leadership that has advanced food-systems policy in large part due to concerns over public health. Examples of existing community food-systems plans are available in the searchable database.

Support Community Food Practices by Clarifying Local Laws for Residents and Food Stakeholders

Agriculture is a permitted use throughout the county’s residential districts. However, the zoning code offers an ambiguous definition of agriculture as applied to residential districts. For example, the code does not clarify whether agriculture is defined as backyard gardening, larger urban farms, or large-scale conventional agriculture. More important, even when the law is clear about the provisions for growing food, the language is not accessible to food stakeholders. Such lack of clarity results in confusion among residents and community food stakeholders. The UG staff and HCW can support agriculture and food-systems activity simply by including a definition of agriculture and food production and by providing short and concise fact sheets (one to two pages) explaining common UG food-related laws for residents. For example, fact sheets titled “Do you want to sell food that you raise on your private property?,” or “Do you want to raise chickens in your backyard?” could describe rules that a resident must comply with as well as a list of resources, such as contact information for the local extension agent.

Strengthen Agriculture and Food Production by Reducing Regulatory Barriers

Agriculture and food production can be strengthened in the county by reducing several regulatory barriers. For example, current zoning regulations limit the building of toolsheds on community gardens, which are essential to growing operations.[lxxiii] Additionally, there is ambiguity about allowing the on-site sale of produce grown on particular sites,[lxxiv] or the sale of produce on mobile markets in non-commercial sites. Modifying these regulations would make agricultural practices easier. Reducing regulatory barriers that impede local public institutions such as schools and colleges from purchasing local agricultural produce grown by conventional and urban farmers would also help to create market demand for both conventional and urban local agriculture. Ultimately, revising regulations in agriculture and non-agricultural zoning districts to be agriculture-friendly is essential to strengthening the food system.

Maximize Use of Healthy Food Retail by Providing Safe and Convenient Public Transit

To maximize the use of new food-retail environments in the county, including new grocery stores, the UG must ensure that the retail is accessible by safe, affordable, and convenient public transit. Food access could be improved by expanding bus routes and increasing the frequency of service to existing food retailers. Public transit is especially important for lower-income households that do not have access to automobiles. Interviewees also voiced a need for greater public safety, noting that if residents do not feel safe, no amount of investment in retail, whether that be new transit lines or new food retail within walking distance, will encourage them to use the retail.[lxxv]

Build a Stronger Regional Food System Through Intergovernmental Cooperation

Kansas City, KS is part of a bi-state metropolitan region that also includes Kansas City, MO (KCMO). This adjacency and layering of city and state boundaries contribute to a remarkable shared identity in the region. During conversations, residents talk about KCK and KCMO seamlessly. Despite this shared identity, Wyandotte County, and indeed Kansas City, has experienced greater disinvestment within the broader metropolitan region. Disparate policies (across state lines) also create regional inequity within an otherwise bustling metropolitan region. An important idea to consider is the possibility of developing and expanding shared service and revenue agreements among local governments, including across state lines, for functions related to the food system.[lxxvi] For example, two jurisdictions could develop an agreement to jointly fund the development of a physical storage or processing facility (funds could be generated through the sale of bonds), and a joint service agreement would ensure that the facility is available to both jurisdictions. The not-for-profit food sector in the metropolitan region is already demonstrating leadership by serving both Kansas and Missouri––the local governments, too, can experiment with such a possibility.

Use of Traditional Public Financing Tools to Strengthen Connections Across the Food System

As noted above, the Wyandotte County government has a history of using public-financing tools to promote economic development. Many of these public-financing tools lend themselves to strengthening economic connections across country growers and county residents, with stronger economic returns for the county. The UG has previously used Sales Revenue (STAR), Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts, and Neighborhood Revitalization Tax Rebate Incentives for various public purposes, to name a few. TIF, for example, could be used to establish the creation of a Food Innovation District, a cluster of food-related businesses located in close proximity that promote both economic and food-systems development, by sharing knowledge and infrastructure such as storage and distribution.

The Local Initiatives Support Corporation also serves Wyandotte County through reinvestment, particularly in housing and business development, with an emphasis on healthy communities. Many of the available economic and public finance tools are geared towards large-scale business development, and investing in small-scale business development may be especially helpful for regenerating the local food system. Purposeful application of fiscal tools to catalyze food-based economic development can go a long way to promote public health and sustain local growers.

Research Methods and Data Sources

Information in this brief comes from multiple sources. Quantitative data sources include the 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates and the 2012 US Census of Agriculture. Some spatial data on land use is estimated using the county’s parcel data and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Qualitative data include 14 in-depth interviews with representatives of various sectors of the food system as well as the UG of Wyandotte County and Kansas City policymakers and staff. The interviewees are not identified by name. Interviews were conducted from April to August, 2015. Qualitative analysis also included a review of policy and planning documents of the Unified Government and a review of the minutes of the Growing Food Connections steering-committee meetings. A draft of this brief was reviewed by interview respondents and community stakeholders prior to publication.

Acknowledgements

The GFC team is grateful to the Wyandotte GFC steering committee, Wyandotte County government officials and staff, Mid America Regional Council (MARC), and the interview respondents for generously giving their time and energy to this project. The authors thank colleagues at the Food Systems Planning and Healthy Communities Lab and the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo, Ohio State University, Cultivating Healthy Places, American Farmland Trust, and the American Planning Association for their support. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the 3E grant for Built Environment, Health Behaviors, and Health Outcomes from the University at Buffalo.

Recommended Citation

Raj, Subhashni and Samina Raja. “Growing a Local Food Economy for a Healthy Wyandotte.” In Exploring Stories of Opportunity. Edited by Samina Raja, 10 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project.

Notes

[i] “Eight ‘Communities of Opportunity’ Will Strengthen Links between Farmers and Consumers: Growing Food Connections Announces Communities from New Mexico to Maine,” Growing Food Connections, http://growingfoodconnections.org/news-item/eight-communities-of-opportunity-will-strengthen-links-between-farmers-and-consumers-growing-food-connections-announces-communities-from-new-mexico-to-maine/.

[ii] Caitlin Marquis and Julia Freedgood, “Wyandotte County, Kansas: Community Profile,” Growing Food Connections Project, growingfoodconnections.org/research/communities-of-opportunity.

[iii] The other three communities are Bonner Springs, Edwardsville, and Lake Quivira. Kansas Division of Emergency Management, “Region L Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan 2013 – 2018,” (2013).

[iv] United States Census Bureau, “Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 – County Census Summary File 1,” (2010).

[v] United States Census Bureau, “2014 Acs 5-Year Estimates,” (2014); Interview with Wyandotte County Cooperative Extension Representative (ID 86), July 02, 2015.

[vi] Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Wyandotte County (ID 94), June 11, 2015.

[vii] United States Census Bureau, “2014 Acs 5-Year Estimates.”

[viii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92), July 29, 2015; Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 99), June 12, 2015.

[ix] Bureau of Labor, “Unemployment Rate – Not Seasonally Adjusted,” (2015).

[x] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92); Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 98), June 12, 2015.

[xi] A food system is the interconnected, soil-to-soil network of activities and resources that facilitates the movement of food from farm to plate and back.

[xii] Perl Wilbur Morgan, History of Wyandotte County, Kansas: And Its People, vol. 2 (Lewis Publishing Company, 1911).

[xiii] Ronald V. Shaklee, Curtis J. Sorenson, and Charles E. Bussing, “Conversion of Agricultural Land in Wyandotte County, Kansas,” Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 1903 (1984).

[xiv] USDA, “2012 Census of Agriculture,” (2014). The number of farms does not include urban farms in the county. This number only reports traditional farms reported by the USDA. Unless otherwise specified, agricultural data in this and the next paragraph are from the USDA.

[xv] Based on estimates developed through a Geographic Information Systems analysis and interview with the Wyandotte County planning department.

[xvi] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92).

[xvii] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95), June 16, 2015.

[xviii] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 93), July 16, 2015; Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95).

[xix] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 93); Cultivate Kansas City, “Cultivate Kansas City: Growing Food, Farms and Communities for a Healthy Local Food System,” http://www.cultivatekc.org/.

[xx] “Cultivate Kansas City: Growing Food, Farms and Communities for a Healthy Local Food System”.

[xxi] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 93); Cultivate Kansas City, “Cultivate Kansas City: Growing Food, Farms and Communities for a Healthy Local Food System”.

[xxii] Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas, “New Roots for Refugees,” http://newrootsforrefugees.blogspot.com/p/about-us.html.

[xxiii] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95).

[xxiv] USDA, “2012 Census of Agriculture.”

[xxv] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 98); Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95); Interview with Representative of Food Aggregation Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 90), June 12, 2015, Wyandotte County, KS.

[xxvi] Fresh Farm HQ, “Fresh Farm Hq,” http://fresh-farm-hq.myshopify.com/.

[xxvii] Interview with Wyandotte County Cooperative Extension Representative (ID 86).

[xxviii] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95).

[xxix] Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Wyandotte County (ID 94).

[xxx] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92); Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95).

[xxxi] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95).

[xxxii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92).

[xxxiii] C. Gundersen et al., “Map the Meal Gap 2016: Overall Food Insecurity in Kansas by County in 2014.,” (Feeding America).

[xxxiv] Kansas Association of Community Action, “2012 Kansas Hunger Atlas: At the Intersection of Poverty and Potential,” (2012).

[xxxv] Bureau of Health Promotion, “Kansas Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System – Local Data, 2013,” (Kansas Department of Health and Environment, 2013).

[xxxvi] Mid-America Regional Council, “2015 Regional Health Assessment for Greater Kansas City,” (REACH Healthcare Foundation, 2015).

[xxxvii] Kansas Health Institute, “Kansas County Health Rankings 2009,” (2009).

[xxxviii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92); Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 89), August 05, 2015.

[xxxix] University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, “County Health Rankings 2016,” (2016).

[xl] Economic Research Service (ERS) and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), “Food Environment Atlas,” (2015).

[xli] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 89).

[xlii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 98); Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Wyandotte County (ID 97), June 11, 2015.

[xliii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 98).

[xliv] Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Wyandotte County (ID 97).

[xlv] Interview with Wyandotte County Cooperative Extension Representative (ID 86).

[xlvi] Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Wyandotte County (ID 87), June 12, 2015.

[xlvii] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 93).

[xlviii] Interview with Representative of Food Aggregation Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 90).

[xlix] The Double Up Heartland collaborative includes Cultivate Kansas City, Mid-America Regional Council, East West Gateway Council of Governments, Douglas County/City of Lawrence, Fair Food Network, and University of Kansas Medical Center. The grant will serve the KC Metro area and counties in Missouri.

[l] Cultivate Kansas City, “Cultivate Kansas City to Share in $5.8 Million Grant Giving Low-Income Families Access to Healthier Food Program to Reach 68 Farmers Markets; 117 Grocery Stores in Missouri and Kansas by 2019,” news release, 2016, http://evptrailmix.blogspot.com/2016/06/cultivate-kansas-city-press-release.html; Double Up Heartland, “Double up Food Bucks: A Win for Families, Farmers & Communities,” http://www.doubleupheartland.org/about/.

[li] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92).

[lii] Interview with Wyandotte County Cooperative Extension Representative (ID 86).

[liii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92).

[liv] Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, “Code of the Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, Kansas,” (2008).

[lv] The Unified Government consists of three branches: the executive (including the Chief Executive/Mayor and the county administrators), the legislative (including the Board of Commissioners, comprising ten representatives from each of its eight districts), and the judicial branch (including the municipal court and an ethics commission).

[lvi] State of Kansas, “Kansas Constitution,” in Article II, § 21 (1859).

[lvii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 92); Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, “Code of the Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, Kansas.”

[lviii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 99).

[lix] Healthy Communities Wyandotte, “Steps toward Health: Recommendations for a Better Future in Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas,” (Wyandotte, Kansas2012).

[lx] Roosters are not allowed. Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, “Code of the Unified Government of Wyandotte County/Kansas City, Kansas.”

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Farmers’ markets are a permissible accessory use (with an annual agreement) in the following districts: agricultural district (AG), limited business district (C-1), central business district (C-D), general business district (C-2), commercial district (C-3), light industrial and industrial-park district (M-1), general industrial district (M-2), heavy industrial district (M-3), and traditional neighborhood design (TND).

[lxiii] Districts requiring special-use permits include the following: rural residence (R), single family (R-1), two-family (R-2 and R-2 B), townhouse (R-3), apartment (R-5), high-rise apartment (R-6), mobile park (R-M), and non-retail business district (C-0). The special-use permit fee is $75.

[lxiv] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 89).

[lxv] Unified Government of Wyandotte County Planning and Zoning, “Downtown Parkway District: The Healthy Community Vision for Downtown Kansas City, Kansas,” (Wyandotte, KS2014).

[lxvi] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 96a), April 14, 2015.

[lxvii] Interview with Representative of Local or Regional Government in Wyandotte County (ID 89).

[lxviii] Food-system sectors include agriculture and food production, food aggregation, food wholesale, food processing, food retail, food acquisition, and management of food-related waste and excess food.

[lxix] Unified Government of Wyandotte County / Kansas City, “Unified Government of Wyandotte County / Kansas City, Kansas City-Wide Master Plan,” (Wyandotte, Kansas2008).

[lxx] Samina Raja, Branden Born, and Jessica Kozlowski Russell, A Planners Guide to Community and Regional Food Planning: Transforming Food Environments, Building Healthy Communities, 54 vols., Planning Advisory Service (Chicago, IL: American Planning Association, 2008).

[lxxi] The development of an effective food-systems plan is predicated on an inclusive public engagement process. The charge for such a planning process has been developed by the Wyandotte County Growing Food Connections Steering Committee, which developed a vision for the county’s food system in Spring 2015.

[lxxii] Zsuzsi Fodor and Kimberley Hodgson, “Healthy Food System in the Heartland: Intergovernmental Cooperation in the City of Lawrence and Douglas County, Kansas Advances Food Policy,” in Exploring Stories of Innovation, ed. Kimberley Hodgson and Samina Raja (Growing Food Connections Project, 2015); “Cleveland, Ohio: A Local Government’s Transition from an Urban Agriculture Focus to a Comprehensive Food Systems Policy Approach,” in Exploring Stories of Innovation, ed. Kimberley Hodgson and Samina Raja (Growing Food Connections Project, 2015); Kimberley Hodgson, “Advancing Local Food Policy in a Changing Political Climate: Cabarrus County, Nc,” ibid.; Kimberley Hodgson and Zsuzsi Fodor, “Mayoral Leadership Sparks Lasting Food Systems Policy Change in Minneapolis, Minnesota,” ibid.; “Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: A Mayor’s Office and Health Department Lead the Way in Municipal Food Policymaking,” in Exploring Stories of Innovation, ed. Kimberley Hodgson and Samina Raja (Growing Food Connections Project, 2016); Kimberley Hodgson, Zsuzsi Fodor, and Maryam Khojasteh, “Multi-Level Governmental Support Paves the Way for Local Food in Chittenden County, Vermont,” ibid. (2015); Jennifer Whittaker and Samina Raja, “How Food Policy Emerges: Research Suggests Community-Led Practice Shapes Policy,” in Translating Research for Policy Series (Growing Food Connections Project, June 2015); Elizabeth Whitton and Kimberley Hodgson, “Championing Food Systems Policy Change: City of Seattle, Wa,” in Exploring Stories of Innovation, ed. Kimberley Hodgson and Samina Raja (Growing Food Connections Project, 2015); “Lessons from an Agricultural Preservation Leader: Lancaster County, Pa,” in Exploring Stories of Innovation, ed. Kimberley Hodgson and Samina Raja (Growing Food Connections Project, 2015); Elizabeth Whitton, Jeanne Leccese, and Kimberley Hodgson, “A Food in All Policies Approach in a Post-Industrial City: Baltimore City, Md,” ibid.

[lxxiii] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 93).

[lxxiv] Interview with Representative of Agriculture Sector in Wyandotte County (ID 95).

[lxxv] Interview with Consumer Advocate Representative in Wyandotte County (ID 87).

[lxxvi] Examples of shared agreements across state lines are reported in Bristol, TN and Bristol, VA, for example. Other more well-known examples include the revenue-sharing agreement between the cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis in MN.

Community of Opportunity Feature

AUTHORS

Subhashni Raj, University at Buffalo Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

CONTRIBUTORS

Jill Clark, Ohio State University

Julia Freedgood, American Farmland Trust Kimberley Hodgson, Cultivating Healthy Places

SERIES EDITOR

Samina Raja, University at Buffalo

PROJECT COORDINATOR

Jeanne Leccese, University at Buffalo

DESIGN, PRODUCTION and MAPS

Samantha Bulkilvish, University at Buffalo Brenda Stynes, University at Buffalo Jennifer Whittaker, University at Buffalo

COPY EDITOR

Ashleigh Imus, Ithaca, New York

Recommended citation: Raj, Subhashni and SaminaRaja. “Growing a Local Food Economy for a Healthy Wyandotte.” In Exploring Stories of Oppor- tunity. Edited by Samina Raja, 10 pages. Buffalo: Growing Food Connections Project. Available on- line at: growingfoodconnections.org/publications/briefs/coo-community-profiles.